r rV]

contraiy, exhibits the same vegetation on both shores ; and, 3. By long and lofty chains

of monntains. To these causes arc to be attributed the fact, that similar climates and

soils do not always produce similar plants. Thus in certain parts of North America,

which altogether resemble Europe in respect to sod, climate, and elevation, not a single

European plant is to be found. The same remark will apply to New Holland, the

Cape of Good Hope, Senegal, and other countries, as compared with countries in similar

}>hysical circumstances, but geographically ditterent. The scpai-ation of Africa and

South America, Htunboldt considers, must have taken place before the developement of

organised beings, since scai'cely a single plant of the one country is to be found in a wild

state iu tlio other.

Sect. II. Physical Distribution o f Vegetables.

1089. The natural circumstances affecting the distribution of plants, may be considered

in respect to temperature, elevation, moisture, soil, and light.

1090. Temperature has the most obvious influence on vegetation. Every one knows

that the plants of hot countries cannot in general live in such as arc cold, and the contrary.

The wheat and barley of Europe wdl not grow within the tropics ; the same

remark applies to plants of still higher latitudes, such as those within the polar circles,

■which cannot be made to vegetate in warmer latitudes ; nor can the plants of hot

latitudes be made to vegetate in colder ones, without the aid of artificial heat. In

this respect, not only the medium temperature of a country ought to be studied, but the

temperature of different seasons, and especially of winter. Countries where it never

freezes ; those where it never freezes so strongly as to stagnate the sap in the stems of

plants ; and those where it freezes sufficiently to penetrate into the cellular tissue ; form

three classes of regions in wliich vegetation ought to differ. But this difference is somewhat

modified by the effect of vegetable structure, which resists, in different dcgi-ees,

the action of frost ; thus, in general, trees wliich lose their leaves during winter resist

the cold better than such as retain them ; resinous trees more easily than such as are

not so ; herbs of which the shoots arc annual and the root perennial, better than those

wliere the stems and leaves are persistent ; annuals which flower early, and whose seeds

drop and germinate before winter, resist cold less easily than such as flower late, and

whose seeds lie doimant in the soil till spring. Monocotyledonous trees, which have

generally persistent leaves and a tinink without bark, as in palms, are less adapted to

resist cold than dicotyledonous trees, which are more favourably organised for this purpose,

not only by the natiu-c of their proper juice, but by the disposition of the cortical

and alburnous layers, and the habitual carbonisation of the outer bark. Plants of a diy

nature resist cold better than such as are watery; all plants resist cold better in diy

winters than in moist winters ; and an attack of frost always does most injury in a

moist country, in a humid season, or when the plant is too copiously supplied with water.

Hence, after warm dry summers, when plants have ripened tlieir wood properly and the

watery particles have evaporated, exotic trees and shrubs will bear a much gi-eater degree

of frost than they can do after cold moist summers, during which the wood has not

ripened.

Sortie plants of firm texture, but n a tiv e s o f w a rm c lim a te s , w ill en d u r e a fr o s t o f a f e w h ours) c ontinuance,

as th e orange a t Genoa {.Humboldt, D e Distrib u tio n o F la n ta r um ) ; and the same thing is said of the palm

and pine-apple, facts most important for th e gardener. Elants of delicate texture, and natives of warm

climates, are destroyed by the slightest attack of frost, as th e Phasòolus, Tropas'olum, Pelargònium,

Dàhh'o, &c.

T h e tem p e ra tu r e o/s/iring-has a material influence on the life of vegetables ; the injurious effects of late

frosts are known to every cultivator. In general, vegetation is favoured in cold countries by exposing

plants to the direct influence of the sun ; but this excitement is injurious in a country subject to frosts

late in the season : in such cases, it is better to retard than to accelerate vegetation.

The tem p e ra tu r e o f sum m e r , as it varies only by th e intensity of heat, is not productive of so many injurious

accidents as that of spring. Very hot dry summers, however, destroy m any delicate plants, and

especially those of cold climates. A very early summer is injurious to the germination and progress of

seeds; a short summer to their ripening, and a prolonged one on th e contrary.

