gardens of this sort conld or could not be introduced, Ave Avould commence near the house

an arboretum, scattering the trees thinly over each side of the Avalk among the other

trees aud slirubs, or on the laAvn, and so an*anging them as to extend over the whole

length of the walk, Avhether that Avere half a furlong or two or three miles, taking care

that every tree and shinib that formed a part of the arboretum Avas completely detached,

so as to afford ample room for its growth and natural shape. We Avould also have every

plant named. Where the shi-ubbery or pleasure-ground Avas not hu-ge enough to admit

of a complete ai-borctum, Ave would introduce only as many species as could be Avell

groAvn; and, even if that number did not amount to a hundred, it might include one

species of most of the genera Avliich constitute the British ai-boretum.

1591. As general principles fo r planning cottages, though the comfort and convenience

of the inhabitants sliould be made the primary consideration, the manner in Avhich they

hai-monise Avith the stylo of the mansion or villa to Avhich they form an appendage, should

be ahvays considered, as a Avant of liai-mony in these particulars often spoils the

general effect of an othei'Avise Avell an-anged place, and renders a cottage a deformity

instead of making it form an ornamental part of the Avhole. Tlicre are few things,

indeed, in landscape-gardening that require greater skill on the part of the artist than

the management of cottages ; but Avhcn they ai-e properly managed, they may be rendered

highly ornamental, and they give an ah- of comfort and habitation to the whole.

Sect. II. PuUic Gardens.

1592. Public gardens are designed for recreation, instruction, or commercial purposes.

The first include equestrian and pedestrian promenades; the second, botanic and experimental

gard en s; and the third, public nm-series, mai-ket-gardcns, florists’ gardens,

orchards, secd-gardens, and herb-gardcns.

Subsect. 1. Public Gardens fo r Recreation.

1593. Public parks, or equesti'ian promenades, are valuable appendages to large cities.

Extent and a free air are the principal requisites, and the roads sliould be an-anged so as

to produce few intersections; but at the same time so as carriages may make either the

tour of the Avhole scene, or adopt a shorter toiu- at pleasure. In the course of long roads,

there ought to be occasional bays or side expansions, to admit of cai-riages separating fi-om

the course, halting, or turning. Wliere sucli promenades are very extensive, they should

be furnished with places of accommodation and refreshment, both for men and horses;

and this is a valuable part of thcir arrangement for occasional visiters from a distance,

or in hired vehicles. Our continental neighbours have hitherto greatly excelled us in

this department of gardening ; almost every tOAvn of consequence having its promenades

for the citizens á cheval and also au pied. Till tlie commencement of the nineteenth

century, Hyde Park, London, and a spot called the Meadows, near Edinburgh, were the

only equestrian gardens in Britain ; but in 1810 the Regent’s P a rk was commenced fi-om

a suggestion of WiUiam Fordyce, Esq., the then Surveyor of Woods and Forests, and it

has now become a scene worthy of tlie metropolis. Since that period a great many

parks and pleasure-grounds have been laid out in different parts of the suburbs of the

metropolis, aud other gardens of a similar nature have been foi-med in vai-ious parts of

Great Britain.

1594. Boulevards (Boulevard,'Ey., or round w o rk ; a bulwark, or great bastion, or

rampart, generally round). Many of the continental cities have a species of etjuestrian

promenade Avithin their boundaries, which is deserving of imitation. These are broad

roads, accompanied by rows of trees, near the mai-gin of the city, originally foi-med on

the ramparts, or sun-ounding fortifications, and completely encircling it. They are

highly interesting promenades, especially to a stranger, to Avhom they give an idea of

the topography and most remarkable points of the scene in the most agreeable manner.

The boulevards at Paris, Vienna, and Moscow, are particularly to be admired in these

respects.

