il

' ¡1

f l

I "

benches or tables, for potting cuttings or bulbs, sowing seeds, preparing cuttings, niimbcr-

tiillies, painting and naming them, preparing props for plants, hooks for layers, lists for

wall-trees, making biiskets, wattled hurdles, and a great variety of other operations pcr-

fonncd in winter, or severe weather, when little or nothing can be done in the open air.

It may by some be thought too great a refinement to warm such sheds ; but if work is

really expected to be done in them during cold weather, the saving will soon be rendered

obvious.

2201. I n sm all gardens, where there are no hothouses, one small building is generally

devoted to all the purposes for which the office, seed, tool, and fruit rooms, and working-

sheds, arc nsed. It should be fitted up with some degi'ee of attention to the vai-ious

uses for which it is designed, and a fire-place never omitted.

2202. B u ild in g s f o r ra is in g w ater. There arc various contrivances for procuring

water in garden-scenery, where it is not found in springs, rills, or lakes ; and where it is

found, of collecting and retaining it. The principal of tliese are wells, conduit-pipcs or

drains, and reservoirs.

2203. W e lls are vertical excavations in the earth ; always of such a depth as to penetrate

a porous stratum charged -with water, and mostly as much deeper as to form a

reservoir in this stratum or in that beneath it. A well otherwise excavated is a mere

tank for the water which may ooze into it from the surface strata. The form of the

well is gcneraliy circular, and to prevent the crumbling down or falling in of the sides,

this circle is lined with timber, masonry, or zones of metal. The earthy materials being

thus pressed on equally in every point of this circle, are kept in equilibrium. When

the well is not very deep, and in finn ground, this casing is built from the bottom to the

top, after the excavation is finished ; but when the soil is loose, the excavation deep, or

its diameter considerable, it is built on the top in zones, sometimes sepai-ated by horizontal

sections of thin oak boards, which, with proper management, sink down as the

excavation proceeds. There are various other modes, which those who follow this dc-

pai'tmcnt of architecture are sufficiently conversant with. Tlie height to which the

water rises in the well depends on the height of the strata which supply the water ;

occasionally it rises to the sm-face, but generally not witliin a considerable distance. In

this case it is raised by buckets and levers, by buckets and hand-machines placed over

the well, or by buckets raised by horse-machines.

2204. A n A rte s ia n w e ll is a “ cylindrical perforation bored vertically down through

one or more of tho geological strata of the eartli, till it passes into a porous gravel bed

containing water, placed under such incumbent pressure as to make it mount up through

the perforation, cither to the sm-fiice or to a liciglit convenient for the operation of a

pump. In the first case, these wells are called spouting or overflowing. This property

is not directly proportional to the depth, as might at first sight be supposed, but to the

subjacent pressure upon the water. We do not know exactly the period at which the

borer or sound was applied to tlie investigation of subterranean fountains, but we believe

the first ovei-flowing wells were made in the ancient French province of Aitois, whence

the name of Ai'tesian.” (U re ’s D ic tio n a ry o f A rts , &c., p. 57.) These wells have been

long well known on the continent of Europe, but, it is said, they have only been used in

England since the year 1791 ; the first wells of the kind being sunk in someof the small

villages near London. (Sec Jam ieson’s M echanics o f F lu id s , p. 463.)