A u tu m n is an important season for vegetation, as it respects th e ripening of seeds ; hence, where that

season is cold and humid, annual plants, which naturally flower late, are never abundant, as in tbe

polar regions ; the effect is less injurious to perennial plants, which generally flower earlier. Frosts

early in autumn are as injurious as those which happen late in spring. T h e conclusion, from these

considerations, obviously is, that temperate climates are more favourable to vegetation than such as are

either extremely cold or extremely hot. But th e warmer climates, as Keith observes, are more favour-

able upon th e whole to vegetation than th e colder, and that nearly in proportion to their distance from

th e equator. The same plants, however, will grow in the same degree of latitude, throughout all degrees

of longitude, and also in correspondent latitudes on different sides of the equator ; the same species of

plants, as some of the palms and others, being found in Japan, India, Arabia, the West Indies, and part

of South America, which are all in nearly th e same latitudes ; and th e same species being also found in

Kamschatka, Germany, Great Britain, and the coast of Labrador, which are all also in nearly th e same

latitudes. ( Willdenow, p. 374.)

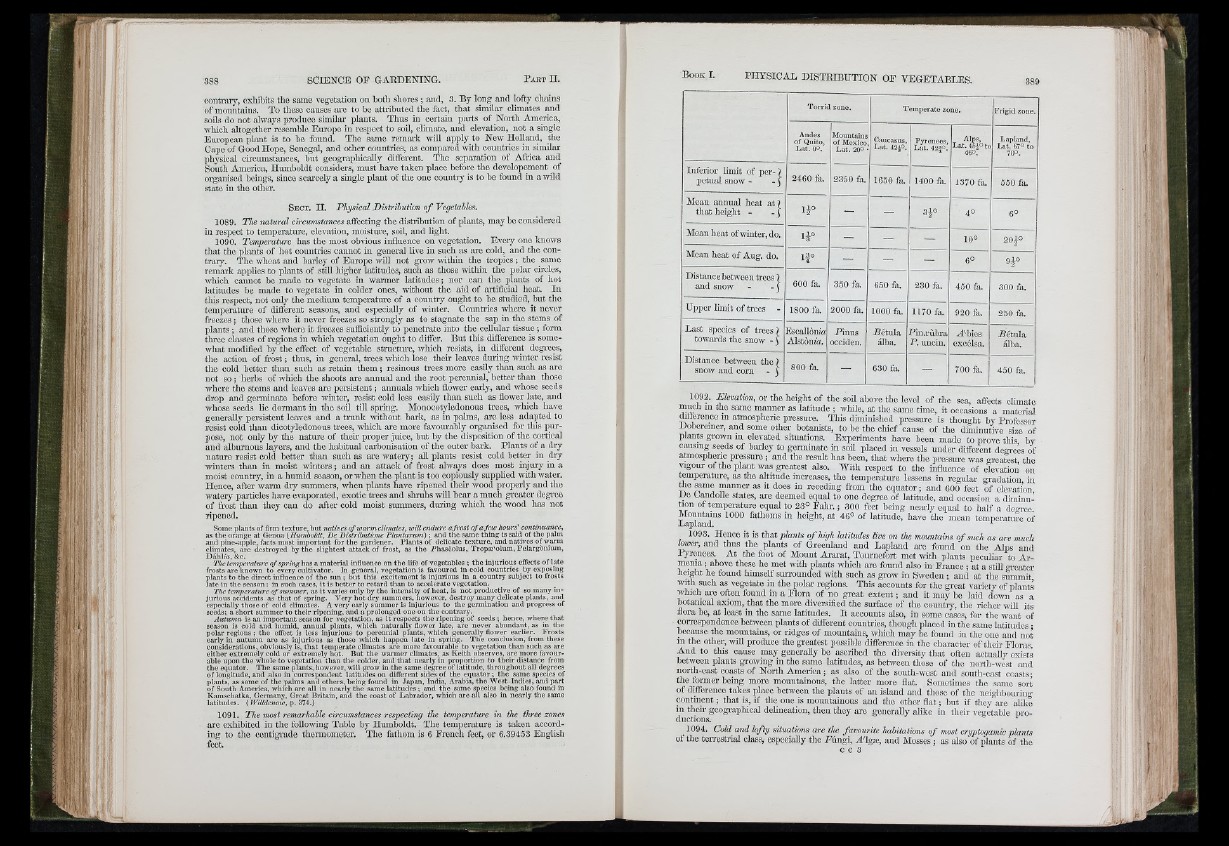

1091. The most remarkable circumstances respecting the temperature in the three zones

are exhibited in the following Table by Humboldt. The temperature is taken according

to the centigrade thermometer. The fathom is 6 French feet, or 6.39453 English

feet.

