' L i !

liri i

: ' 'i

j i'- i ' : . 1

’ fi'i

i

i ' i l u

i i 1 ■'

1" ( !

■ I . ') '; ’

I

. 1 1

i :

y • i i l , i

ll' l i

A R T O F G A R D E N IN G .

down. When pyramidal trees ai’C so

[>nincd tliat the liorizontal branches

form stages above one another, they

are termed chaudelicr-like, or cn

girandole.

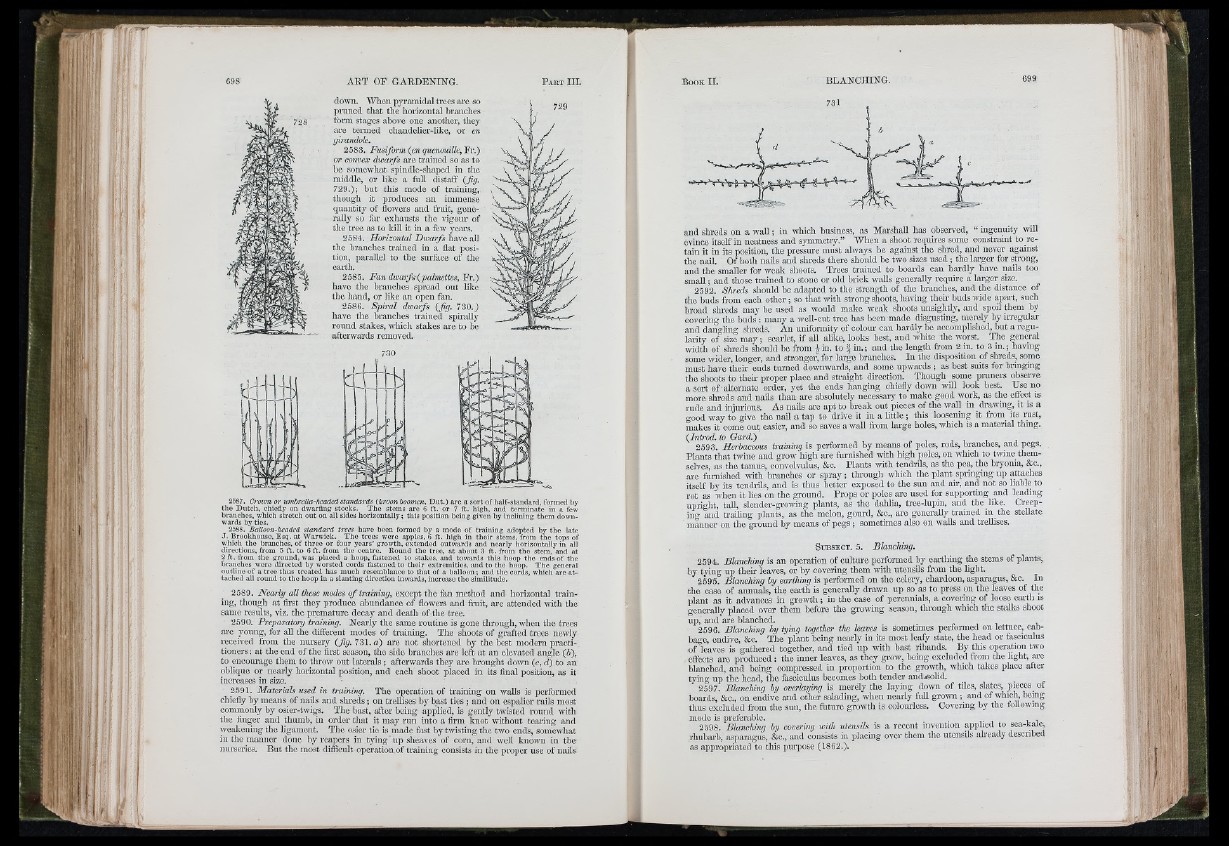

2583. F u s ifo rm (en quenouille, Fr.)

o r convex d w a rfs ai'O trained so as to

be somewhat spindle-shaped in the

middle, or like a fuU distaff (fig .

729.); but this mode of training,

though it produces an immense

quantity of flowers and fruit, generally

so far exhausts the vigoiu* of

the tree as to kill it in a few years.

2584. H o riz o n ta l D w a rfs have all

the branches trained in a flat position,

parallel to the surfiice of the

earth.

2585. F a n d w a rfs (p ahnettes,E Y .')

have the branches spread out like

the hand, or like an open fan.

2586. S p ir a l d w a rfs (fig . 730.J

liave the branches trained spfrally

round stakes, wliich stakes ai’e to be

afterwards removed.

2587. Croton o r umbrella-headed s ta n d a rd s (k ro o n boomen, Du t.) are a sort of half-standard, formed by

the Dutch, chiefly on dwarfing stocks. The stems are 6 ft. or 7 ft. high, and terminate in a few

branches, which stretch out on all sides horizontally; this position being given by inclining them downwards

by ties.

2588. Balloon-headed s ta n d a rd tre e s have been formed by a mode of training adopted by th e lato

J . Brookhouse, Esq. a t Warwick. The trees were apples, 6 ft. high in their stems, from the tops of

which the branches, of three or four years’ growth, extended outwards and nearly horizontally in all

directions, from 5 ft. to 6 ft. from th e centre. Round the tree, a t about 3 ft. from th e stem, and at

2 ft. from the ground, was placed a hoop, fastened to stakes, and towards th is hoop th e ends of the

branches were directed by worsted cords fastened to their extremities, and to the hoop. The general

outline of a tree thus treated has much resemblance to that of a balloon; and the cords, which are a ttached

all round to th e hoop in a slanting direction inwards, increase the similitude.

