the I’oots, all indicate an affinity witli Cycadophyta. Broadly speaking, these results

hold good for the Medulloseae generally, though in the more elaborate Permian

species the differentiation of the steles among themselves, and certain peculiarities

of the secondary growth may render the likeness to Cycadean stems more stiiking.

On these anatomical grounds the Medulloseae were included by Potonié in

1897, in his happily named intermediate grouj) Cycadofilices.

The point on which the (piestion of the systematic position of the family

turned, was clearly that of the nature of the fructification. It had been suggested, some

years ago, on grounds of association and of common structural features, that seeds

of the genus Tr igo no ca r pon might probably prove to belong to species of Al e thopt

e r i s or Ne u r o p t

e r i s (W il d 1900). But

this remained nothing

more than a probable

suggestion, and it was

not till the close of 1903

that we received, from

my friend Mr. K id s t o n ,

tlie first definite proof

that a member of the

Nenropterideae was a

seedbearing plant.

Ml'. K id s t o n showed

that certain large seeds,

I'esembling a hazel-nut in

size and form, from the

Coal-Measures of Dudley

in England, ivere borne

on portions of a rachis

to which the characteristic

pinnules of the w'ell known

species, Ne u ro p t e r i s

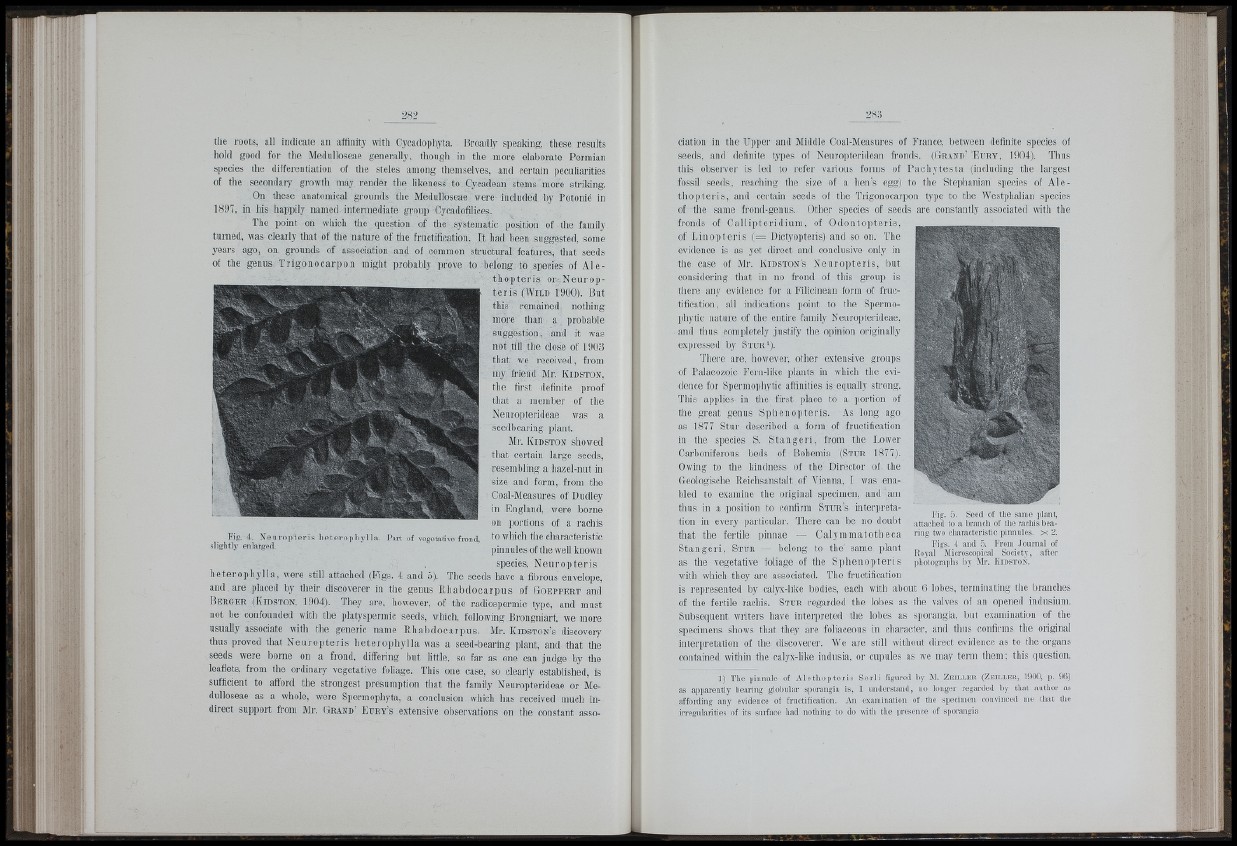

Fig. 4. N e u r o p t e r i s h e t e r o p h y l l a . Part of vegetative frond,

slightly enlarged.

