í' i. \- ú

li II i

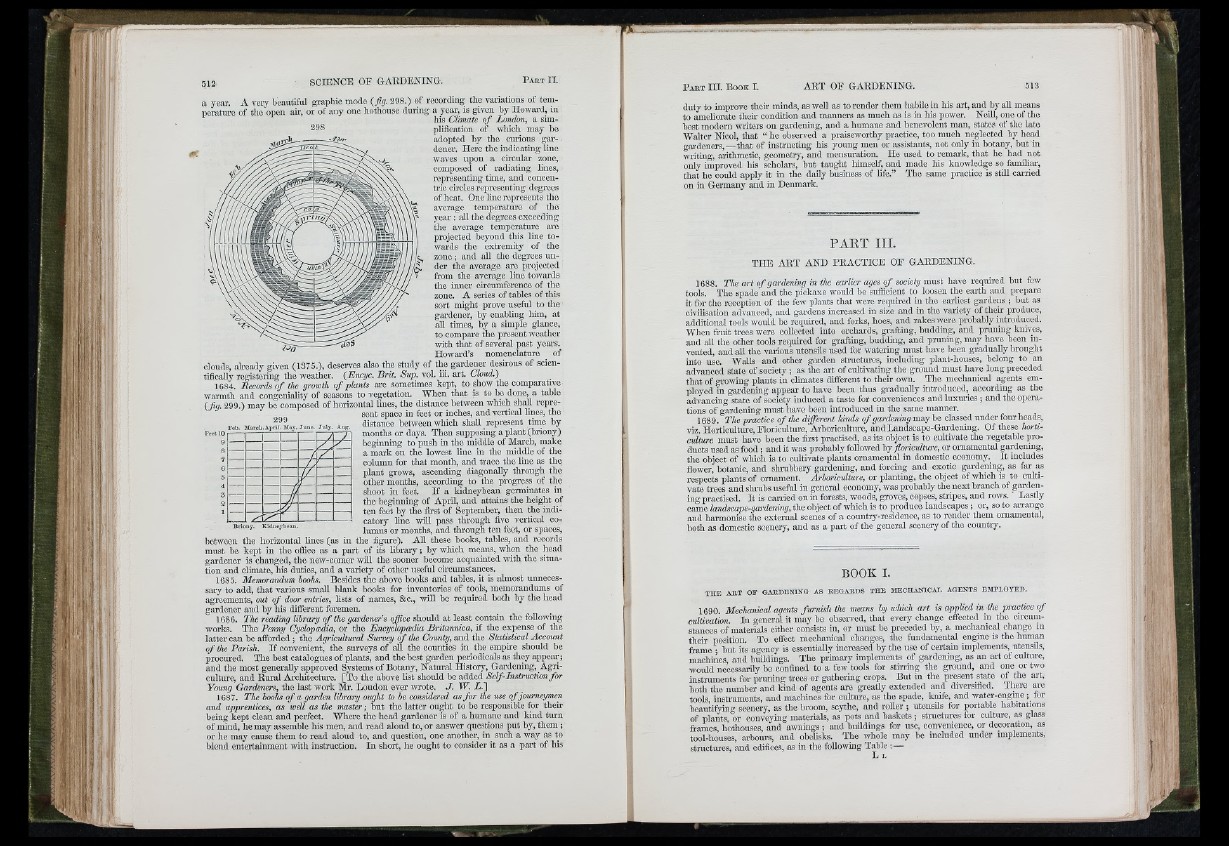

a year. A very beautiful graphic mode (fig. 298.) of recording tho variations of temperature

of the open air, or of any one hothouse during a year-, is given by Howai-d, in

his Climate o f London, a sim-

298 plification of which may be

adopted by the curious gardener.

Here the indicating line

waves upon a circular zone,

composed of radiating lines,

representing time, and concentric

circles representing degrees

of heat. One line represents the

average temperature of the

year : all the degrees exceeding

tho average temperature are

projected beyond this line towards

the extremity of the

zone ; and all the degrees un der

the average are projected

from tho average line towai'ds

the inner circumference of the

zone. A series of tables of tliis

sort miglit prove useful to tho

gardener, by enabling him, at

all times, by a simple glance,

to compare the present weather

with that of several past ycai-s.

Howard’s nomenclature _ of

clouds, already given (1375.), deseiwes also the study of the gardener desirous of scientifically

registering tho weather. (Encyc. Brit. Sup. vol. iii. art. Cloud.)

1684. Records o f the growth o f plants arc sometimes kept, to show the comparative

w'armth and congeniality of seasons to vegetation. When that is to be done, a table

( fiq. 299.) may be composed of horizontal lines, the distance between which sbafi represent

space in feet or inches, and vertical lines, tho

distance between which shall represent time by

months or days. Then supposing a plant (briony)

beginning to push in the middle of March, make

a mark on the lowest line in the middle of the

column for that month, and trace the line as the

plant gi'ows, ascending diagonally through the

other months, according to the progress of the

shoot in feet. I f a kidneybean germinates in

the beginning of April, and attains the height of

ten feet by the first of September, then the indicatory

line wifi pass through five vertical co-

299

Fob. March. April. May. Ju n e . Ju ly . Aug.

