Vi to

p : i

: l i

miglit be expected fi*om the inhabitants of tbe metropolis of Germany. The cause is to

be found in the want of commerce, and the consequent poverty of the middle classes.

In public matters, money is the soul of grief, as avcU £is of joy.

315. In Hungary, Hirsclifeld, in 1783, says, there were only the gardens of Esterhazy,

a seat of Prince Esterhazy, Avorthy of notice, and that they were chiefly indebted to the

beauty o fth e palace for their attractions. Dr. Toaatisou, in 1793, mentions Count Vetzy

as laying out his grounds in the English style, aided by a gardener Avho had been some

time iu England. The gai’dens of Count Esterhazy of Galantha, at Dotis, he considers

very fine ; and those of the Bishop of Erlau, at Eëlcho-Tiu’kan, as romantic. Dr. Bright

(Travels, 1815) mentions Kormond, the property of Prince Bathiani, as “ containing a

very handsome garden in the Fi-ench taste, Avith considerable hothouses and conservatories.”

Count BrunSAvick, of M aiton Vassar, had passed some time in England, and

his gai-dcn Avas laid out in the English style. The favourite mansion of Prince Esterhazy

is Eiscnstadt ; the palace has lately been improved, and the gardens, which were

laid out, in 1754, in the Ei’ench taste, were, in 1814, transforming into tho English

manner. (Travels in Hungary, p. 346.)

Division ii. Gardening, as an A r t o f Design and Taste, in Prussia.

316. The par/is and landscape-gardens o f Prussia ai’c situated chiefly in the neighbourhood

of Berlin ; and, lilvc those of Austria, are, for the most part, the property of

the king. Frederick II. accumulated immense wealth, and displayed it principally in

building and gardening, in Berlin, Potsdam, and their environs. Though the hmdscape-

gardcns in the Prussian dominions chiefly belong to the royal ñmiily, there arc still a ícav

belonging to private individuals deserving of notice, in the neighbom’hood of some of tho

principal toAvns. There are many in the neighbourhood of Dantzic ; some in tlie subm-bs

of Konigsbm-g, Mcmel, and Stettin. Hirschberg, a handsome toAvn in Silesia, has near

it sevcriS gardens. A gentleman in that neighbourhood has a garden, to the different

parts of which he has given poetical and mythological names. On the hill called the

Ilausberg many of the citizens have formed shady boAvers, and built pavilions Avith fireplaces

in them for tca-paities. The banks of the Oder, neai* Fi’ankfort, are, on one side,

bordered by small hills, upon Avhich, at short distances, are little summer-houses Avith

vineyards ; and in these, in suinincr, many of the inhabitants reside. (Adams’s Tour

through Silesia, 1800, 8a'0, 1804.)

317. The ancient gardens o f Sans Souci, at Potsdam, ai'e in the mixed style of SAvitzer,

Avith eveiy appendage and ornament of the French, Italian, and Dutch taste. Various

aitists, but chiefly Manger, a German ai’chitcct, and Salzmann, the royal gardener (each

of whom has published a voluminous description of his Avorks there), Avere employed in

their design and execution ; and a detailed topographical Iiistory of the Avhole, accompanied

by plans, elevations, and vicAvs, has been published by the late celebrated Nicolai,

of Berlin, at once an author, printer, bookbinder, and bookseller. Tbe gai-dens consist

of, 1. The hill, on the summit of Avhich Sans Souci is placed. The slope in front of

this palace is laid out in six ten-aces, each ten feet high, and its supporting Avail is

covered with glass, for peaches and A'iiies. 2. A hill to the east, devoted to hothouses,

culinary vegetables, and slopes or terraces for fruit trees. 3. A plain at the bottom of the

slope, laid out in SAvitzer’s manner, leading to the ncAv palace ; and, 4. A reserve of hothouses,

chiefly large orangeries, and pits for pines, to the west, near the celebrated Avind-

raill, of wliich Frederick could not get possession.

