can be proa ired, in order to produce variety, observes, that “ variety, of which the true end i« r,. r«i5o,».,

Î f t fe’ not consist in the diversity of sepanite objects, but n the ditersltv M

their effects when combined togeth»r,so as to form a différence of composition and c h a îL t e r K

Uiiiik, however that they have obtained th at grand object, when they have exWbited in one bod^ aH th è

Mard names of the Linnæan system ; but when as many p ants as cah bEwelJ got t S ^ h e F L v r ^

m every shrubbery, or in every plantation, the result is^aLameiiess of r d i ïÏ Ï e n rkM d Mft m,t leT

a sameness th at would arise from there being no diversity at all : for there is n o ’having varipL ,ir

" ‘"'""ta ta -‘„ e s o ]Y M c r th ‘r é ; r é c .Y a .Y

By this mdiscnmuufte mixture of every kind of tree in planting, all variety is ¡ S o L S hv

ot vai lety, whether it is adopted m belts, or clumps, as they have been technically called • for examnle

lumps be composed i f ten differint S or"t£;t'troo7ii S to p t * r b e £ £ £ i m C

, but if each chimp consists of a distinct kind of tree, they become ten different tilings of wh ici

ilar f t " sorts iff rrees in pnr-h th.ir KqLLT A 1

one may hereafter furnish a group of oaks, another of elms, another of chestnuts or of thorns &c

hire mannty m the modern belt, the recurrence and monotony of the same mixture of trees of al

diffci-ent kinds through a long drive, make it th e more ted ioL in proportion L is o n ?

th e drive at Woburn, m wliich evergreens alone prevail, which is a circimstafecfof gfandim

of novrity, and, I may add, oi winter comfort, that I never saw adopted in any other place ’on s’oTnfe

iificent a scale the contrast ot passing from a wood of deciduous trees to a wood of evergreens must 1

elt by the most heedless observer : anH m>p . r pleasure, though m a w T k e r degree w™ Id U

all the

In part of

r IX , X, : ■— ------ i.rt„„x..f, HOT.IXX <i »vuuu Ul ucuiiiuuuB Liets lO H WOOfI ot pvprgr

fe t he«Iless ;and the same sort of 'in weaker decree would he

ihpLLwpfefo?® T ftfe of different kinds grofefef ’

themselves, instead of being blended indiscriminately.” ^

•J3-H. Chambers and Price agree in recommending the i'

As were collected in small groups or masses by

(Inquiry info Changes of Taste, &c., p. 33.)

mitation of n ate ral forests in the arrangement

■lecies. In these, nature disseminates lier plants 1

he parent m masses or breadths, depending on i

. which these seeds afford for being carried to a d.Bb<u.uu u , luu w.u«. me ram anct Dy Dirds or

animal^ So disseminated they spring up, different sorts together, affected by various circum

:es ot.soil .and situation ; and arrive at maturity, contending with other nl.ants .“L ffeL

o fth e sp e c ie s.In ty ese ,natu're dissemhmtes lrer‘‘V l aM s ? r s c X . ^

tiyo

by

depending on a variety of circunistaimes, but chiefly on the Vl Q XVro_________ , , • 1

of surface, ¿II, circumstances changing in favour of some other species, that takes the prevalence in ¡t<

turn. In this way it will generally be found, that the number of species, and the extent and stvle o fth e

masses m which they prevail, bear a strict analogy to the changes of soil aiul suíf™T™ud this

Td’L L respect to trees and shrubs, but to plants, grasses, and even the mossy tribe.

5842. The most perfect arrangement of species in regard to varietv

would_be to employ every kind of tree and shrub th at will grow

fre ^ y in the open air, and arrange them according to the natural

system. _We have already suggested that a residence might be

wooded m this way, so as in th e smallest extent to obtain a maximum

of variety and beauty. In most cases, where grouping, or

any systematic plan of arranging tho species, is to be adopted, the

torm of the groups (/g.94!). «, b, c, d, e) should be marked on the

plan of tiie plantation, and the kinds for each form written down in

a corresponding listy the small detached masses intended as thickets

( / ) should be similarly marked, th e situation of groups indicated

either by letters simply (g), or by figures (6, 2. 3) referring to a list

ot kinds ; and where shrubs are to be introduced in the groups, two

figures may be used ( f , 4), one of which shall indicate the kind of

tree , and the other the species of low growth or shrub. This mode

we have always adopted in furnishing plans for ornamental planting,

aud tind it enables gardeners to execute them with periect

accuracy.