2589. Nearly all these modes o f training, except the fan method and horizontal training,

tliough at first they produce abundance of fiowers aud fimit, ai*e attended with the

same rcsiilts, viz. the premature decay and death of the tree.

2590. Preparatory training. Nearly the same routine is gone through, when the trees

are young, for all the different modes of training. The shoots of grafted trees newly

received from the nursery 731. a) are not shortened by the best modern practitioners:

at the end of the first season, the side branches ave left at an elevated angle ( I ) ,

to encourage them to throw out laterals; afterwards they are brought down (c, d ) to an

oblique or nearly hoiizoutal position, and each shoot placed in its final position, as it

increases in size.

2591. Materials used in training. The operation of training on walls is performed

chiefly by means of nails and shi-ecls; on trellises by bast ties; and on espalier rails most

commonly by osier-twigs. The bast, after being applied, is gently twisted round witli

the finger and thumb, in order that it may run into a firm knot without tearing and

weakening the ligament. The osier tie is made fast by twisting the two ends, somewhat

in the manner done by reapers in tying'up sheaves of corn, and well known in the

nurseries. But the most difficult operation of training consists in the proper use of nails

B o o k I I. b l a n c h i n g .

731

699

and shreds on a wall; in which business, as Marshall has observed, “ ingenuity will

evince itself in neatness and symmetry.” When a shoot requires some constraint to retain

it in its position, the pressure must always be against the shred, and never against

the nail. Of both nails and shi-eds there should be two sizes used; the larger for strong,

and the smaller for weak shoots. Trees trained to hoards can hardly have nails too

small; and those trained to stone or old brick walls generally require a larger size.

2592. Shreds should be adapted to the strength of the branches, and the distance of

the buds from each other; so that with strong shoots, having thcir buds wide apart, such

broad shreds may be used as would make weak shoots unsightly, and spoil them by

covering the buds : many a well-cut tree has been made disgusting, merely by in-egular

and dangling shreds. An uniformity of colour can hardly be accomplished, but a regularity

of size may; scarlet, if all alike, looks best, and white the worst. The general

ividth of shreds should he from ^in. to ^ in.; and the length from 2 in. to 3 in.; having

some wider, longer, and stronger, for large branches. In the disposition of shreds, some

must have their ends turned downwards, and some upwards; as best suits for bringing

the shoots to their proper place and straight direction. Though some pruners observe

a sort of alternate order, yet the ends hanging chiefly down will look best. Use no

more shreds and nails than are absolutely necessary to make good work, as the effect is

rude aud injurious. As nails arc apt to break out pieces of the wall in drawing, it is a

good way to give the nail a tap to drive it in a little; this loosening it from its rust,

makes it come ouf easier, and so saves a wall ft-om large holes, which is a material thing.

(In tro d . to G a rd .) ,

2593. Herbaceous tra in in g is performed by means of poles, rods, branches, and pegs.

Plants that twine and grow liigh are furnished with high poles, on which to twine themselves,

as the tamus, convolvulus, &c. Plants with tendrils, as the pea, the bryoma, &c.,

ai-o furnished with branches or spray; through which the plant springing up attaches

itself by its tendrils, and is thus better exposed to the sun and air, and not so liable to

rot as when it lies on the ground. Props or poles arc used for supporting and leading

upright, taU, slender-growing plants, as the dalilia, trce-lupin, and the like. Creeping

and trailing plants, as the melon, gom-d, &c., ai-e generally trained in the stellate

manner on the ground by means of pegs; sometimes also on walls and treUises.

Su b se ct. 5. B la nc h in g .

2594. B la n c h in g is an operation of culture performed by earthing the stems of plants,

by tying up their leaves, or by covering them with utensils from the light.

2595. B la n c h in g hy earthing is performed on the celery, chardoon, asparagus, &c. In

the case of annuals, the eaith is generally drawn up so as to press on the leaves of the

plant as it advances in growth ; in the case of perennials, a covering of loose earth is

generally placed over them before the gi-owing season, through which the stalks shoot

up, and are blanched.

2596. B la n c h in g by tying togethei' the leaves is sometimes performed on lettuce, cabbage,

endive, &c. The plant being nearly in its most leafy state, the head or fasciculus

of'leaves is gathered together, and tied up with bast ribands. By this operation two

effects are produced: the inner leaves, as they grow, being excluded from the light, are

blanched, and being compressed in proportion to the growth, which takes place aftcr

tying up the head, the fasciculus becomes both tender and«olid.

2597. B la n c h in g by overlaying is merely the laying down of tiles, slates, _pieccs_ of

boards, &c., on endive and other salading, when neai-ly full grown ; and of which, being

thus excluded fi-om the sun, the future growth is colourless. Covering by the following

mode is preferahle. _ . .

2598. B la nc h in g hy covering w ith utensils is a recent invention applied to sca-kale,

rhuhai-b, asparagus, &c., and consists in [fiacing over them the utensils ah-cady described

as appropriated to this purpose (18G2.).