r ,w ,

leaves, and a kind of spurious camphor from the roots. Cordiner describes the cinnamon

groves as delightful. “ Nothing can exceed the liixuiy of riding through them

in the cool hours of the morning, when the air is cool, and the sweetness ol' tho spring is

blended with the glow of summer. Every plant in the garden is at all times clothed with

fresh and lively g re en ; and, when tho cinnamon laurels put forth tlieir flame-colonrcd

leaves and delicate blossoms, the scenery is exquisitely beautiful. The fragrance, liowevcr,

is not so powerful as strangers arc apt to imagine. The cinnamon bark affords no scent

when the trees arc growing in tranquillity; and it is only in a few places that the air is perfumed

with the delicious odour of other slirubs, the greater proportion o fth e flowers and

blossoms of India being entirely destitute of that quality. Gentle undulations in the

ground, and clumps of majestic trees, add to the picturesque appearance of the scene ;

and a person cannot move twenty yards into a grove without meeting a hundred species

of beautiful plaiits and flowers springing up spontaneously. Several roads for can-iages

make winding circuits in the woods, and numerous intersecting footpaths penetrate tho

deepest thickets. In sauntering amidst these groves, a botanist or a simiilc lover of

nature may experience tlic most supreme delight whicli the vegetable creation is capable

ot affording; and tho zoologist will not be less gratified by the vai-icty, the number, and

the strangeness of many of the animal kingdom.” (Account o f Ceylon, vol. ii. p. 387.)

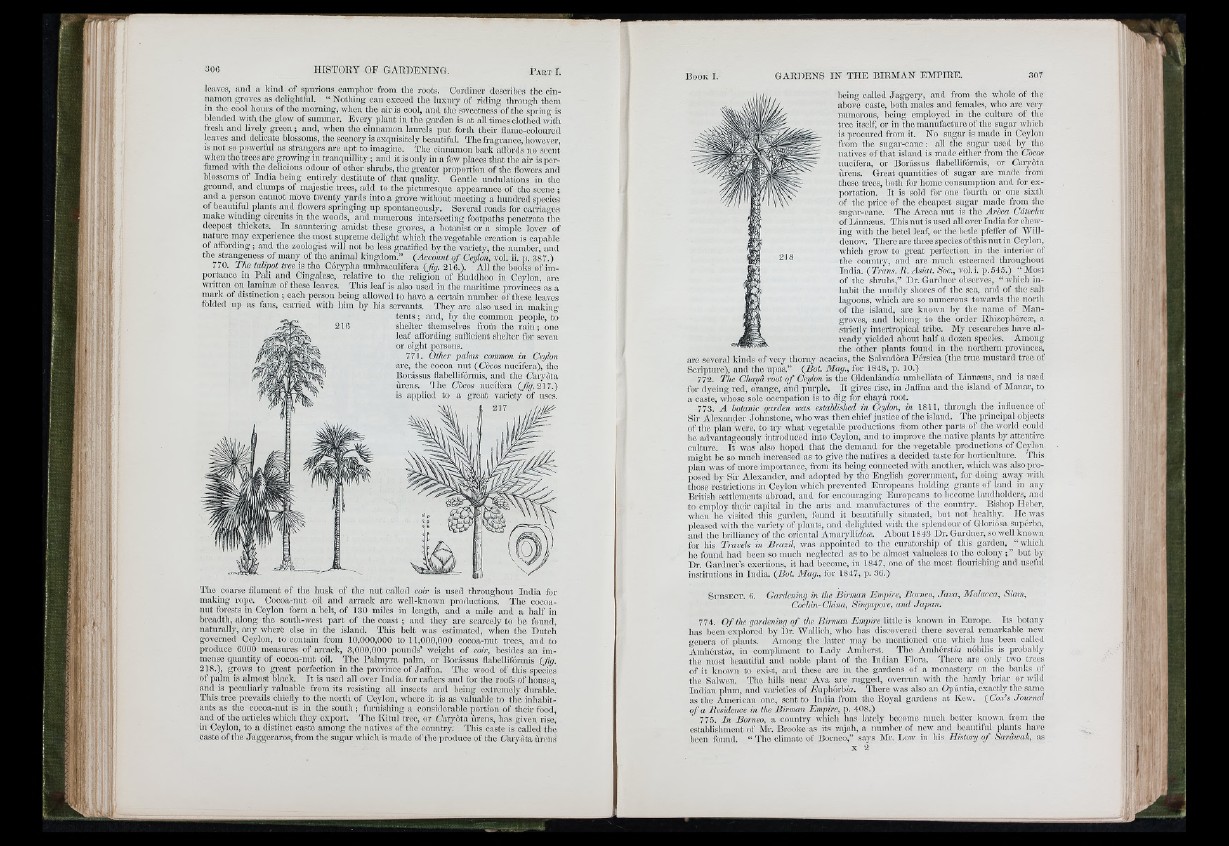

770. The talipot tt'ee is the Coi-ypha umbracidifera (jig. 216.). All tho books of importance

iu Pali and Cingalese, relative to the religion of Biiddhoo in Ceylon, arc

written on lamiinc of these leaves. This leaf is also used in the maritime provinces as a

mark of distinction ; each person hcing allowed to have a certain number of these leaves

folded up as fans, carried with liim by liis servants. They are also used in making

te n ts ; and, by the common people, to

shelter themselves from the r a in ; one

leaf affording sufficient slicltcr for seven

or eight persons.

771. Other palms common in Ceylon

arc, the cocoa nut (Cocos nucífera), the

Borássus liabclliformis, and the Caiybta

urcns. 'Ihc Cocos nucífera (//^. 217.)

is applied to a great variety of uses.

