principal medium of introducing whatever is new aud valuable from the latter country

into Gcmuiuy and Denmark.

406. T/ie artists or architects o f gardens, in Germany, arc generally the land-baumeisterey,

or those architects who have directed their attention chiefly to country buildings. Where

only a kitchen or flower gai-dcn is to be formed, an apjirovcd practical gardener is commonly

reckoned sufBcicnt. I t occasionally happens, that a nobleman avIio wishes to

lay out an extensive garden, al’ter fixing on what he considers a good gardener of some

education, and capable of taking plans, sends him for a year or two to visit tho best

gardens of England, Holland, and France. On his return, he is deemed qualified to lay

out the garden recpiired ; wliich ho does, and afterwards attends to its culture, and acts

ns a garden ai-chitcct (garten-baumeistcr') to the minor gentry of Ins neighbourhood.

The oiicrativc gardeners in Germany are generally very well inibrmed.

SiJBSECT 6. German Gardening, as a Science, and as to the Authors it has produced.

407. The Germans are. a scientifc people: they are a reading people; and, in consequence,

the science of every art' in so far as dcA'clopcd in books, is more generally

knoAvn there than in any othcv countiy. Some may Avish to exccjft S cotland; but,

though the Scotch artisan reads a great deal, his local situation and limited intercourse

Avith otlicr nations subject him to tlic influence of the particular opinions in which lie

has been educated : he takes up prejudices at an early period, and Avith difiiculty admits

ncAv ideas irom books. On the other lumd, the Germans of every rank arc remarkable

for liberality of opinion : all of them tra v e l; and, in the course of seeing other states,

they fiml a vai-iety of practices and opinions, different from tliose to which they have

been accustomed : prejudice gives w a y ; tho man is neutralised ; becomes moderate in

estimating what belongs to liimself, and Avilling to Iicar and to learn irom others.

408. There are horticultural societies and professorships o f rural economy in many of the

universities ; one or tAvo gardeners’ magazines and almanaclcs of gardening ; and some

eminent vegetable physiologists are Germans. The Prussian Gardening Society, for

the number and rank of its members, and the value of its published Ti-ansactions, ranks

Avith tlic Iloiticultural Society of Lo n d o n ; and as a scicntiflc body, having an institution

for instructing young gardeners in the sciences on Avhich their art is founded, it

ranks before it and every other society. The Pomological Society at Altenburg is also

an institution Avhich has rendered important services to tlie culture of fruits. Tlicrc

are, besides, in Germany many societies, independently of those Avliicli combine agriculture

Avith gardening, to all of wliicb the a rt is much indebted. E atii in Hungary, it

appears (Brig h fs Travels'), a Gcorgicon, or college of rural economy, has been established

by Count Fcstctiz at Kcszthcly, in Avhicli gardening, including the cnlturo and management

of woods aud copses, forms a distinct professorship. The science of France may

be, and wc believe is, greater than that of Germany in this art, but it is accumulated iu

tlic c ap ital; whereas licrc it emanates from a great mimbcr of points distributed over tho

country, and is consequently rendered more available by practical men. The minds of

the gardeners of France arc, from general ignorance, less fitted to receive instruction

than those of Germany; their personal habits admit of less time for read in g ; and tlicir

climate and soil require less artificial agency. The German gardener is generally a

thinking, steady perso n ; tlic climate, in most places, requires his vigilant attention to

culture, and his travels have enlarged his views. Hence he becomes a more scientific

artisan tlian the Frenchman, and is in more general demand in otlicr countries. All

the best gardens in Poland, Russia, and Italy arc under the care of Germans.

409. The Gannans have produced few original authoi's on gardening, and none that can

be compared to Quintinye or Miller; but tlicy have translations of all the best Enropcan

books. Hirschfeld has compiled a number of Avorks, chieily on landscapc-gai-dening;

J . V- Sickler and Counsellor D id have wi-ittcn extensively on most departments of

horticulture, especially on the hardy iriiits. In regard to apples and pears, thctAvo most

scientific writers on their classification arc Manger (Anlcit. zum einer Systemat. Pomol)

and Diel. The first takes form as the foundation of his arrangement; the second takes

jointly the quality of the fruit and the peculiarities of the tree. Dicl’s system is, in our

opinion, decidedly the b e s t; in sliort, it is in pomology Avliat the natural system is iu

botany. (Gard. Mag., vol. ii. p. 445.) Truchscss is the standard author on cherries, and

Sickler on grapes and on the genus Citrus.

Sect. V. O fth e Rise, Progress, and present State o f Gardening in Switzerland,

410. Extcnmvc gardens are not to be expected in a country o f comparative equalisation

o f property, like SAvitzcrland; but noAvIierc are gardens more profitably managed, or

rnore neatly kept, than in that country. “ Nature,” Hirschfeld observes, “ has been

liberal to the inhabitants of Switzerland, and they have Aviscly profited from it. Almost

all the gardens are theatres of tme beauty, Avitliout vain ornaments or artificial dc-

eoratioiis. Convenience, not magnificence, reigns in the country-houses ; and the villas

av(! distinguished more by their romantic aud picturesque situations, than by their

architecture.” He mentions several gardens near Geneva and Lausanne ; Délices is

chieily remarkable because it was inhabited by Voltaire before he purchased Ferncy,

and L a Grange and L a Boissior are to this day Avell-knoAvu places. Ferncy is still

eagerly visited by cvciy stranger ; but neither it, nor the château of the Neckar family,