1595. Public gardens, or pedestrian promenades. These, with very feiv exceptions,

have been in all ages and countries laid out in the geometric style. The Academus at

Athens is an ancient example; and the summcr-garden at St. Petersburgh a modern

o n e ; and however much English gardening has been praised and copied by private

persons on the continent of Europe, yet, with tbe exception of the English garden at

Munich, that of Magdeburg, and a few others, the rest are very properly in straight

lines. The object of public gardens is less to display beautiful scenery than to afford a

free wholesome air, and an ample unintemipted promenade, cool and shaded in summer,

and Avarm and sheltered in spring and winter. In a limited extent, the combination of

these objects must be attempted in one principal Avalk, Avhich, for that purpose, should

as much as possible be laid out in a north and south direction. In more extensive scenes,

covered Avalks may be devoted to summer, and cast and Avest open Avalks, to spring and

winter. The broad open and naiTow covered avenues of the ancient style are valuable

resources on a large scale ; these conjoined, and laid out in a south and north direction,

give in the centre an open, sheltered, sunshine walk in m idw in te r a n d a close or covered

avenue being laid out along each side of the open central one, Avill afford shady walks

for summer and occasional places of retreat from casual showers in spring. Oxford and

Cambridge afford some fine open and covered avenues, though far inferior to many on

the Continent. .

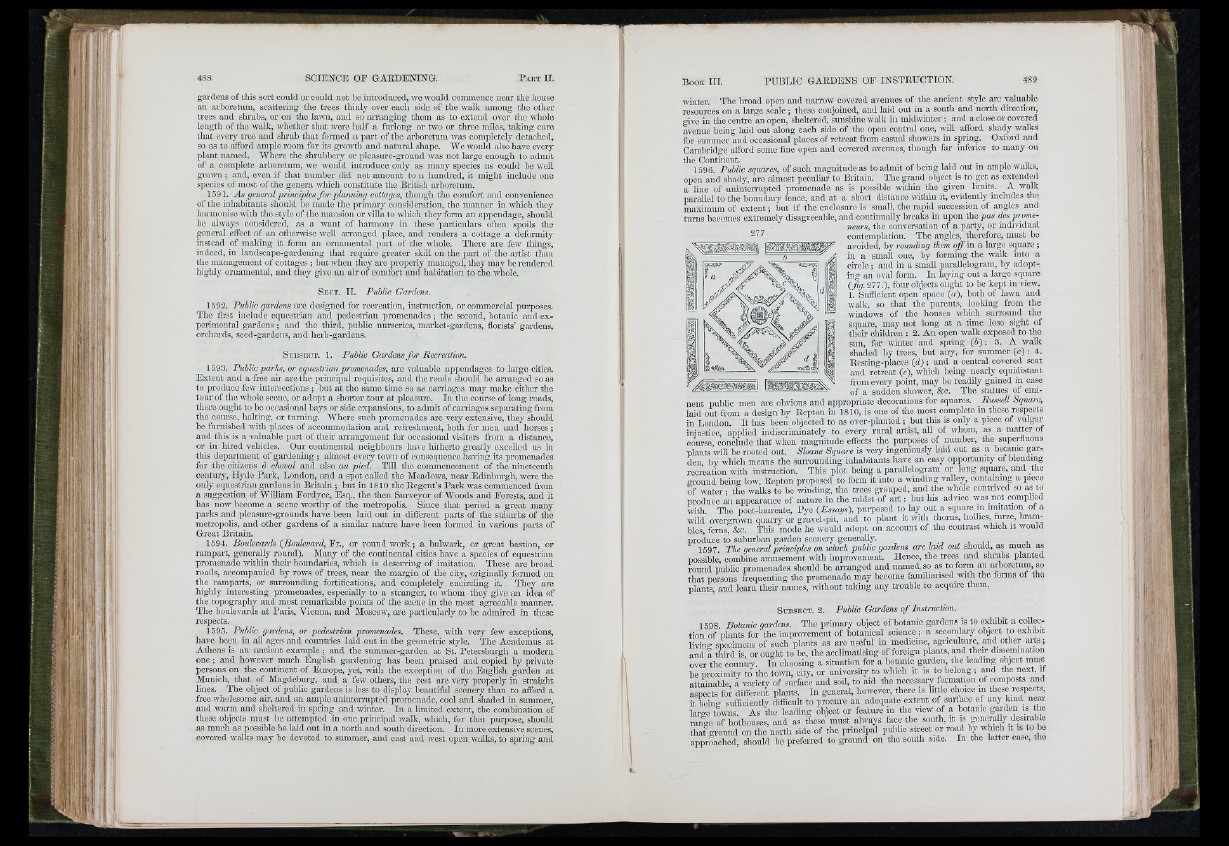

1596. Public squares, of such magnitude as to admit of being laid out in ample walks,

open and shady, are almost peculiar to Britain. The ^-and object is to get as extended

