I i

lii '

i

|. J

. 'N' 'i,

which vary from 15 in. to 18 in. asunder throughout their whole length, but become more

frcducnt at the farther end, which is closed. The general direction of the holes is upwards

except some few in the bottom, to keep the pipe clear of condensed water. The

case being built inclining towards the most convenient spot for draining, the condensed

water is taken away by a small siphon, about 3 or 4 in. deep, shown in fig . 6-29. A

steam-pipe of 1 in. diameter is sufficient for a case of 50 ft. in length ; and, it proper

attention be paid to the dimensions and distance of the holes, which in tins case need

not be above ono sixth closer at the farther end than at the commencement, scarcely the

least difference of temperature will be perceptible at each end of the case ; an effect

utterly unattainable in the best constructed firc-iiuc, which, in appearance, it so much

resembles. Thcro is, however, no particular proportion of the height to the breadtli ;

that depending entirely on convenience. Where freestone cases are used, it is tound

necessary that they should receive two or three coats of linseed oil, to prevent the escape

of steam through them. It is better to give moisture to the house by steam-cocks

fixed at the top of the cases, as shown in fig . 629.; humidity can then he regulated at

[ilcasurc.

S u b s e c t . 8. H e a tin g by H o t W a te r.

2133. T he a r t o f heating by hot w ater, which is now most generally^ practised in hothouses,

was invented in Paris in 1777, by M. Bonncmain ; and it was first made publicly

known in this country by Count Chabannes, iu 1815. The first hothouse heated by

hot water appears to have been one at Sundridge Park, Kent, which was heated by

Count Chabannes, in 1816. In 1818, a pamphlet was published by this gentleman, in

which he describes what he calls a “ new water calorifère,” and its application to various

punioscs in domestic economy and horticulture. Notwithstanding the undoubted fact,

that both a dwclling-hoiise and a hothouse were heated by hot water in this country by

Count Chabannes as early as 1816, the invention is claimed by Mr, Anthony Bacon,

and Mr. Atkinson ; though it appears that neither of these gentlemen began their experiments

till 1822, six years after the “ water calorifère ” had been exhibited to the

British public. Wo have no doubt, however, that the idea was, to a certain extent, if

not altogether, original, both on the part of Mr. Bacon and Mr. Atkinson;, hccausc

neither of these gentlemen seem to have been at all aware of what had been either done

or written by Bonncmain or by Count Chabannes. Mr. Bacou stated, that lie took the

idea of heating hothouses by hot water, from having seen, above eighteen years prcMously

to 1822, a leg of mutton boiled in a horse pad. The breech of a gun barrel was put in

the fire, and, the muzzle being inserted in the side of the pail near the bottom, the water

in the pail was made to boil, and kept boiling. Mr. Atkinson is said to have been led to

think it would answer to heat forcing-houses with hot water, from an experiment which

he had seen made by the late Count Rumford, about the year 1799. Whatever may be

said respecting the invention, nothing can be more certain than that Mr. Atkinson was

the first who successfully applied this mode of heating to hothouses.

2134. T he ap p lication o f heat hy hot w a ter has spread rapidly, not only in garden strac-

tm-es, but in dwelling-houses, and in heating manufactories and public buildings ; so

that at the present time it has almost entirely superseded steam.

2135. The advantages which this mode of heating has over steam are, that as soon as

heat is conveyed by the fire to the water, a circulation takes place in the apparatus, by

which moans heat is immediately communicated to the house, or body to be heated ;

whereas in heating by steam, none can be communicated till after the water has been

made to’boil. A second advantage which hot water has over steam, is that of producing

a mass of heated matter, which parts with its heat slowly ; whereas, from the gasiform

nature of steam, unless it is employed to heat other bodies to its own tempcratm-e (as in

the mode of its application to stones, &c., already described, § 2125.), it leaves uo supply

of heat after it has been withdrawn. i ^

2136. The improvements which have been made in the mode of heating by hot water

are various. At first, the water was chiefly circulated in tubes perfectly horizontal m

thcir direction. ■ Soon after, it was found that it might be circulated m tubes irregular

in point of horizontal direction, and both below and above the level of the boiler. Two

eno-ineers, Kewley of London, and Fowler of Devonshire, have circulated water m the

two legs of a siphon, which is found to increase tho rapidity of its motion ; and broad

flat pipes have been used, instead of cylindrical ones, as giving out the heat more rapidly.

