?■: ?

I " î

A E T O F G A E D E N IN G . P a r t I I I .

first of whicli wc have any record was that erected by Solomon de Cans, at Heidelberg,

about 1619, to shelter some orange trees planted in the free ground there. It consisted

merely of a movable wooden frame, with a wooden span roof, and wooden shutters on

the sides (Jig . 593.). This frame was put up at Mchaelmas and taken down at

Book I. PERMANENT HORTICULTURAL STRUCTURES. 585

595

593

T T

Easter every year ; bnt it was found so troublesome, that we find Solomon de Caus, m

his A ccount o f Heidelberg, observes that he had advised the king to remove it, and to

supply its place by a constniction of freestone. (See p. 140.)

2044. T h e orangery w ith a n opaque ro o f and glass sides was the next step made in the

construction of plant-houses; and buildings of this description are still frequently to be

met with, as shoivn in Jig. 594., in which an opaque-roofed orangery is shown in com-

biiiation with two modem curviliueai* glass hothouses. Such was the greenliouse in the

Apothecaries’ garden at Chelsea, mentioned hy Ray, in 1684 (L e tte rs , p. 174.), as being

heated by hot embers put in a hole in the floor ; a practice still extant in some paits of

Noi-mandy, and to which, as is well known, the curfew, or couvrefeu bell refers. The

same general form of house, with the addition of a furnace or oven, is given by Evelyn

in the different editions of his K ale nd arium .

2045. T h e next e ra o f improvement may be dated 1717, when Switzer published a plan

for a forcing-house, suggested by the Duke of Rutland’s gi*aperies at Bclvoir Castle.

Miller Bradley, and others, soon after, published designs, in which glass roofs were introduced

; and between the middle and the end of the last ccntuiy, Speedily and

Abercrombie in England, and Kyle and Nicol in Scotland, made various improvements

in forcing-houses, as to general form, internal an-angements, and mode of heating.

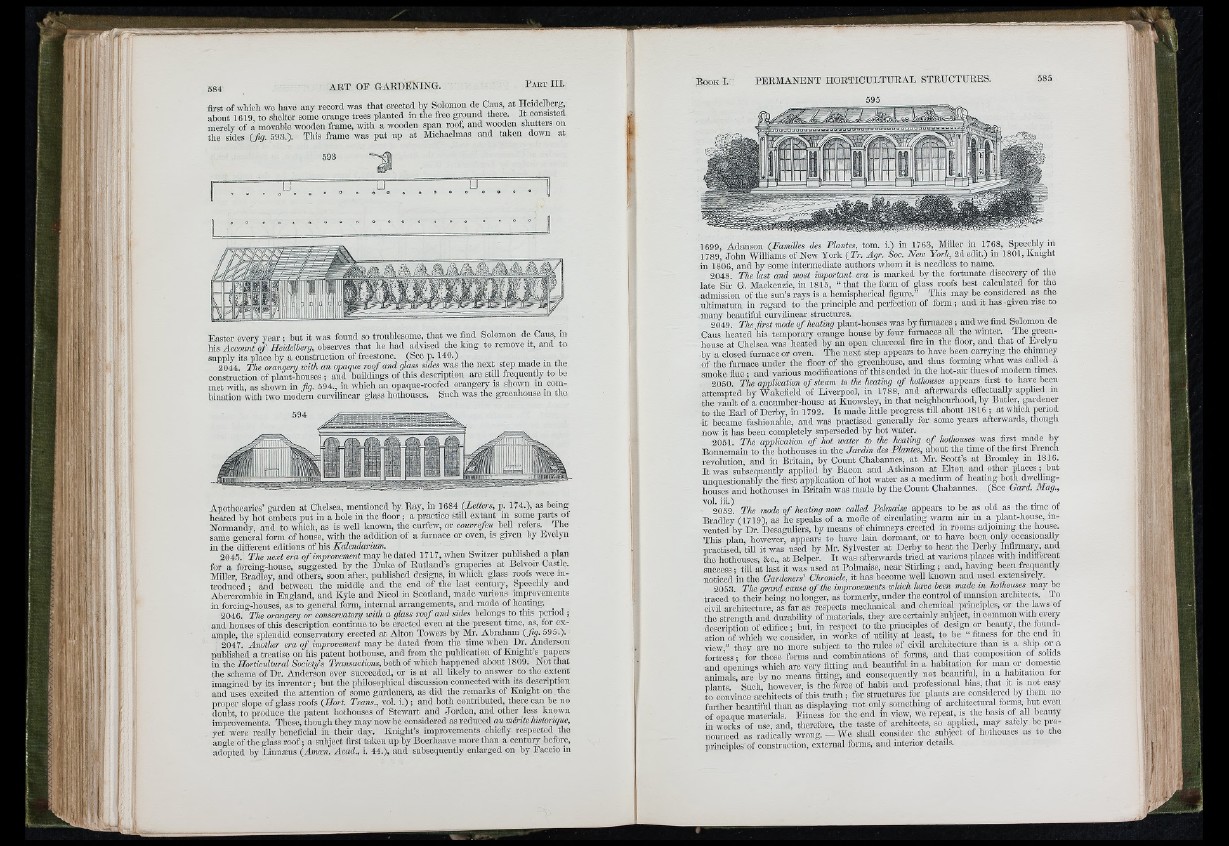

2046. T h e orangery o r conservatory w ith a glass r o o f and sides belongs to tliis period ;

and houses of this description continue to be erected even at the present time, as, for example,

the splendid conservatory erected at Alton Towers by Mr. Abraham ( f g . 595.).