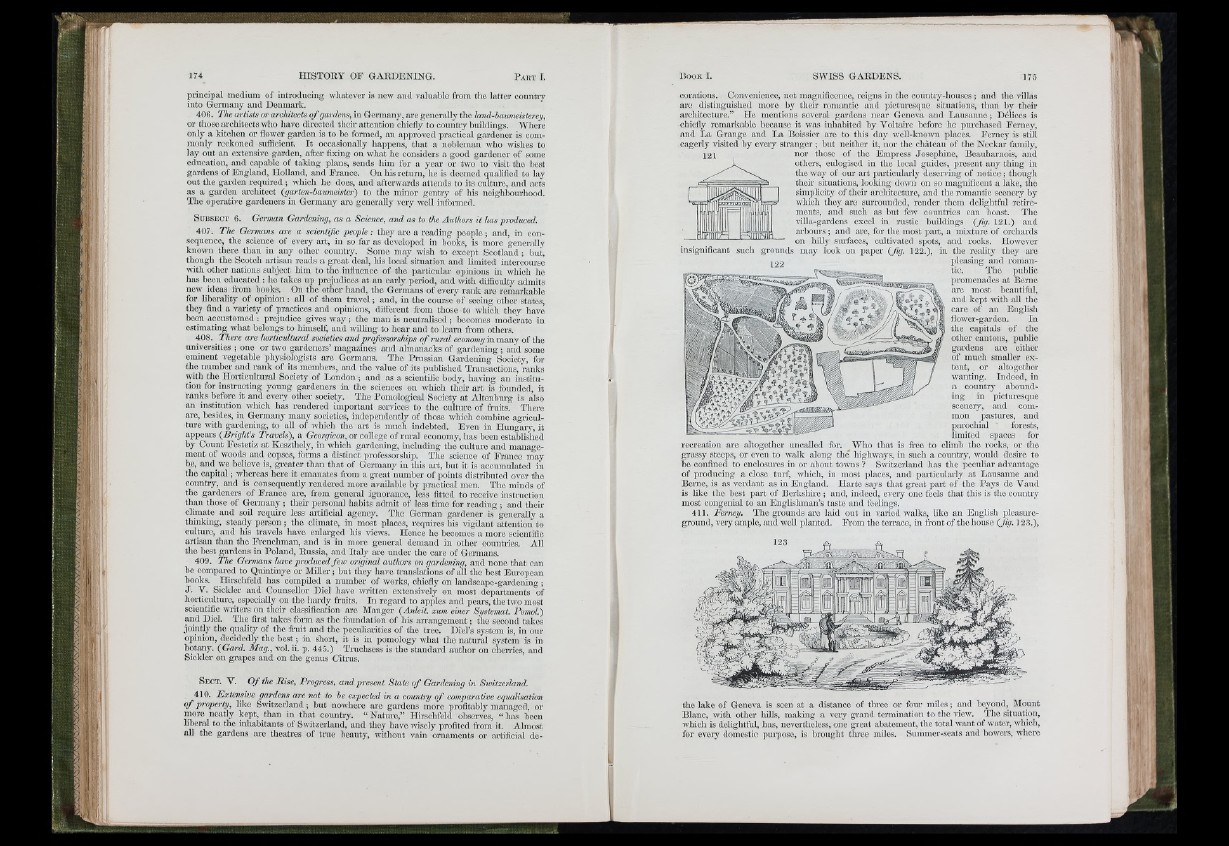

121

nor those of the Empress Josephine, Beauharnois, and

others, eulogised in the local guides, pre.sent any thing in

the Avay of our art particularly deserving of notice ; though

their situations, looking doAvn on so magnificent a lake, the

simplicity of their architecture, and the romantic scenery by

Avliich they are sun-ounded, render them delightful retirements,

and such as but fcAV countries can lioast. The

villa-gardcns excel in rustic buildings ( fg . 12 1.) and

arbours ; and avc, for the most part, a mixture of orchards

ou hilly surfaces, cultiA'ated spots, and rocks. IIoAvever

insignificant such grounds may look on paper ( fg . 122.), in the reality they are

j^22 i>lcasing and romantic.

Tho public

promenades at Berne

arc most beautiful,

and kept witli all the

care of an English

flower-garden. In

the capitals of the

other cantons, public

gardens arc cither

of much smaller extent,

or altogether

AA-anting. Indeed, in

a country abounding

ill picturesque

sccnciy, and common

pastures, and

parochial forests,

limited spaces for

recreation arc altogether uncalled for. Who that is free to climb the rocks, or the

gras,sy steeps, or oven to Avalk along thé liigliAvays, in such a country, Avonld desire to

bo confined to enclosures iu or about tOAvns ? Switzerland has the ¡leculiar advantage

of producing a close turf, Avliich, in most places, and particularly at Lausanne and

Berne, is as verdant as in England. Harte says that great part of the Bays dc Vaud

is like the best part of Berkshire ; and, indeed, CA'Ciy one feels that this is tlie countiy

most congenial to au Englishman’s taste and feelings.

411. Ferney. The grounds arc laid out in varied walks, like an English pleasure-

ground, very ample, and well planted. From the terrace, in front of the house ( fg . 123.),

123

the lake of Geneva is seen at a distance of three or four miles; mid beyond, Mount

Blanc, with otlicr hills, making a very grand termination to the vicAv. The situation,

which is delightful, has, nevertheless, one great abatement, the total Avaiit of Avnter, Avhicb,

for every domestic purpose, is brought three miles. Snmmcr-seats and boAvcrs, Avlierc