Briony. Kidneybean. lumus or months, and tliTOugh tcu fcct, or spaces,

between the horizontal lines (as in the figure). All these ^ books, tables, and records

must be kept in the office as a part of its library ; by which means, when the head

gardener is changed, the new-comer will the sooner become acquainted with the situation

and climate, his duties, and a variety of other useful circumstances.

1685. Memorandum boolis. Besides the above books and tables, it is almost unnecessary

to add, that various small blank books for inventories of tools, memorandums of

agreements, out o f door entries, lists of names, &c., wifi be required both by the head

gardener and by his different foremen.

1686. The reading library o fth e gardener’s office should at least contain the following

works. The Penny Cyclopoedia, or the Encyclopædia Britannica, if the expense of the

latter can be afforded ; the Agricultural Survey o f the County, and the Statistical Account

o f the Parish. I f convenient, the smweys of all the counties in the empire should be

procured. The best catalogues of plants, and the best garden periodicals as they appear;

and the most generaUy approved Systems of Botany, Natural History, Gardening, Agriculture,

and Rm*al Arcliitecture. [To the above list should be added Self-Instruction fo r

Young Gardeners, the last work Ml\ Loudon ever wrote. J . W. Z .]

1687. The books o f a garden library ought to be considered as fo r the use ofjourneymen

and apprentices, as well as the master ; but the latter ought to he responsible for their

being kept clean and perfect. Where the head gardener is of a humane and kind turn

of mind, he may assemble his men, and read aloud to, or answer questions put by, them ;

or he may cause them to read aloud to, and question, one another, in such a way as to

blond entertainment with instruction. In short, he ought to consider it as a part of his

duty to improve tlieir minds, as well as to render them habile in his art, and by all means

to ameliorate them condition and manners as much as is in his power. Neill, one of the

best modem writers on gardening, and a humane and benevolent man, states of the late

Walter Nicol, that “ he observed a praiseworthy practice, too much neglected by head

gardenci's,— that of instracting his young men or assistants, not only in botany, but in

wi'iting, arithmetic, geometry, and mensuration. He used to remark, that he had not

only improved his scholai's, but taught himself, and made liis knowledge so familiar,

that he could apply it in the daily business of hfe.” Tho same practice is stiU earned

on in Germany and in Denmark.

P A E T I I I .

TH E A R T AND PRACTICE OF GARDENING.

1688. The art o f gardening in the earlier ages o f society must have required but few

tools. The spade and the picko.xe woidd be sufficient to loosen tbe earth and prepare

it for the reception of the few plants that were required in the eailiest gardens ; but as

civihsation advanced, and gardens increased in size and in tho variety of thcir produce,

additional tools would be required, and forks, hoes, and rakes were probably intvodiiccd.

When fruit trees were collected into orcliards, graftmg, budding, and prumng kmves,

and all the other tools required for grafting, budding, and pruning, may havo been ni-

vented, and all the various utensils used for watering must have hoen gradually brought

into use. WaUs and other garden stiucturcs, including plant-liouscs, belong to an

advanced state of society ; as the art of cultivating the gromid must have long preceded

that of growing plants in chmates different to their own. The mechanical agents employed

in gai-dening appeal- to havo been thus gradually introduced, accordmg as tho

advancing state of society induced a taste for conveniences and luxuries ; and tho operations

of gardening must have been introduced in the same manner.

1689. The practice o f the different kinds o f gardening may be classed under four heads,

viz. Hoi-ticultm-o, Floriculture, Avboriculture, andLandscape-Gai-dening. Of these horticulture

must havo heen the first practised, as its object is to cidtivate the vegetable products

used as food ; and it was probably followed by floriculture, or ornamental gardening,

tho object of which is to cultivate plants ornamental in domestic economy. I t includes

flower, botanic, and shrubbery gardening, and forcing and exotic gardening, as far as

respects plants of ornament. Arboriculture, or planting, the object of which is to cultivate

trees and shrubs useful in general economy, was probably the next branch of gai-dening

practised. I t is carried on in forests, woods, groves, copses, stripes, and rows. ' Lastly

came landscape-gardening, the object of which is to produce landscapes ; or, so to an-ange

and harmonise the external scenes of a country-rcsidence, as to render them ornamental,

both as domestic scenery, and as a pai-t of the general scenery of the coimtry.

B O O K I .

TH E ART OF GABHENINO AS REGARDS TH E MECHAJSICAL AGENTS EMPLOTED.

1690 Mechanical agmts furnish the means by which art is applied in the practice o f

cultivation. I n general it may be observed, that every change effected in the cu-oum-

stances of materials either consists in, or must bo preceded by, a mechanical change in

their position. To effect mechanical changes, the fundamental engine is the human

frame ■ but its agency is essentially increased by the use of certam implements, utensils,

machines, and buildings. Tho primary implements of gardening, as an art of culture,

would necessarily be confined to a few tools for stin-ing the ground, and one or two

instruments for pruning trees or gathering crops. Bnt in the present state of the art,

both the number and kind of agents are gi-eatly extended and diversified. There are

tools, insti-mnents, and machines for culture, as the spade, knife, and water-engine ; ioi-

beautifying scenery, as tho broom, scythe, and roUor ; utensils for portable habitations

of plants, or conveying materials, as pots and baskets ; stractures for cniture, as glass

frames, hothouses, and awnings; and huildings for nse, convenieiioe, or decora,tion, as

tool-houses, arbours, and obelisks. The whole may be included under implements,

structures, and edifices, as in the following Table ; —

L I.