II

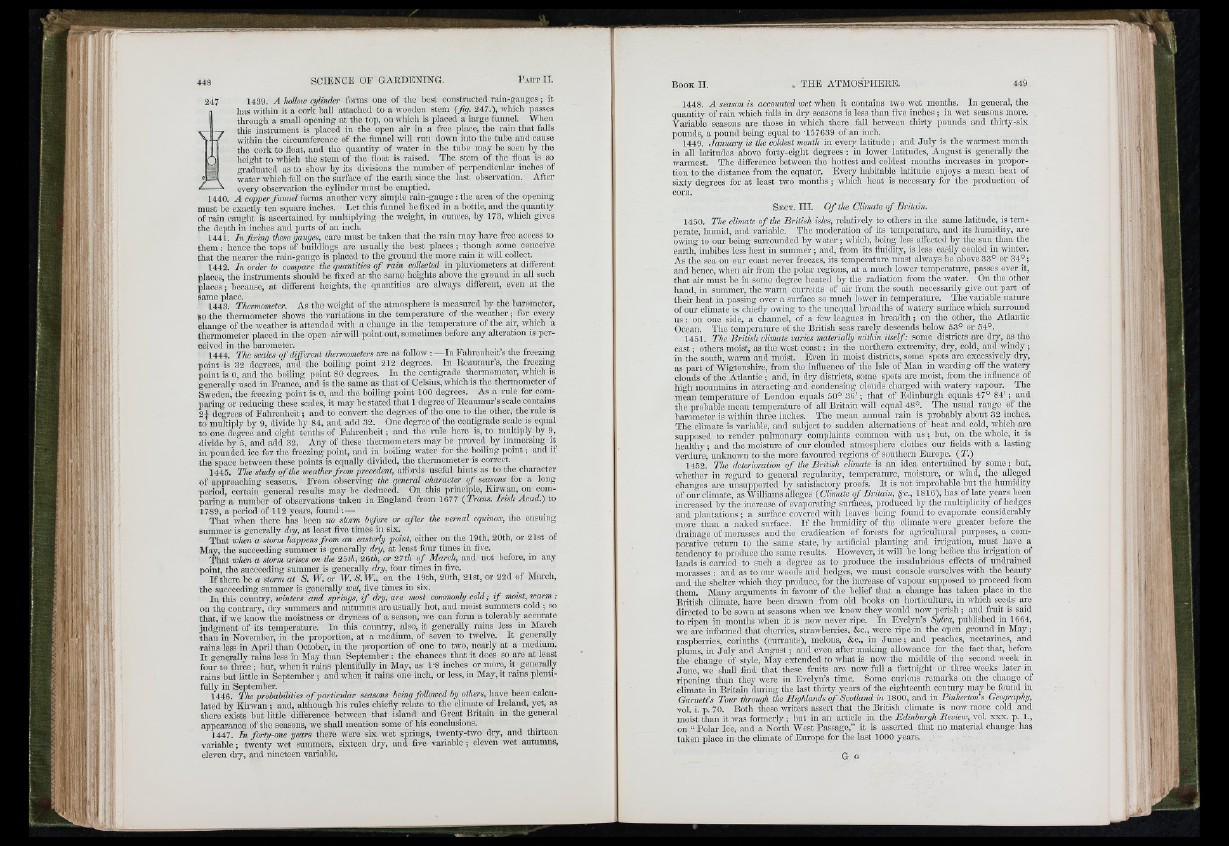

1439. A holbm cylinder fomis ouo of tlio best coustmcted rain-gaugos; it

has within it a cork ball attached to a wooden stem ( f y . 247.), which passes

through a smidi opening at tho top, on which is placed a large funnel. When

this instniment is placed in the open air in a free place, the rain that falls

within the circumference of the funnel will run down into the tube and cause

the cork to float, and tho quantity of water in the tube may be seen by tho

hci<ffit to which the stem of the float is raised. Tho stem of the float is so

graduated as to show by its divisions the number of perpendicular inches of

wator which fell on the surface of the earth since the last observation. After

every observation the cylinder must be emptied.

1440. A copper funnel forms another very simple rain-gauge : tho area of the opening

must be exactly ten square inches. Let this funnel be flxcd in a bottle, and tho quantity

of rain caught is ascortainod by multiplying tho weight, in ounces, by 173, which gives

the depth in inches and parts of an ineli.