Torrid zone. Temperate zone. Frigid zone.

Andes

of Quito,

Lat. 0°.

Mountains

o f Mexico,

Lat. 20° •

Caucasus,

’ Lat. 42¿o.

Pyrenees,

Lat. 42|o.

Alps,

Lat. 45io to

460.

Lapland,

Lat. 67° to

700.

Inferior limit of p e r - )

pctual snow - - 1 2460 fii. 2350 fa. 1650 fii. 1400 fa. 1370 f a 550 fa.

Mean annual heat at ?

that height - - ^ — — 3^° 4° 6°

Mean h eat of winter, do. — — 10° 20^°

Mean heat of Aug. do. i | ° — — — 6° 9^°

Distance between tre es)

and snow - - J 600 fa. 350 fa. 650 fa. 230 fa 450 f a 300 f a

Upper limit of trees - 1800 fa. 2000 fa. 1000 fa. 1170 fa 920 fii. 250 f a

Last species of trees!

towards the snow - \

Escallonza

Alston/cc.

Pinus

occiden.

F é tu la

álba.

Pìn.rùbra

P. uiicin.

A'bics

excelsa.

F c tu la

álba.

Distance between th e )

snow and com - j 800 fa. — 630 fa — 700 fa 450 fa.

1092. Elevation, or the height of the soil above the level of the sea, affects climate

much in the same manner as latitude ; whüe, at the same time, it occasions a material

difierenco m atmospheric pressure. This diminished pressme is thought by Professor

Dobcrcmer, and some other botanists, to be the chief cause of the diminutive size of

plants grown m elevated situations. Experiments have been made to prove this by

causing seeds of barley to germinate in soü placed in vessels under different degi-ees of

atmospheric pressure; and the result has been, that where the pressure was oi-eatest the

vigour of the plant was greatest also. With respect to the influence of elevation on

tempcratui-e, as the altitude increases, the temperature lessens in regiüar gradation in

fric same manner as it does iu receding from the equa tor; and 600 feet of elevation

JJc Candolle states, are deemed equal to one degree of latitude, and occasion a diminution

of temperature equal to 23° F a h r .; 300 feet being ncai-ly equal to half a degree

L a p l f 1000 fathoms iu height, at 46° of latitude, liave tlie mean temperature of

1093. Hence it is that plants o f high latitudes Uve on the mountains o f such as are much

lower, and thus the plants of Greenland and Lapland are found on the Alps and

Pyrenees. A t the foot of Mount Ararat, Tournefort met with plants peculiar to A rmenia

; above these he met with plants which arc found also in F ran c e ; at a still gi-eater

height he found himself sun-ounded with such as grow in Sweden ; aud at the summit

with such as vegetate in the polar regions. This accounts for the great variety of plants

which arc often found in a Flora of no great ex ten t; and it may be laid down as a

botanical axiom, that the more diversified the surface of the country, the richer will its

flora be, at least in the same latitudes. I t accounts also, in some cases, for the want of

con-espondonce between plauts of different countries, though placed in the same latitudes •

because the mountains, or ridges of mountains, which may be found in the one and not

m the other, will produce the greatest possible difference in tlio character of thcir Floras

And to this cause may gencrafly be ascribed the diversity that often actuaUy cxist.s

between plants growing in the same latitudes, as between thoso of the north-west and

north-east coasts of North America; as also of the south-west and south-east coasts;

the former being more mountainous, the latter more flat. Sometimes the same sort

of difference takes place between the plants of an island and those of the neighbouring

continent; that is, if the one is mountainous aud the other fla t; but if they arc alike

in thcir geographical delineation, then they ai-e generally alike in their vegetable productions.

1094. Cold and lofty situations are the favourite habitations o f most crijptogamic plants

of the terrestrial class, especially the Fúngi, A'lgoe, and Mosses; as also of plants of the

C C 3