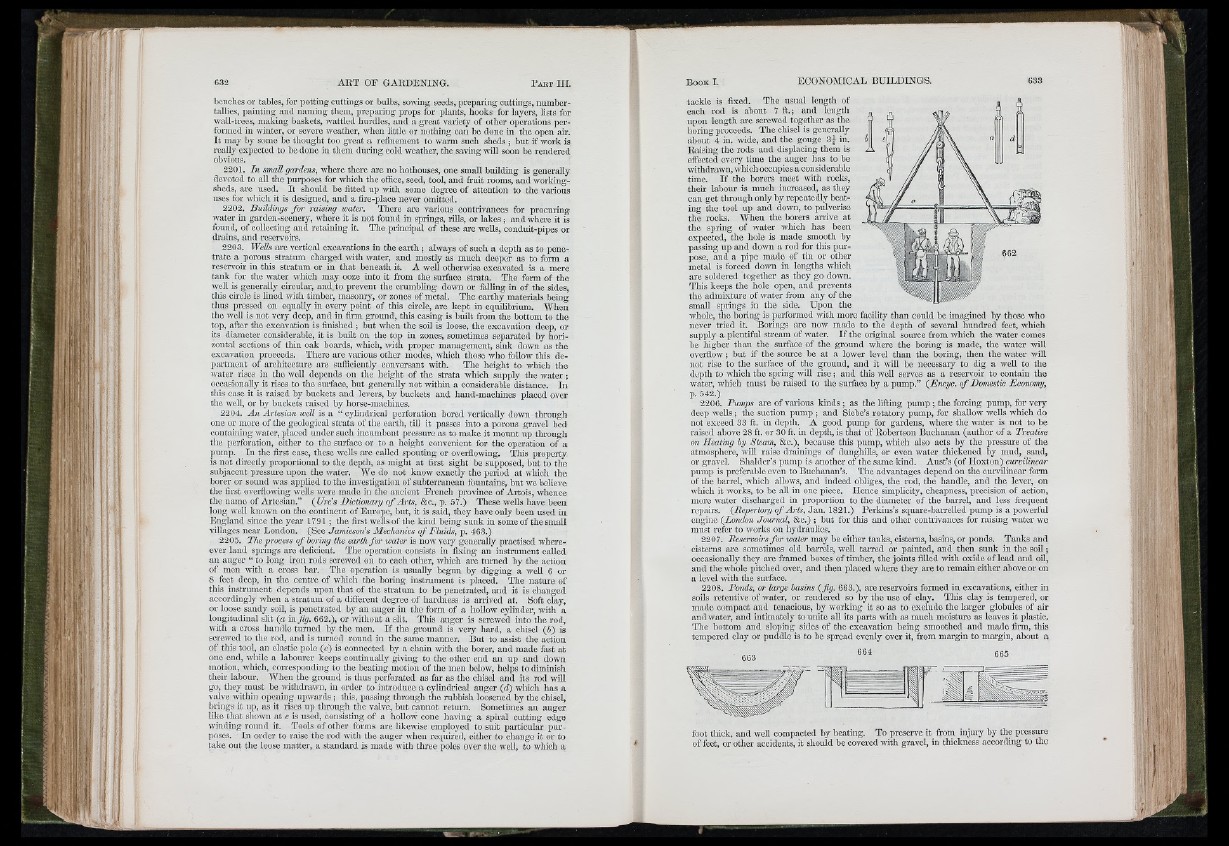

2205. Th e process o f boring the earth f u r w a te r is now very generally practised where-

ever land springs are deficient. The operation consists in fixing an insti-umcnt called

an auger “ to long iron rods screwed on to each other, which are turned by the action

of men with a cross bm*. The operation is usually begun by digging a well 6 or

8 feet deep, in tlio centre of which the boring instmmcnt is placed. The nature of

this instrument depends upon that of the stratum to be penetrated, and it is changed

accordingly when a stratum of a different degree of hardness is ai-rived at. Hoft clay,

or loose sandy soil, is penetrated by an auger in the form of a hollow cylinder, with a

longitudinal slit (a in fig . 662.), or without a slit. Tliis auger is screwed into the rod,

with a cross handle turned by the men. If the ground is very hard, a chisel (A) is

screwed to the rod, and is turned round in the same manner. But to assist the action

of this tool, an elastic pole (c) is connected by a chain with the borer, and made fast at

one end, while a labourer keeps continually giving to the other end an up and down

motion, which, corresponding to the beating motion of the men below, helps to diminish

their labour. When the ground is thus perforated as far as the chisel and its rod will

go, they must be withdrawn, in order to introduce a cylindrical auger (d ) which has a