The Sans Souci scenci-y is more curious and varied than simple and grand. The hill of glazed terraces

crowned by Sans Souci'has, indeed, a singular appearance; but th e woods, cabinets, and innumerable

statues in the grounds below, are on too small a scale for the effect intended to be produced ; and, on the

whole, distract and divide the attention on the first view. Potsdam, with its environs, forms a crowded

scene of architectural and gardening efforts ; a sort of royal magazine, in which an immense number of

expensive articles, pillared scenery, screens of columns, empty palaces, churches, and public buildings,

as Eustace and Wilson observe, crowd on our eyes, and distract our attention. Hirschfeld, who does

not appear to have been a great admirer of Frederick,5and who, as the Prince de Ligne has remarked, was

touched with the Anglomania in gardening, says, in 1785, “ according to the last news from Prussia, the

tgste for gardens is not yet perfect in th a t country. A recent author vaunts a palace champêtre, which

presents as many windows as there are days in the year (f e - 77.): he praises the high hedges, mountains

of periwinkle, regular parterres of flowers, ponds, artificial grottoes, jots d ’eau, and designs traced on a

plain.” (Theorie, &c.,tom. v. p. 366.) Hodgskin,who visited Prussia in 1817, says, “ I merely looked at

the gardens, and th e outsides of th e palaces at Potsdam. Truly, the lodgings which are here provided

for one family m ight almost serve a nation. There arc not less than eight spacious palaces in Potsdam

and its vicinity belonging to the sovereign. I doubt if the profusion of the sovereigns of France, whatever

their splendour might be, ever equalled the profusion of the sovereigns of Prussia. The extensive

gardens of these palaces are ornamented with a number of statues and busts. Many of them are mutilated,

and most of them are covered with moss. T h e climates of Greece and Rome, from which countries

we have borrowed the custom of placing statues in gardens, were much more suitable to it than the

cold and wet climate of the North. The Greeks, and th e Romans, also, lived much more in th e open

air, in th eir public places, in their gardens, and amongst their statues, than we do or can. We live,

principally, in our houses ; and it is our houses, therefore, which we ought to render convenient, and to

adorn. Statues in our gardens accord neither Avith our climates, with our habits of life, nor with the

best mode of laying out our grounds. The great expense of so many carved pieces of marble is a mere

absurd imitation of an ancient custom ; it is unsanctioned by reason, and is equally condemned by good

taste and sage economy.” {Travels in Germany, vol. i. p. 76.) Bramsen, speaking of the same gardens

in 1818, says, “ they are very spacious, and tastefully laid out. Near the staircase of the pavilion of Sans

Souci are th e tombs of some of th e favourite dogs of Frederick II. The concert-room is adorned with

no less than ninety-six lamps, and vases in the shape of pine-apples. T h e kitchen represents a Roman

ruin. T h e grotto is elegant. The garden lies on the borders o fth e lake called theHeiligen See, and on

the banks of th e river Hovel. It commands an extensive prospect, and can boast of some very picturesque

scenery.” {L e tta s o f aPrussian Traveller, p. 51.) “ The charming and sylvan retreat of Sans Souci,”

says the courtly physician Granville, “ is approached through the Brandenburg Gate. On a small hill,

disposed in terraces, stands the château, to which the ascent is by a flight of steps, with quickset hedges on

eacn side. T h e terraces, and the well-arranged shrubberies, by the side of the palace, are ornamented

with flowers and fru it trees, vases and busts. At the foot of the hill, the gardens are decorated with

single statues and groups of figures in marble, and with two large marble reservoirs of water. A little

to the right of the pavilion a handsome edifice, containing a gallery of pictures, forms, together with the

principal buildings, an exceedingly pleasing landscape, which we viewed with pleasure from the western

extremity of Potsdam.” {Granville's Travels, Sec., vol. i. p. 266.)

318. The principal examples o f the English style in Prussia are tlie royal gai'dens at the

summer residence of Chai-lottenbnrg, near Berlin, begun by Frederick the Great, bnt

cliiefly laid out during tlie reign of Fi-ederick William II. They are not extensive, and

ai-e situated on a dull sandy flat, Avashed by tbe Spree ; under Avhicb unfavourable circumstances

it would be Avoudcrful if they were very attractive. In one p ait of these

gardens, a Doric mausoleum of great beauty contains the ashes of tbe much-lamented

queen. A dark avenue of Scotch pines leads to a cfrcle of tbe same frees, 150 feet in

diameter. Interior cfrcles are formed of cypresses and Aveeping-willoAvs ; and Avithin

these is a border of white roses and white lilies (Xilium candidum X.). The foi-m of

tbe mausolcimi is oblong, and its end projects from this interior circle, dfrectly opposite

the covered avenue. A few steps descend from the entrance to a platfoi-m, upon which,

on a sarcophagus, is a reclining figure of the queen ; a stab- at one side leads to the door

of a vault containing her remains.