1441. In fix in g these gauges, care must bo taken that the rain may have free access to

th em ; hence the tops of buildmgs are usually tho best places; though some concoivo

that the nearer the rain-gauge is placed to the ground the more rain it wiU collect.

1442. In crrder to compare the quantities o f rain collected in pluviometers at different

places, the instruments should be fixed at the same heights above the ground in all such

pla ces; because, at different heights, the quantities are always different, oven at tho

same place.

1443. Thermometer. As the weight of the atmosphere is measured by the barometer,

so tho thermometer shows the variations in tho temperature of the weather; for ovevy

change of the weather is attended with a change in the temperature of the air, which a

thermometer placed in the open air will point out, sometimes before any alteration is perceived

in tho bai'omotcr. . , , „

1444. The scales o f different thermometers m e as follow In Fahrenheit s the freezing

point is 32 dogi-ees, and tho boiling point 212 degrees. In Ecanmur’s, the freezing

point is 0, and tho boiling point 80 degrees. In the centigrade thermometer, wliich is

generally used in Franco, and is the samo as that of Celsius, which is the thermometer of

Sweden, the ft-oezing point is 0, and the boiling point 100 degrees. As a i-ulo for comparing

or reducing these scales, it may be stated that 1 degree of Ecaumiir’s scale contains

2 ) degrees of Falircnheit; and to convert tho degrees of the one to the other, the rule is

to multiply by 9, divide by 84, and add 32. Ono degree of the centigrade scale is equal

to one degree and eight tenths of Fah ren h eit; and the n d e here is, to multiply by 9,

divide by 6, and add 32. Any of these thermometers may he proved by immersing it

in pounded ice for the freezing point, and in boilmg water for tho boiling p o in t; and if

the space between these points is equally divided, the thermometer is correct,

1445. The study ofthe weather from precedent, affords useful hints as to the clnu'actcr

of approaching seasons. From observing the general character e>f seasons for a long

period, certain general results may bo deduced On this principle, Kirwan, on comparing

a number of observations taken in England from 1677 (Trans. Irish Acad.) to

1789, a period of 112 years, found : —

That when there has been no storm hefare or after the vernal equinox, tho ensuing

summer is gencraUy dry, at least five times in six.

That when a storm happens from an easterly point, either on the 19th, 20th, or 21st of

May, the succeeding summer is generally dry, at least four times in five.

That when a storm arises on the 25th, 26th, or 21th o f March, and not before, in any

point, the succeeding summer is generally dry, four tinie.s in five.

I f there be a storm at S. W. or W. N. IF., on the 19th, 20th, 21st, or 22d of March,

the succeeding summer is generaUy wet, five times in six.

In this countiy, winters and springs, i f diy, are most cammmily cold; i f moist, warm ;

on the contrary, dry summers and autumns are usually hot, and moist summers cold ; so

that, if we know the moistness or dryness of a season, we can form a tolerably accurate

judgment of its temperature. In tliis country, also, it generally rains less in March

than in November, in the proportion, at a medium, of seven to twelve. It generally

rains less in April than October, in the proportion of one to two, nearly at a medium.

I t generaUy rains less in May than September : the chances that it does so are at least

four to three ; but, when it rains plentifully in May, as 1-8 inches or more, it generally

rains but little in September ; and when it rains one inch, or less, in May, it rains plonti-

fnlly in September. , . , , ,

1446. The probalilities o f particular seasons being followed by others, have heen ealanlated

by Kinvan ; and, although his rules cliiefly relate to the climate of Ireland, yet, as

there exists but little difference between that island and Great Britain in the general

appearance of the seasons, we shall mention some of his conclusions.

1447. In forty-one years there were six wet springs, twenty-two dry, and thirteen

variable; twenty wet summers, sixteen dry, and five variable; cloven wet autumns,

eleven diy, and nineteen variable.

. T IIE ATMOSP IIEEE.

1448. A season is accounted wet when it contains two wet months. In general, the

quantity of rain which falls iu dry seasons is less than five inches ; in wet seasons more. .

Variable seasons are those in which there fall between thirty pounds and thirty-six

pounds, a pound being equid to '157639 of an inch.

1449. .lanuary is the coldest month in every latitude ; and Ju ly is the wannest month

in all latitudes above forty-eight degrees : in lower latitudes, August is generally the

warmest. The difference between the hottest and coldest months increases in proportion

to the distance from the equator. Every habitable latitude enjoys a mean heat of

sixty degrees for at least two months ; which heat is necessary for the production of

corn.