valve within opening upwards ; this, passing through the rubbish loosened by the chisel,

brings it up, as it rises up through tlie valve, but cannot return. Sometimes an auger

like that sliown at e is used, consisting of a hollow cone having a spiral cutting edge

winding round it. Tools of other forms are likewise employed to suit particular piu'-

poscs. In order to raise the rod with the auger wlicn required, either to change it or to

take out the loose matter, a standard is made with three poles over the well, to which a

tackle is fixed. The usual length of

each rod is about 7 ft.; and length

upon length are screwed together as the

boring proceeds. The chisel is generally

about 4 in. wide, and the gouge 3^ in.

Raising the rods and displacing them is

effected every time the auger has to be

withdrawn, which occupies a considerable

time. If the borers meet with rocks,

their labour is much increased, as they

can get through only by repeatedly beating

the tool up and down, to pulverise

the rocks. When the borers arrive at

the spring of water wliich has been

expected, the hole is made smooth by

passing up and down a rod for tliis piu'-

pose, and a pipe made of tin or other

metal is forced down in lengths wliich

are soldered together as they go down.

This keeps the hole open, and prevents

the admixture of water from any of the

small springs in the side. Upon the

whole, the boring is perfoi-med with more facility than could be imagined by those who

never tried it. Borings arc now made to the depth of several hundred feet, which

supply a plentiful stream of water. If the original source from which the water comes

be higher than the surface of the ground where the boring is made, the water will

overflow; but if the soui'ce be at a lower level than the boring, then the water will

not rise to the surface of the ground, and it will be necessary to dig a well to the

depth to which the spring will rise; and this well seiwcs as a reservoir to contain the

water, which must be raised to the surface by a pump.” (E n c y c . o f D om estic Econom y,

p. 542.)

2206. Pum p s are of various kinds; as the lifting pump ; the forcing pump, for veiy

deep wells; the suction pump; and Sicbe’s rotatory pump, for shallow wells which do

not exceed 33 ft. in depth. A good pump for gardens, where the water is not to be

raised above 28 ft. or 30 ft. in depth, is that of Robertson Buchanan (author of a Tre a tise

on H e a tin g by Steam, &c.), because this pump, which also acts by the pressm-c of the

atmosphere, will raise drainings of dunghills, or even water thickened by mud, sand,

or gravel. ShaUlcr’s pump is another of the same kind. Aust’s (of Hoxton) c u rvilin e a r

pump is preferable even to Buchanan’s. The advantages depend on the curvilinear form

of the barrel, which allows, and indeed obliges, the rod, the handle, and tlic lever, on

wliich it works, to be all in one piece. Hence simplicity, cheapness, precision of action,

more water discharged in proportion to the diameter of the baiTcl, and less frequent

repairs. (R e p e rto ry o f A rts , Jan. 1821.) Perkins’s square-baiTciled pump is a powerful

engine (Lo nd on J o u rn a l, &c.) ; bnt for tliis and other contrivances for raising water wc

must refer to works on hydraulics.

2207. Reservoirs f o r w a te r may be either tanks, cisterns, basins, or ponds. Tanks and

cisterns are sometimes old ban-els, well tan-ed or painted, and then sunk in the soil;

occasionally they are framed boxes of timber, the joints filled with oxide of lead and oil,

and the whole pitched over, and then placed where they ai-e to remain either above or ou

a level with the surface.

2208. Ponds, o r large basins ( fig . 663.), arc reservoirs formed in excavations, either in

soils retentive of water, or rendered so by the use of clay. Tliis clay is tempered, or

made compact and tenacious, by working it so as to exclude the larger globules of air

and water, and intimately to unite all its parts with as much moisture as leaves it plastic.

The bottom and sloping sides of the excavation being smoothed and made fii-m, this

tempered clay or puddle is to be spread evenly over it, from margin to margin, about a

i :

663

foot tliick, and well compacted by beating. To preserve it from injury by the pressure

of feet, or other accidents, it should be covered with gravel, in thickness according to the