2047. A n o th e r era o f improvement may be dated from the time when Dr. Anderson

published a treatise on his patent hothouse, and from the publication of Knight’s papers

in Ûid H o rtic u ltu ra l Society’s Trawsacitows, both of which happened about 1809. Not that

the scheme of Dr. Anderson ever succeeded, or is at all likely to answer to the extent

imagined by its inventor ; but the philosophical discussion connected with its description

and uses excited the attention of some gardeners, as did the remarks of Knight on the

proper slope of glass roofs (H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. i.) ; and both contributed, there can be no

doubt, to produce the patent hothouses of Stewart and Jorden, and other less known

improvements. These, though they may now be considered as reduced a u m érite historique,

yet were reallv beneficial in their day. Knight’s improvements chiefly respected the

angle of the glass roof ; a subject first taken up by Boerhaave more than a century before,

adopted by Linnæus (Amcen. A cad ., i. 44.), and subsequently enlarged on by Faccio in

1699, Adanson (F am ilie s des P lantes, tom. i.) in 1763, Miller in 1768, Speechly in

1789, John Williams of New York ( T r . A g r. Soc. N e w Y o rk , 2d edit.) in 1801, Knight

in 1806, and by some intermediate authors whom it is needless to name.

2048. T he la s t a nd most im p ortan t era is marked by the fortunate discoveiy of the

late Sir G. Mackenzie, in 1815, “ that the form of glass roofs best calculated for the

admission of the sun’s rays is a hemispherical figiire.” This may be considered as the

ultimatum in regard to the principle and perfection of form; and it has -given rise to

many beautiful curvilinear structures. ^

2049. T h e f r s t mode o f heating plant-houses was by furnaces; and we find Sofomon de

Caus heated his temporary orange house by four furnaces all the winter. The greenhouse

at Chelsea was heated by an open chai-coal fire in the floor, and that of Evelyn

by a closed furnace or oven. The next step appears to have been carrying the chimney

of the fm-nace under the floor of the greenliouse, and thus forming what was called a

smoke flue; and various modifications of this ended in the hot-air flues of modera times.

2050 T he ap p lication o f steam to the heating o f hothouses appears first to have been

attempted by Wakefield of Liverpool, in 1788, and afterwai-ds effectually applied m

tlic vault of a cucumber-house at Knowsley, in that neighbom-hood, by Butler, gardener

to the Eai-1 of Derby, in 1792. It made little progress till about 1816 ; at which period

it became fasliionablc, and was practised generally for some yeai-s afterwards, though

now it has been completely superseded by hot water.

2051. T h e ap p lication o f hot w a ter io the heating o f hothouses was first made by

Bonneraain to the hothouses in the J a rd in des P la nte s, about the time of the first French

revolution, and in Britain, by Count Chabannes, at Mr. Scott’s at Bromley m 1816.

It was subsequently applied by Bacon and Atkinson at Elton and other places; but

unquestionably the first application of hot water as a medium of heating both dwcUmg-

houses and hothouses in Britain was made bythe Count Chabannes. (See G a rd . M a g .,

™2052. T he mode o f heating now called Polm aise appeai-s to be as old as the time of

Bradley (1719), as he speaks of a mode of cii-culating warm air in a plaiit-housc, invented

by Dr. Desaguliers, by means of chimneys erected in rooms adjoining the house.

This plan however, appears to have lam dormant, or to have been only occasionally

practised, till it was used by Mr. Sylvester at Derby to heat the Derby Infii-mary, and

the hothouses, &c., at Belper. It was aftei-wards tried at various places with indifferent

success; till at last it was used at Polmaise, near Stirling; and, having been frequently

noticed in the Gardeners’ Chronicle, it has become weU known and used extensively.

2053 T h e grand cause o fth e improvements w hich have been made in hothouses may be

traced to their being no longer, as formerly, under the control of mansion architects. To

civil architectm-e, as far as respects mechanical and chemical principles, or the laws ot

the strength and durability of materials, they are certainly subject, in common with eveiy

description of edifice; but, in respect to the principles of design or beaitty, the foundation

of which wc consider, in works of utility at least, to be “ fitness for the end iii

view ” they are no more subject to the rules of chdl architcctiire than is a ship or a

fortress • for those forms and combinations of forms, and that composition of solids

and openings which are very fitting and beautiful in a habitation for man or domestic

animals, are by no means fitting, and consequently not beautiful, in a habitation for

plants Such however, is the force of habit and professional bias, that it is not easy

to conVince architects of this trath; for stractures for plants are considered by them no

further beautiful than as displaying not only something of ai-chitectiiral foms, but even

of opaque materials. Fitness for the end in view, we repeat, is the basis of dl beauty

in works of use, and, therefore, the taste of architects, so applied, may sately be pro-

uonnced as radically wrong. — We shall consider the subject of hothouses as to the

principles'of construction, external forms, and interior details.

m i

i'-K;' Ic.k';

sm?i ?