217

The coarse filament of the husk of the nut called coir is used tliroughout India for

making rope. Cocoa-nut oil and arrack arc well-known productions. The cocoa-

nut fdi-csts in Ceylon form a belt, of 130 miles in length, and a mile and a half in

breadth, along the south-west part of the coast ; and they are scarcely to be found,

naturally, any whcrb else in the island. This belt was estimated, when the Dutch

governed Ceylon, to contain from 10,000,000 to 11,000,000 cocoa-nut trees, and to

produce 6000 measures of an-ack, 3,000,000 pounds’ weight of coir, besides an immense

quantity of cocoa-nut oil. The Palmyra palm, or Bonissus flabclliformis (fig.

218.), gi-ows to great perfection in the province of Jaffna. Tlic wood of this species

of palm is almost black. It is used all over India for rafters and for the roofs of houses,

and is peculiarly valuiiblc from its resisting all insects and being extremely dnrable.

This tree prevails chiefly to the north of Ceylon, where it is as valuable to the inhabitants

as the cocoa-nut is in the south ; furnishing a consitlerable portion of thcir food,

aud of the articles which they export. 'Ih e Kitul tree, or Caryota ùrens, has given rise,

in Ceylon, to a distinct caste among the natives of the country. This caste is called the

caste o fth e Jaggcrai-os, from the sugar which is made of the produce of the Caryota lirciis

licing called Jaggery, and from the wliolc of the

above caste, both males and females, who arc very

numerous, being employed in the culture of tlic

tree itself, or in the manufacture of tho sugar whiclj

is procured from it. No sugar is made in Ceylon

from the vSugar-canc : all the sugar used by the

natives of that island is made cither from the Cocos

nucífera, or Borássus flabcllifói-mis, or Cnryòta

ùrens. Great quantities of sugar arc made from

these trees, both for home consumption and for exportation.

It is sold for one fourth or one sixth

of the price of the cheapest sugar made from the

sugar-cane. The Areca nut is the Areca Catechu

ofifinnauis. 'J'hisnutisuscd all over India for chewing

with the betel leaf, or the lietle pfcffer of Willdenow.

There arc three species ofthisnut in Ceylon,

which grow to gi-eat perfection in the interior of

the country, and are much esteemed throiighont

India. (Ira n s. Ji. Asial. Soc., vol.i. p..545.) “ Most

of the shrubs,” Dr. Gardner observes, “ wliich inhabit

the muddy sliorcs of the sea, and of the salt

lagoons, which are so numerous towards the nortli

of the island, are known by the name of Mangroves,

and belong to the order Rhizopliôrcoe, a

strictly intertropical tribe. My researches have already

yielded about half a dozen species. Among

the other plants found in the northern provinces,

are several kinds of very thorny acacias, the Salvadora Pérsica (the true mustard tree of

Scripture), and the upas.” (Bot. Mag., for 1848, p. 10.)

772. The Chaya rout o f Ceylon is the OldenhmdM umbellata of Linnæus, and is used

for dyeing red, orange, and purple. I t gives rise, in Jaffna and the island of Manar, to

a caste, whose sole occupation is to dig for chaya root.

773. A botanic garden was established in Ceylon, in 1811, through the influence of

Sir Alexander Johnstone, who was then chief justice of the island. TJic principal objects

of the plan were, to try what vegetable productions from other parts of the world could

be advantageously iiitrodnccd into Ceylon, and to improve the native plants by attentive

culture. It was also hoped tliat tlic demand for the vegetable productions of Ceylon

might be so much increased as to give the natives a decided taste for liorticnltnrc. 'Phis

plan was of more importance, from its being connected with another, whicli was also pru-

])Oscd by Sir Alexander, and adopted by the English govcrmncnt, for doing away with

those restrictions in Ceylon which prevented Europeans holding gi-ants of land in any

British settlements abroad, and for encouraging Europeans to become landholders, and

to employ thcir capital in the arts and maiiufacturcs of the country. Bishop Jlcbcr,

when lie visited this garden, found it beautifully situated, but not healthy. He was

pleased with the variety of plants, and delighted with the splendour of Gloriósa supèrba,

and the brilliancy of the oriental Amaryllide«. About 1843 Dr. Gardner, so well known

for his Travels in Brazd, was appointed to the curatorship of this garden, “ which

lie found had been so much neglected as to be almost i-aluclcss to the colony ; ” but by

Dr. Gardner’s exertions, it had become, in 1847, one of the most flourishing and useful

institutions in India, (¡dot. Mag., for 1847, p. 36.)

S u b s e c t . G. Gardening in the Birman Empire, Borneo, Java, Malacca, Siam,

Cochin-China, Singapore, and Japan.

774. O f the gardming o f the. Birman Empire YxìWqxs known in Europe. Its botany

has ])oen'explored by Dr. Wallich, who has discovered there several remarkable new

gciiei-a of ])lants. Among the latter may be mentioned one which has been called

Anilicrst/n, in compliment to Lady Amherst. The Amliérstía nóbilis is probably

tlic most beautil'ui aud noble iilant of the Indian Flora. There arc only two trees

of it known to exist, and these arc iu the gardens of a monastery on the banks of

the Salwcn. The hills near Ava are rugged, overrun ivitli the hardy briar or wild

Indian plum, and varieties of FJuphórbá?. There was also an Opiintia, exactly the same

as the American one, sent to India fr-om the Royal gardens at Kew. (CoFs Journal

o f a licsidence in the Birman Empire, p. 408.)

177). In Borneo, a country which has lately become much better known from the

establisliment of Mr. Brooke as its rajah, a number of new and beautiful plants liavc

been found. “ The climate of Borneo,” says Mr. Low in Ids History o f Saniwak, as