Sect. III. O f the Climate o f Britain.

1450. The climate ofthe British isles, relatively to others in tho samo latitude, is temperate,

liiiinid, and variable. The moderation of its temperature, and its humidity, are

owing to our being suiToundcd by w a te r; which, being less affected by the sun than the

earth, imbibes less heat in summer ; and, from its fluidity, is less easily cooled in winter.

As the sea on our coast never freezes, its temperature must always he above 33° or 34°;.

and hcncc, when air from the polar regions, at a much lower temperature, passes over it,

that air must be in some degi'cc heated by the radiation from the water. On the other

hand, in summer, the wann cuiTonts of air from the south nccessai-ily give out part of

their heat in passing over a surface so much lower in temperature. The variable natui-e

of our climate is chiefly owing to the unequal breadths of wateiy surface whicli surround

u s : on ono side, a channel, of a few leagues in b re ad th ; on the other, the Atlantic

Ocean. The temperature of the British seas rarely descends below 53° or 54°.

1451. The British climate varies materially within itself: some districts are diy, as the

o a st; others moist, as the west co a st; in tho northern extremity, dry, cold, and windy ;

in the south, warm and moist. Even in moist districts, some spots are exeessivcly diy,

as part of Wigtonshfre, from the influence of tho Isle of Man in warding off tho wateiy

clouds of tho A tlan tic ; and, in diy districts, some spots are moist, from the influence of

high mountains in attracting and condensing clouds charged with wateiy vapour. The

mean tcmpcratiuo of London equals 60° 3 6 '; that of Edinburgh equals 47° 8 4 '; and

the probable mean temperatm'c of all Britain will equal 48°. The usual range of the

barometer is within three inches. The mean annual rain is probably about 32 inches.

Tho climate is variable, and subject to sudden alternations of heat and cold, which are

supposed to render pulmonary complaints common with u s ; but, on the whole, it is

h ea lthy; and the moisture of our clouded atmosphere clothes our fields with a lasting

verdure, unknown to the more favoured regions of southern Eiu-ope. (T .)

1462. The deterioration o f the British climate is an idea entertained by some; but,

whether hi regard to general regularity, temperature, moisture, or wind, the alleged

changes arc unsupported hy satisfactoiy proofs. I t is not improbable but the humidity

of our climate, as Williams alleges (Climate o f Britain, §•«, 1816), has of late years been

increased hy the increase of evaporating surfaces, produced hy the imiltiphcity of hedges

and plantations; a surface covered with leaves being found to evaporate considerably

more than a naked surfiice. I f the humidity of tho climate were greater before the

drainage of morasses and the eradication of forests for agi-icultural puiqioses, a comparative

rctui-n to the same state, by artificial planting and in'igation, must have a

tendency to produce tho same results. However, it will be long before the in'igation of

lands is can-iod to such a degree as to produce the iiisalubi-ious effects of undrained

morasses : and as to our woods and hedges, we must console ourselves with the beauty

and the shelter which they produce, for the increase of vapour supposed to proceed from

them. Many arguments in favour of tho belief that a change has taken place in tho

British climate, have been drawn from old books on horticultxu-e, in which seeds are

directed to be sown at seasons when we know they would now perish ; and frait is said

to ripen in months when it is now never ripe. In Evelyn’s Ni/fco, published in 1664,

wo are infoi-mcd that chen-ies, strawbei-ries, &c., were ripe in the open gi-ound in M a y ;

raspberries, corinths (cun-ants), melons, &c., in J u n e ; aud peaches, ncctai-ines, and

plums, in Ju ly and A u g u st; and oven after making allowance for the fact that, before

the change of stylo. May extended to what is now the middle of the second week in

June, we shaU find that these fraits are now full a fortnight or three weeks later in

ripening than they were in Evelyn’s time. Some curious remarks on the change of

climate in Britain during the last thirty years of the eighteenth century may be found in

Gametes Tour through the Highlands o f Scotland in 1800, and in Pinherton’s Geography,

vol. i. p. 70. Both these writers assert that the British climate is now more cold and

moist than it was formerly; but in an article in the Edinburgh Iteview, vol. xxx. p. 1.,

on “ Polar Ice, and a North West Passage,” it is asserted that no material change has

taken place in the climate of Europe for the last 1000 years.

G G