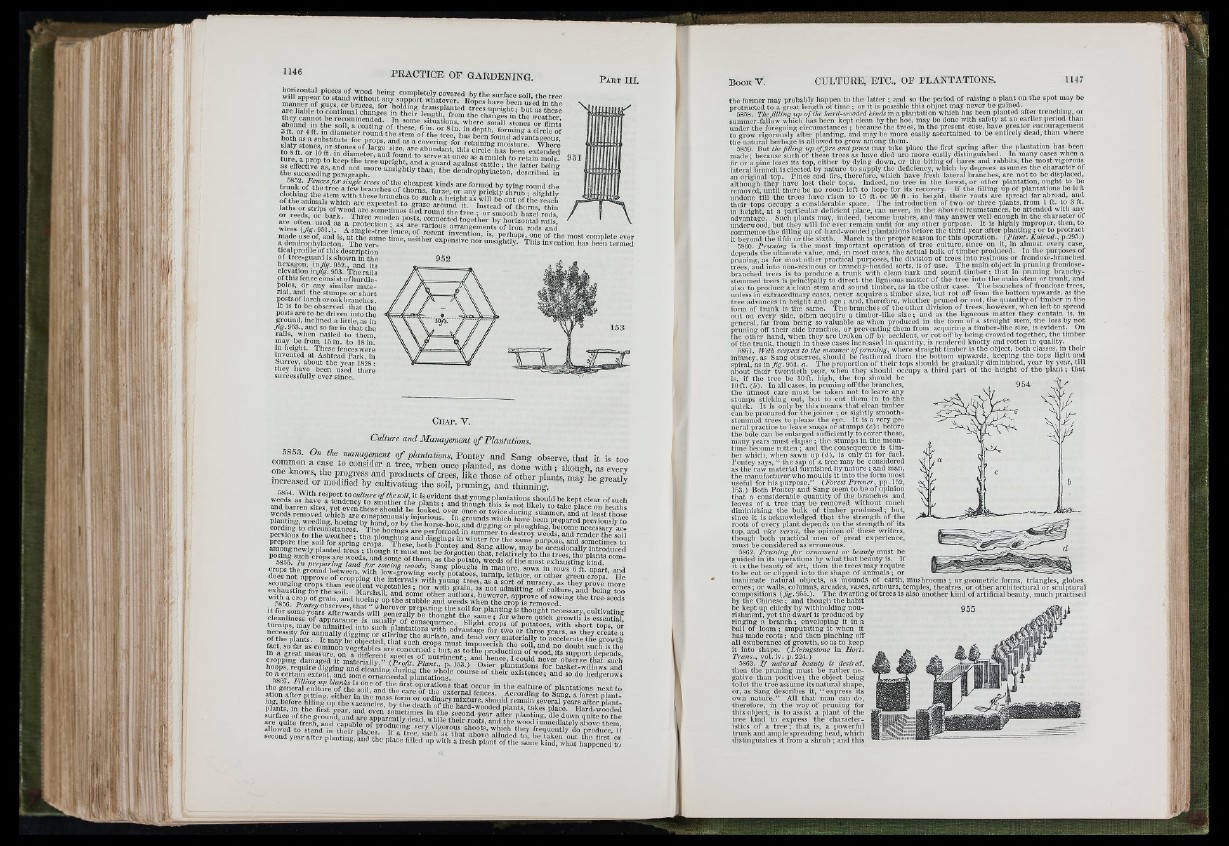

made use of, anti is, a t the same tim “ idthYr“ ? p SY » ”c']™’m s iE h u ¥ ’’V ^ the most complete ever

a dendrophylacton. The ver- expensive nor unsightly. This invention has been termed

tical profile o fth is description

of tree-guard is shown in the

hexagon, in fig . 952., and its

elevation infig. 953. Therails

o f this fence consist of hurdle-

polos, or any similar material,

and the stumps or short

posts of larch or oak branches.

It IS to be observed that the

posts are to be driven into the

ground, inclined a little, as in

fig . 953., and so far in th a t the

rails, when nailed to them,

may be from 15 in. to 18 in.

in height. These fenceswere

invented a t Ashtead Park, in

Surrey, about th e year 1828-

they have been used there

successfullj- ever since.

C h a p . V .

Culture and

S8S3. On the management o f plantations, Pontey and Sanjr observe that it is t™,

common a case to consider a tree, when ontoe planted, as Sonf wfrhTthoLfi as e v L

weeds removed which are conspicuouslv injurious In grefends whfoh x L least those

planting, weeding, hoeing by hafed, or by tlie h ™se hoe f f dftLfo? ?? ¡¡f fe®®" Pjepared previously to

cording to circumstances The Imeinsi a r t nLfnrmfed or ploughing, become necessary a c

pervious to the weather ; the ploughing and d i g S s l n f f teFfrfe re fe tl ''’®® ’ »"‘I ‘he soil

prepare the soil for snring crons The?.» hefh%Afef? ] r® ior the same purpose, and sometimes to

hoops, require digging and HeLiTiD' k?,' plantations for basket-willows and

"ta “'"■ta

th e general'oTltTre i f l * »ra"„tadYhetaS^^^^^^ ” Y ' » ' P hhtatious next to

tacoud vear aKer p la n tin g S S 'tfm

the former may probably happen to tho latter ; and so the period of raising a p lant on the spot may be

nrotractod to a great length of time ; or it is possible this object may never be gained.