5843. The size o f theplants used in ornamental planting should

be as large as the soil and situation will admit, for two re asons: flr.st, because an early effect is always

desirable; and, secondly, because, m planting detached groups, large and small plants and a varied

mriination ot their stems (fig. i)48.) may be introduced in imitation of nature. Small groups on pa--

Uired lands, indeed, cannot be formed without trees whose stems are sullicicntlv high to raise their

heads out o fth e re ad i of cattle, without enclosing so considerable a space round every tree as o re

this mode a t once tedious, unsightly, and expensive. .y to iciuu.r

5844. The retnoval of large trees, with their heads and branches entire, has latelv engaged a good deal

consequence of a work published on the subject, by Sir'llen ry «Steuart. The

practice is of considerable antiquity, having been well known, in England, in Evelyn’s time and in

1 f e f ? ?• T h e mode of operation is to cut a trc n c h round the tree intended to

be rtrnoved, a t the distance ol 6ft. or 8 ft. or more trom the trunk, according to the size of tho tree • a

year after which the tree is removed with its head entire. This trench was, by tlie early practitionLs

refeLÍlTLfo' f Stouart, filled up with fine mould, to encourage th e production of fibres from

the extn.mitics of the roots, during the twelve months which elapsed between the cutting of the trench

®i are generally much injured in removal, some eminent

practical men. such as M Nab, of the Edinburgh Botanic Garden, and Munro, of th e Brechin nursery

couBider theiv production in the mould of tho trench as of but little use, believing that the grand obiect

?>, y r® r ?y th« raots of tke tree is that of stunting its growth, and preparing it, by a previous

check, for the stiil greater ch«;k of remo v a l; this cutting round being in both both cases cases pei-performed foVmed a a re year

a r

tho Quarter ' c

-ro-- ------- ,OT.J J.....OTXXXOTOT „X.. .<xL,u..o UU this subject will be found in

J o vol. ix. p. 21

Ai u r n ,a l . - ffsrtc u llu re, vol. ii. p. 823., and Mr. Munro’s in the Gardener’s Magazine.

„QQ,. Q, rt. rt .fe" ®." .ft® iiclvantage, in a pliysiological point o ‘‘view, of keening the

rt «"tire ; but, in our opinion, the advantages of this practice havo been greatiy overrated

T ?® - P?® ft® ?«®chTnd one or two others, no advaM-^e

rvnnrfefeLf ‘'’PI'®'"'» be gaiiiccl. This m ay b e proved by trying an

experiment on two trees ol the same kind, age, and size, and, indeed, in all respects similarly circum-

rianccd. Cut round the roots of both trees at the same distance from the stem ; and, after these trees

have stood ii y«ir m that situation, lop off the entire head of the one, and leave untouolied the head of

life "ft®''? be then removed with equal care, and to equally favourable situations, the

lopped tree will, in a very few years, attain th e size of the other. This result is consistent with the

f f® re®'T e'Yfe®"®'' attended to the subject, and with the practice of transplanting

laige trees for th e roadsides, common on the Continent. In transplanting orange trees, in the neigh?

¡reincr®? ? Genoa the same mode is pursued. ^Suppose the stem of the tree to be 1 in. in dimater, the

ff e nv r n r cut off about 6 m. from the stem ; ancl th e stem itself is cut over at the height of 4 ft.,

5 ft., Ol 6 ft. from the ground. The fibres, m this last case, as in those of all tho others above men-

T i / f f be so withered by the taking up of tlie tree, as to have lost their functTons,

mM icno?ii?st?q.u»cn ce orf ’rtih e accu"m ®u FlafteeLd sap® anft,d® vfei®ta®l energyd ecpoenncde nentrtaitreedly i no nt hiets mpoaiwne rro ooft ss eannddi ntrgu onukt. fibres

5845. The main advantage o f transplanting trees with their heads entire, is th at of producing an

immediate effect; and, when this is desired, we are of opinion tb at the practice recommended by

M‘Nab and Munro, is preferable to th a t practised by Lord Fitz-Harding, and revived by Sir Henry

Steuart.

5846. Where large trees are required for groups in a park, or for thickets, or plantations, to produce

a speedy effect, we would recommend cutting round the roots a year before removal; leaving the trench

open a whole summer ; removmg the tree the foUowing wiuter, so as to injure th e fibres formed within

the bail of earth as little as possible, and either shortening in all the branches of the head, or lopping

them off entirely, according to circumstances. If the trees to be removed were not of very large size

or of kinds which are difficult to transplant, we should not require the roots to be cut round a year

before; we would, in such a case, take them at once from where they s to o d ; preserving as great a

length as possible of ramose roots, and cutting off entirely, or severely shortening in, the branches, or

head. If planted in suitable soil, we should have no fear of their success. The saving of expense hy

this mode of transplanting large trees must obviously be very considerable; but what is not quite so