a line of uninten-upted promenade as is possible within the given limits. A walk

parallel to the boundary fence, and at a short distance within it, evidently includes the

maximum of ex te n t; but if the enclosure is small, the rapid succession of angles and

turns becomes extremely disagreeable, and continually breaks in upon the pas des promeneurs,

277

the conversation of a party, or individual

contemplation. The angles, therefore, must be

avoided, by rounding them o ff in a large square ;

in a small one, by forming the walk into a

circle; and in a small parallelogram, by adopting

an oval form. In laying out a largo square

(fig. 277.), four objects ought to be kept in vieAV.

1, Sufficient open space (a), both of laAvn and

Avalk, so that the parents, looking from the

windows of the liouses Avhich smround the

square, may not long at a time lose sight of

tlieir children : 2. An open Avalk exposed to the

sun, for winter and spring (b) : 3. A Avalk

shaded by trees, but airy, for summer (c) ; 4.

Resting-places (d) ; and a central covered seat

and retreat (e), which being nearly equidistant

from evei-y point, may be readily gained in case

of a sudden shower, &c. The statues of eminent

public men arc obvious and appropriate decorations for squares. Russell Square,

laid out fi-om a design by Repton in 1810, is one of the most complete in these respects

in London. It has been objected to as over-planted ; but this is only a piece of Amlgar

iniustiee, applied indiscriminately to every rural artist, all of Avhom, as a matter ot

course, conclude that Avhen magnitude effects the pui-poses of number, the superfluous

plants will be rooted out. Sloane Square is very ingeniously laid out as a botanic garden,

by Avhich means the siuTounding inhabitants have an easy opportunity of blending

recreation with instruction. This plot being a parallelogram or long square, and the

ground being low, Repton proposed to form it into a Avindmg valley, containing a piece

of w a te r: the walks to be winding, the trees grouped, and the Avhole contrived so as to

produce an appearance of nature in the midst of a r t : but his advice Avas not complied

Avith. The poet-laureate, Pye (Essatjs), purposed to lay out a square in imitation ot a

wild overgrown quaivy or gravel-pit, and to plant it Avith thorns, hollies, furze, brambles,

ferns, &c. This mode he would, adopt on account of the contrast Avhich it Avould

produce to suburban garden scenery generaUy.

1597. The general principles on which puhlic gardens are laid out should, as much as

possible, combine amusement Avith improvement. Hence, the trees and shnibs planted

round public promenades should be an-angcd and named so as to form an arboretum so

that persons frequenting the promenade may become familiansed with the forms of the

plants, and learn thefr names, without taking any trouble to acqiurc them.

Subsect. 2. Public Gardens o f Instruction.

1598 Botanu: gardens. The primary object of botanic gm'dcns is to erMbit a collection

of plants for the improyement of botanical science; a secondary object to exhibit

livino- specimens of such plants as arc useful in medicine, agriculture, and other a rts;

and a third is, or ought to be, the acclimatising of foreign plants, and their dissemination

over the country. In choosing a situation for a botanic gai'den the leading object must

be proximity to the town, city, or university to which it is to belong; arid the next, it

attffinable, a variety of surface and soil, to aid tho necessai-y formation of composts and

aspects for different plants. In general, however, there is litfle choice m these respects,

it being sufficiently diflicult to procm'e an adequate extent of surfece of any kind neai

largo tmvns. As the leading object or feature in the view of a botanie garden is the

range of hothouses, and as these must alw-ays face the south, it is generally desirable

that ground on the north side of the principal pifelio street or road by which it is to be

approached, should he prefeirecl to ground on the south side. In the lattei case, the