5858 The filling up of ihe hard-wooded kinds in ap\ani.alion which has been planted after trenching, or

summer-fallow which has been kept clean by the hoe, may be done with safety a t an earlier period than

under the foregoing circumstances ; because the trees, in the present case, have greater encouragement

to grow vigorously after planting, and may be more easily ascertained to be entirely dead, than where

tho natural herbage is allowed to grow among them. _ , . v t

5859. But the filling up of firs and pines may take place th e first spring after th e plantation has been

m ad e : because such of these trees as have died are more easily distinguished. In many cases when a

lir or a pine loses its top, either by dying down, or the biting of hares and rabbits, the most vigorous

lateral branch is elected by nature to supply the deficiency, which by degrees assumes the character of

an original top. Pines and firs, therefore, which have fresh lateral branches, are not to be displaced,

although they have lost their tops. Indeed.no tree in the forest, or other plantation, ought to be

removed, until there be no room left to hope for its recovery. If the filling up of plantations be lelt

undone till the trees have risen to 15 ft. or 20 ft. in height, their roots are spread far abroad, and

thcir tops occupy a considerable space. T h e introduction of two or three plants, from 1 ft. to 3 ft.

in height, a t a particular deficient place, can never, in the above circumstances, be attended with any

advantage. Such plants may, indeed, become bushes, and may answer well enough in the character ot

underwood but they will for ever remain unfit for any other purpose. It is highly improper, then, to

commence the filling up of hard-wooded plantations before the third year after p lan tin g ; or to protract

it beyond the fifth or the sixth. March is the proper season for this operation. {Plant. Kalend., p.295.)

58C0. Pruning is the most important operation of tree culture, since on it, m almost every case,

depends the ultimate value, and, in most cases, th e actual bulk of timber produced. In the purposes of

pruning, as for most other practical purposes, th e division of trees into resinous or frondose-branched

trees and into non-resinous or branchy-headed sorts, is of use. The main object in pruning frondose-

branched trees is to produce a tru n k with clean bark and sound timbe r; th at m pruning brmichy-

stemmed trees is principally to direct the ligneous m atter of the tree mto the mam stem or trunk, and

also to produce a clean stem and sound timber, as in the other case. The branches of frondose trees,

unless in extraordinary cases, never acquire a timber size, but rot off from the bottom upwards, as the

tree advances in height and age ; and, therefore, whether pruned or not, the quantity ot timber in the

form of trunk is th e same. The branches of the other division of trees, however, when left to spread

out on every side, often acquire a timber-like size; and as the ligneous matter they contain is, in

general, far from being so valuable as when produced in the form of a straight stem, the loss by not

pruning off their side branches, or preventing them from acquiring a timber-like size, is evident. On

the other hand, when they are broken off by accident, or ro t off by being crowded together, tlm timber

of the trunk, though in these cases increased in quantity, is rendered knotty and rotten in quality.

58G1. With respect to the manner qf pruning, where straight timber is the object, both classes, in their

infancy, as Sang observes, should be feathered from the bottom upwards, keeping th e tops light and

spiral, as in fig 95i. a. The proportion of their tops should be gradually diminished, year by year, till

about their twentieth year, when they should occupy a third part of the height of th e p la n t; that

is, if the tree be 30 ft. high, the top should be

10 ft. ( i ) . In all cases, in pruning off the branches,

the utmost care must be taken not to leave any

stumps sticking out, but to cut them in to the

quick. It is only by this means th at clean timber

can be procured for the joiner ; or sightly smoothstemmed

trees to please th e eye. It is a very general

practice to leave snags or stumps ( c ) : before

th e bole can be enlarged sufficiently to cover these,

many years must elapse ; th e stumps in the meantime

become rotten ; and the consequence is tim ber

which, when sawn up (d), is only fit for fuel.

Pontev says, “ the sap of a tree may be considered

as the’raw material furnished by nature ; and man,

th e manufacturer who moulds it into the form most

useful for his purpose.” {Forest Prunei', pp. 152,

153.) Both Pontey and Sang seem to be of opinion

that a considerable quantity of the branches and

leaves of a tree may be removed without much

diminishing the bulk of timber produc ed; but,

since it is acknowledged th at the strength of the

roots of every plant depends on th e strength of its

top, and vice versil, the opinion of these writers,

though both practical men of great experience,

must be considered as erroneous.

•5862. Pruning fo r ornament or heauty vnnsX be

guided in its operations by what that beauty is. If

it is th e beauty of art, then the trees may require

to be cut or clipped into the shape of animals ; or

inanimate natural objects, as mounds of earth, mushrooms ; or geometric forms, triangles, globes,

cones ; or walls, columns, arcades, vases, arbours, temples, theatres, or other architectura! or sculptural

compositions { fig . 955.). 7'he dwarfing of trees is also another kind of artificial beauty, much practised

by th e Chinese ; and though the habit

be kept up chiefly by withholding nourishment,

yet the dwarf is produced by

ringing a branch ; enveloping it in a

ball of loam ; amputating it when it

has made ro o ts ; and then pinching off

all exuberance of growth, so as to keep

it into shape. {Livingstone in Hort.

Trans., vol.iv. p .224.)

5863. Xf natural beauty is desired,

then the pruning must be ra the r negative

than positive; th eo b je c t being

to let th e tree assume its natural shape,

or, as Sang describes it, “ express its

own n atu re .” All that man can do,

therefore, in the Avay of pruning for

this object, is to assist a plant of the

tree kind to express th e characteristics

of a tre e ; th at is, a powerful

tru n k and ample spreading head, which

distinguishes it from a shrub ; and this

l i j