obvious is, that the saving of life wouid probably be still greater. In all climates, not naturally moist,

it is hardly possible that a large tree, removed with its head entire, can withstand the heat and evaporation

of the lirst succeeding summer ; and, accordingly, we find that a large portion of transplanted

trees of this description linger and die. This, we are informed, has been the case even in the moist

climate of Allanten, and under the immediate care of Sir Henry Steuart. Two other causes are very

unfavourable to the durability of trees transplanted when they are of a large size: the first of these

causes is the supplying the newly-transplanted trees with too rich food by means of the composts made

to insure tlieir growth ; which treatment throws the sap of the tree into avi unnatural state, producing a

disease which we may suppose is something analogous to what in animals is called a su rfeit; the second

cause is making choice of trees too old for the increased action required. (See M'Nub, iu Quarterly

Journal o f Agriculture, and Gorrie in Gardener’s Magazine, vol. vi. p. 43., and Sinclair, Ibid., vol. iv

p. 336.)

5847. Various machines for aiding in the removal of large trees will be found figured or described from

§ 1912. to § 1916.; also in the Encyc. o f Agr., 2d edit. § 3937.

5848. Fences. Masses, in the ancient style of planting, were generally surrounded by walls or other

durable fences. Here the barrier was considered as an object, or permanent part of the scene, and for

th at reason was executed substantially, and even ornamentally. It generally consisted of walls architecturally

finished, and furnished with handsome gates and piers. The vows of avenues, and small

clumps or platoons, intended to be finally thrown open, were enclosed by the most convenient temporary

fence.

6849. In planting in the natural style, a regular fence, either of verdant or masonic materials, can never

be the final part ol perfect imitation, since no such thing is to be found in nature. But in planting in

farm-lands, or for tlie purpose of improving the general scenery, some permanent fence is requisite ;

and all that can be said is, that which promises in the end to be the most efficient and economical, will

almost always be the bcst. The hedge, sunk fence, common wall, and wide watercourse where it will be

con.stantly nearly full of water, here present themselves as the most general kinds. Any fence, however,

of which a large excavation, without water, forms a part, as the sunk fence, should be used with great

caution ; as there are none of this class but what look ill from a t least one point of view, that is, when

seen lengthwise.

5850. I n planting to fo rm a park or residence, with the exception of the boundary fence, and th at which

separates the lawn or mown surface from the grazed scenery, no permanent barrier of a formal nature

should ever be admitted. In very bleak situations, walls or mounds of earth, however unsightly, maybe

necessary for a time to shelter and draw up the plants ; but the final removal of these, aud all fences in

parks, should be looked to as certain. Light palings, the rails coated over with ta r or pyroligneous acid,

and the posts charred by burning ;it the lower end, to render them durable, may be used in the greater

number of cases ; and in many, where the plants are larger, and the soil and other circumstances favourable

to their growth, hurdles, or other movable rails or palings, may be used. “ The present improved

state of the manufacture of iron offers a very desirable accommodation in this respect, affording the best

guards for single plants and groups ; and iron hurdles, or lines of cast-iron standards and half-inch wir

as rails for masses, have a light and temporary appearance, highly congenial to the idea of their spec

removal. The lines of the fences conforming to the iriegiilar shapes of tiie masses will not be disagreeable

to the eye, if those of the latter ave arranged with any regard to apparent connection ; for any objects,

whether lines or forms, however deficient in beauty of themselves, acquire a degree of interest, and

even character, when connected and arranged in such a way as to form a whole. 'Wheii a plantation is

finally to be composed both of trees and undcrgrowths, thorns, sloes, hollies, berberries, and briars may,

ill many cases, prevail in the margin ; which, when the fence is removed, will form a picturesque phalanx,

and protect the whole. P artial inroads, formed by cattle, will only heighten the variety aud intricacy of

such masses.” (Edin. Encyc., art. Landscape-Gardening.) In this wav, as Trice observes (Essays, vol. i.),

the planter may plant as thickly as he chooses, and never think of thinning or future management, only

taking care to introduce no more trees than what he intends to remain finally as timber. 'J'he great

majority of the plants, being shrubs, will soon be overtopped by the timber trees, which, having abundance

of head-room, will grow up in free and unconstrained shapes. 7’he future care of plantations is

so geuerally neglected, th a t this suggestion, under certain circumstances, well merits adoption ; though

It cc-rtainly can have no pretension to be called a scientific or profitable mode of planting : it is, what it

pretends to be, a picturesque mode.