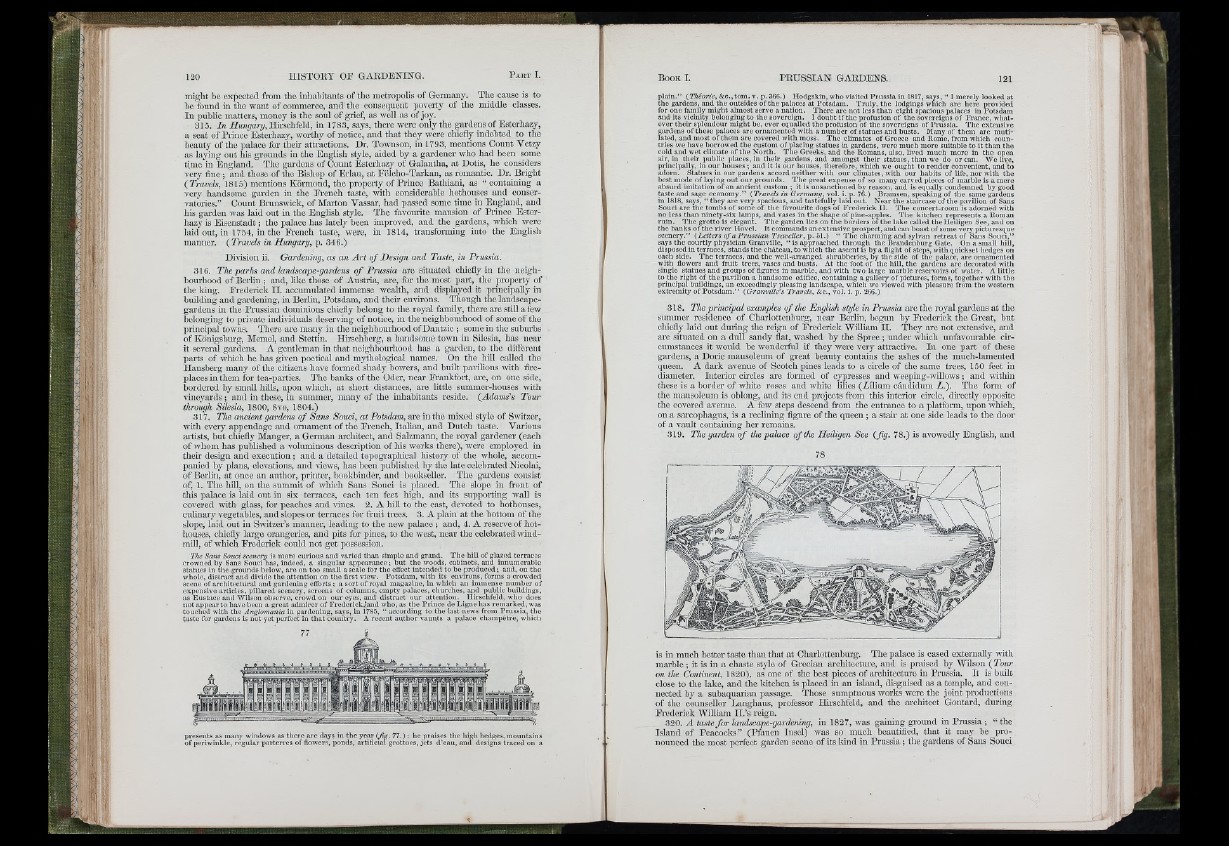

319. The garden o f the palace ofthe Heiligen See ( fg . 78.) is avoAvedly English, and

is in much better taste than that at Chariottenbiirg. The palace is cased externally Avith

ma rble; it is in a chaste style of Grecian ai-chitccture, and is praised by Wilson ( Tour

on the Continent, 1820), as one of the best pieces of architecture in Prassia. It is built

close to the lake, and the kitchen is placed in an island, disguised as a temple, and connected

by a subaquarian passage. Those sumptuous works Avere tlic joint productions

of the counsellor Langhaus, professor Hh-schfeld, and the architect Gontard, during

Fi'ederick William II.’s reign.

320. A taste fo r landscape-gardening, in 1827, Avas gaining gi-oimd in Prussia ; “ the

Island of Peacocks” (Pfauen Insel) was so much beautified, that it may be pronounced

the most perfect garden scene of its kind in P ru ssia ; the gardens of Sans Souci