It is but justice to the memoiy of Count Chabannes to state, that most of these methods

seem to have been known to him ; and as it is certain that he merely echoed the inventions

of Bonneraain, they were in all probability anticipated by that engineer. The most remarkable

improvement that has been made with hot water is perhaps, however, that of

circulating it in liennetically scaled tubes (§ 2144.),by which the water may be raised toa

temperature considerably above the boiling point ; and thus not only the heat is conveyed

to as great a distance as it can be by steam, but much smaller pipes may be employed m

heating. Thus, a pipe of water of 1 in. in diameter, outside measure, heated to the

temperature of 280°, will give out as much heat as one of 4 in. in diameter heated

to 180°. Hcncc the gi-cat economy of this mode of heating, besides other adiraiitages.

These are, the little attention that is required to keep the apparatus supplied with water;

the certainty that, while the apparatus is iu repair, no steam ivill escape from the joints ;

the more agreeable appearance of these small pipes than that of the large ones, which

must necessarily be employed in circulating water not under compression ; and the convenience

of being able to introduce them in situations where there is not room for pipes

of larger dimensions. Perhaps to these advantages may be added that of no boiler being

requisite ; the pipes foi-ming a coil round the fireplace in such a manner that, while the

heated water passes out at tlie top of the coil, the cold enters at tlie bottom, to be reheated

in ascending to the top. Tlic theory of the circulation of hot-water in open vessels will

be found laid down in great detail by Mr. Tredgold in the Transactions o f the Lond on

H o rt. Soc. vol. vii. part iv. The power of imitating other climates and other seasons,

Tredgold observes, than those which nature aff'ords us, is known and valued as it ought

to be ; yet it remains difficult even to imagine the extent to which this power may be

applied : in this age it produces luxuries, of which few can enjoy more than the commonest

species ; but in the next, nay, even in our oivn, there is a reasonable expectation

of a considcrabie addition to the quantity and quality of these artificial productions, as

well as to the vast sources of pleasure and information they afford to the admirers and

the students of natiire. The vehicle employed to convey and distribute heat in the new

process is water ; for it lias been found that, in an arrangement of vessels connected by

])ipes, the whole of the water these vessels and pipes contain may be heated by applying

heat to one of the vessels ; and that in this manner a great extent of heating surface,

and a large body of hot water to supply it, may be distributed so as to maintain an elevated

and regular temperature in a liouse for plants, or, indeed, in any other place requiring

heat. The obvious advantages of this method are, first, the mild and equal

temperature it produces, for the hot surface cannot be hotter than boiling water ;

secondly, the power of heating such a body of water as will preserve the temperature of

the house many hours without attention ; and, thirdly, the freedom from smoke, or the

other effluvia of smoke fines. In houses for plants, these advantages are most important.