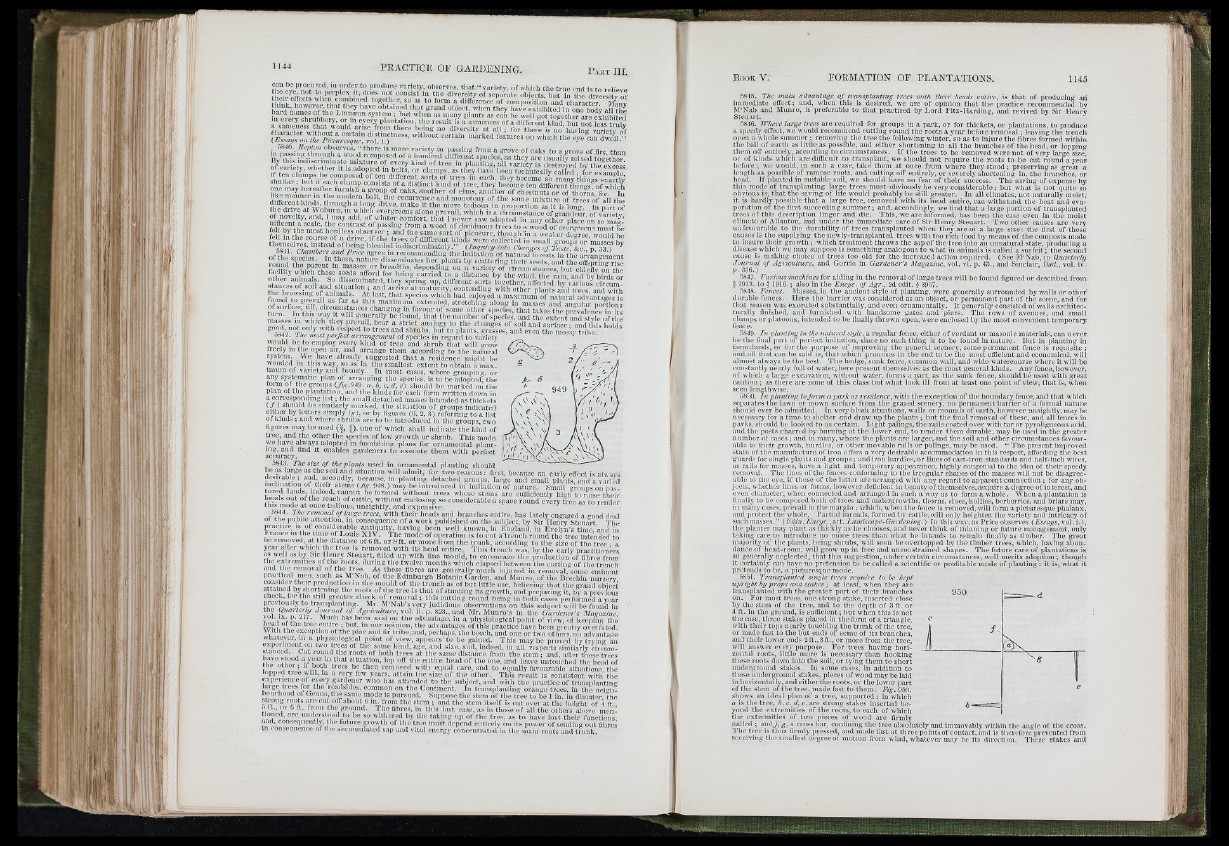

58.51. Transplanted single trees require to be kept

upright by props und stakes ; a t least, when they are

transplanted with the greater part of their branches

on. For most trees, one strong stake, inserted close

by the stem of the tree, and to the depth of 3 ft. or

4 ft. in the ground, is sufficient; but when this is not

the case, three stakes placed in the form of a triangle,

with their tops nearly touching the trunk of the tree,

or made fast to the but ends of some of its branches,

and their lower ends 2ft.,3ft., or more from the tree,

wil) answer every purpose. For trees having horizontal

roots, little more is necessary than hooking

these roots down into the soil, or tying them to short

underground stakes. In some cases, in addition to

these underground stakes, pieces of wood may be laid

in horizontally, and either the roots, ov the lower part

of the stem of the tree, made fast to them. Fig. 950.

shows an ideal plan of a tree, supported; in which

a is the tree, b, c, d, e, are strong stakes insertod beyond

the extremities of the roots, to each of which

tlie extremities of two pieces of wood are firmly

9 5 0

J '■

1 '

c

oi ot nailed ; a n d /, g,r, a cross bar, confining the tree absoli....^absolutely and .............. immovably ....... ....

within the angle of the c

I he tree is thus s firmly pressed, aiid^and made last at three points of contact, and is thcrcfore°therefore prevented preventcd from

.....

receiving the smallest degreeot motion from wind, whatever mav be its direction. These stakes and

Í..

A.