h e t e r ophyl l a , were still attached (Figs. 4 and 5). The seeds have a fibrous envelope,

and are placed by their discoverer in the genus Rh a b d o c a rp u s of G o e p p e r t and

B e r g e r (K id s t o n , 1904). Tliey ai'e, however, of the radiospermic type, and must

not be confounded with the platyspermic seeds, which, following Brongniart, we more

usually associate witli the generic name Rhabdocarpus. Mr. K i d s t o n ’s discovery

thus proved that Neu ropt e r i s h e t e r ophy l l a was a seed-bearing plant, and that the

seeds were borne on a frond, differing but little, so far as one can judge by the

leaflets, from the ordinary vegetative foliage. This one case, so clearly established, is

sufficient to afford the strongest presumption that the family Nenropterideae or Medulloseae

as a whole, ivere Spermophyta, a conclusion which has received much indirect

support from Mr. G r a n d ’ E u r y ’s extensive observations on the constant asso-

elation in the Ujtper and Middle Coal-Measures of France, between definite species of

seeds, and definite types of Neurojiteridean fronds. (G r a n d ’ E u r y , 1904). Thus

this observer is led to refer vaiions forms of , Pachy t e s t a (including the largest

fossil seeds, reaching the size of a hen’s egg) to the Stejdianian species of Al e thop

t e r i s , and certain seeds of the Trigonocarpon type to the Westphalian species

of the same frond-genns. Other species of seeds are constantly associated with the

fi'onds of Cal l ip t e r i d i u m . of O d o n t o p t e r i s ,

of Lin op t e r is ( = Dictyopteris) and so on. The

evidence is as yet direct and conclusive only in

the case of Mr. K i d s t o n ’s Neu ropt e r i s , l)ut

considering that in no frond of this group is

there any evidence for a Eilicinean form of fructification,

all indications jioint to the Spermo-

l)liytic nature of the entire family Neiiroptei'ideae,

and thus completely justify the opinion originally

expi'essed by S t u r ').

There are, however, other extensive groiqis

of Palaeozoic Fern-like plants in which the evidence

tor Spermophytic affinities is equally strong.

This ajiplies in the first place to a ])ortion of

the great genus Spheno p te r i s . As long ago

as 1877 Stur described a form of fructification

in the species S. Stangei ' i , from the Lower

Carboniferous beds of Bohemia (S t u r 1877).

Owing to the kindness of the Director of the

Geologische Reichsanstalt of Vienna, I was enabled

to examine the oi'iginal specimen, and am

thus in a position to confirm S t u r ’s interpi'eta-

tion in every particular. There can be no doubt

Fig. 5. Seed of the same plant,

attached to a branch of the rachis hearing

that the fertile pinnae — Calymma t o t h e c a

two characteristic pinnules, x 2 .

S tang e ri , S t u r — belong to the' same ])lant

Figs. 4 and 5. From Journal of

iioyal Microscojiical Society, after

as the vegetative foliage of the S jihenop t e r i s

])hotogra])hs by Mr. Kidston.

with which they are associated. The fructification

is I'epresented by calyx-hke bodies, each with about (5 lobes, terminating the branches

of the fertile rachis. S t u r regarded the lobes as tlie valves of an opened indnsium.

Subsequent writers have intei-preted the lobes as sporangia, Imt examination of the

specimens shows that they are foliaceons in character, and thus confirms the original

interpretation of the discoverer. We are still without direct evidence as to the organs

contained wdthin the cal_yx-like indusia, or cuimles as we may term them; this question.

J) The pinnule of A l e t h o p t e r i s S e r l i figured by AL Ze ii.lkr (Zeii.ler, 1900, p. 96)

as apparently bearing globular sporangia is, I understand, no longer regarded by that author as

affording any evidence of fructification. An examination of tlie specimen convinced me that the

irregularities of its surface had nothing to do with tlie presence of siiorangia