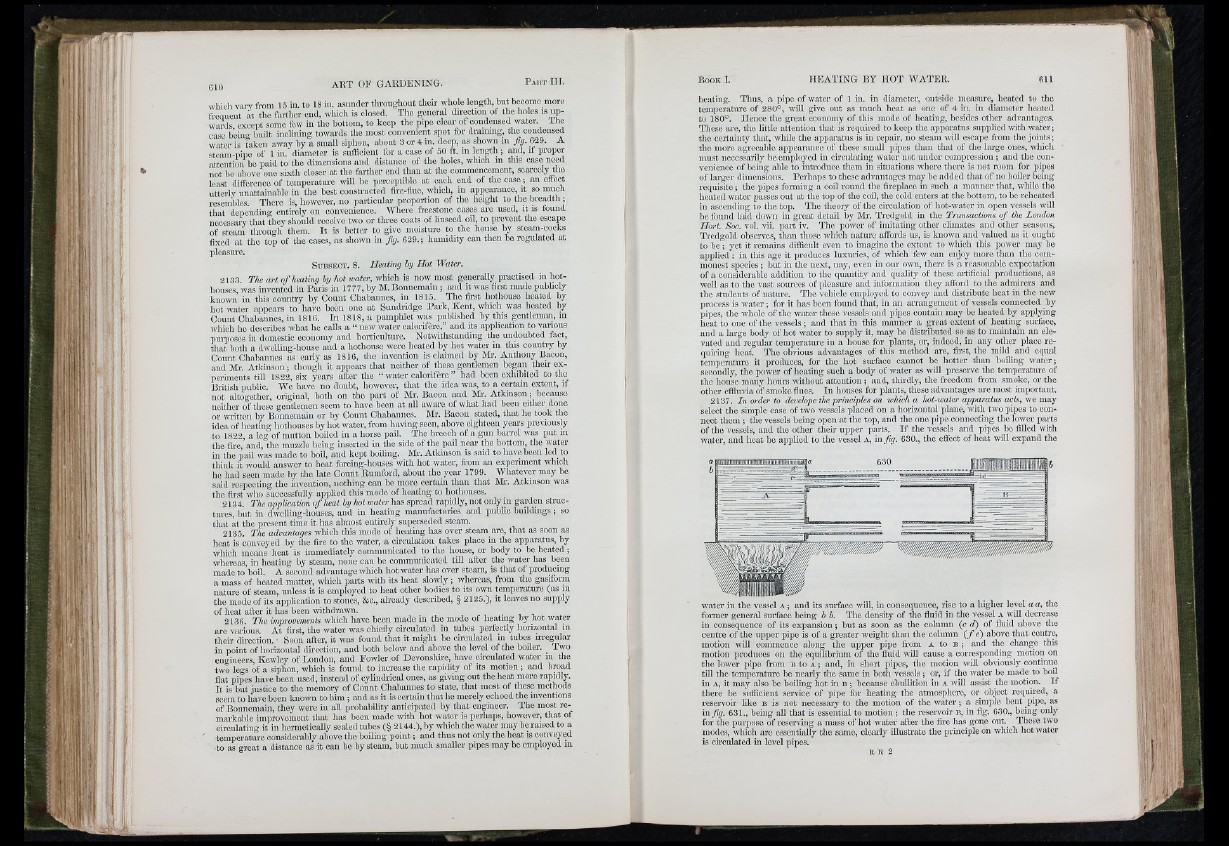

2137. I n order to develope the prin c ip les on w hich a h ot-w ater ap p aratus acts, we may

select the simple case of two vessels placed on a horizontal plane, with two pipes to connect

them ; the vessels being open at the top, and the one pipe connecting the lower parts

ofthe vessels, and the other their upper parts. If the vessels and pipes bo filled with

water, and heat be applied to the vessel a, m fig . 630., the effect of heat will expand the

water in the v-csscl a ; and its smface will, in consequence, rise to a higher level a a, the

former general surface being h b. The density of the fluid in the vessel a will decrease

in consequence of its expansion ; hut as soon as the column (c d ) of fluid aboi'c the

centre of the upper pipe is of a greater weight than the column ( / e) above that centre,

motion will commence along the upper pipe from a to b ; and the change this

motion produces on the equUibriiim of the fluid will cause a corresponding motion on

the lower pipe from b to a ; and, in short pipes, the motion will obviously continue

till the temperature be neai-ly the same in both vessels ; or, if the water be made to boil

in a , it may also be boiling hot in b ; because ebullition in a will assist the motion. If

there be sufficient service of pipe for heating the atmosphere, or object required, a

reservoir like b is not necessary to the motion of the water ; a simple bent pipe, as

in fig . 631., being all that is essential to motion ; the reservoir b, in fig. 630., being only

for the purpose of reserving a mass of hot water after the fire has gone out._ These two

modes, which are essentially the same, cleai-ly illustrate the principle on wliich hot water

is circulated in level pipes.

R R 2

'.JJ