A R T O F G A R D E N IN G .

are called joints, or at tliose parts where leaves or buds already exist. Hence it is that

cuttings ought always to be cut across, with the smoothest aud soundest section possible,

at an eye or joint : and as buds arc in a more advanced state in wood somewhat ripened,

or fully fonncd, tlian in that which is still in a state of formation, this section ought to

be made in the wood of the growth of the preceding season, or as it were in tlie point

between the two growths. It is true that there arc many sorts of cuttings, which not

only throw out roots from tlie ring of granulated matter, but also from the sides of every

pai-t of the stem inserted in the soil, whether old and large (c), or young and small (d e),

as willows, cun-ants, vines, &c. ; but as all plants which are difficult to root, as lieatlis (/),

camelhas, orange-trees, &c., will be found in the first instance, and for several years after

propagation, to throw out roots only from the ring of herbaceous matter above mentioned,

to facilitate the formation of this ring, by properly preparing the cuttings of

even willows and currants, must be an obvious advantage. It is a common practice to

cut off the whole or a part of the leaves of cuttings ; but the former is always attended

with bad effects, as the leaves may be said to supply nourishment to the cutting till it

can sustain itself. This is very obvious in the case of striking from buds (g ), which,

without a leaf attaciied, speedily rot and die. Leaves alone, as in Bryophyllum calyci-

iium, will even strike root and form plants in some instances; aud the same, as Professor

Thouin observes, may be stated of certain flowers and fmits.

2496. C u ttin g s lohich are d iffic u lt to s trik e may be rendered, more tractable by previous

ringing ; if a ring be made on the shoot which is to furnish the cutting, a Cidlus will

be created, which, if inserted in the ground after the cutting is taken off, will freely emit

roots. A ligature would perhaps operate in a similar manner, though not so efficiently;

it should lightly encircle the shoot destined for a cutting, and the latter should be taken

off Avheu an accumulation of sap has apparently been produced. The amputation in

the case of the ligature, as well as in that of the ring, must be made below the circles,

and the cutting must be so planted as to have the callus covered with earth. (H o rt.

T ra n s ., vol. iv. p. 558.)

2497. T h e insertion o f the cuttings may seem au easy matter, and none but a practical

cultivator would imagine that there could be any difference in the gi’owtli between cuttings

inserted in the middle of a pot, and those inserted at its sides. Yet such is actually

the case; and some sorts of trees, as the orange, Ccratonia, &c., if inserted in a mere mass

of earth, will hai'dly, if at all, throw out roots ; ivliilc, if they are inserted in sand, or in

earth at the sides of the pots, so as to touch the pot in thcir whole length, they seldom

fail of becoming rooted plants. Knight found the mulberry strike vciy well by cuttings,

when they were so inserted, and when their lowcr ends touched a stratum of gravel or

broken pots; and Hawkins (H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. ii. p. 12.), who had often tried to strike

orange-trees, without success, at last heai'd of a method (long known to nurserymen,

but which was re-discovered by Luscome,) by wliich, at the first trial, eleven cuttings

out of thirteen grew. “ The art is, to place tlieni to touch the bottom of the pot ; tliey

arc then to be plunged in a bark or hot-bcd, and kept moist.”

2498. T he management o f cuttings, after they are planted, depends on the general

principle, that where life is weak, all excesses of exterior agency must have a tendency

to render it extinct. No cutting requires to be planted deep, though such as arc large

(z) ought to be inserted deeper than such as are small (/, A). In the case of evergreens,

the leaves should be kept from touching the soil (A), otherwise they will damp or rot

off; and in the case of tubular-stalked plants, which are in general not veiy easily

struck, owing to the water lodging in the tube, and rotting the cutting, both ends (/)

may in some cases (as in the common lioncysuckio) be advantageously inserted in the soil,

as, besides a gi-eatcr certainty of success, there is a chance that two plants may be produced.

Too much light, air, water, heat, or cold, arc alike injurious. • To guard against

tliese extremes in tender sorts, the best means hitherto devised, is that of enclosing an

atmosphere over the cuttings, by means of a hand or bell glass, according to their

delicacy. This preserves an uniform stillness and moisture of atmosphere. Immersing

the pot in earth (if tlie cuttings arc in pots) has a tendency to preserve a steady unifonn

degree of moisture at the roots ; and shading, or planting the cuttings, if in the open air,

in a shady situation, prevents the bad effects of excess of light. The only method of

regulating the heat is by double or single coverings of glass or mats, or botli. A handglass

placed over a bell-glass will preserve, in a shady situation, a very constant degree

of heat. What the degree of heat ought to be, is generally decided by the degree of

heat requisite for the mother plant. Whatth-er dcgi'cc of heat is natural to the mother

plaiit when in a growing state, will, in general, be most favourable to the growth of the

cuttings. There arc, however, soine variations, amounting nearly, but not (¡uite, to

exceptions. Most species of tlic ¿rica, Daliha, and Pelargonium strike better when

supplied ivitli rather more heat than is requisite for the growth of these plants in greenhouses.

TIic myrtle tribe and camellias require rather less ; and in general it may be

observed, that to give a less portion of heat, and of every thing else projicr for plants

in their rooted and growing state, is the safest conduct in respect to cuttings of ligneous

plants. Cuttings of deciduous hardy trees taken off in autumn, should not, of course,

be put into heat till spring, but should be kept dormant, like the motlicr tree. Cuttings

of succulents, like geraniums, will do well both with ordinary and cxtraordinaiy heat.

2499. P ip in g is a mode o f prop ag ation by cuttings, and is adopted with herbaceous plants

having jointed tubular stems, as tbe Dianthus tribe ; and several of the grasses, and tree

arundos, might be propagated in this manner. When the shoot has nearly done growing,

which generally happens after the blossom has expanded, its extremity is to be sepai-ated

at a part of the stem where it is nearly, or at least somewhat, indurated or ripened. Tins

separation is effected by holding the root end between the finger and tlinmb of one band,

below a pair of leaves, and with the other, pulling the top part above the pair of leaves,

so as to separate it from the root part of the stem at the socket formed by the axillie oi

the leaves, leaving the stem to remain with a tubular or pipe-looking termination. _ These

pipings, or separated parts (A), arc inserted iritliout any further preparation in finely

sifted earth, to the depth of the first joint or pipe, gently firmed, with a small dibber ;

tlicy are then watered, a hand-glass placed over them, and their future management

regulated on the same general principles as that of cuttings. _ _

2500. Prop ag atio n by leaves. “ This mode of propagation is of considerable antiquity,

though till lately it has not been much practised. It is said by Agricola (V A g ric u lte u r

F a r fa it, frc., cd. 1732.) to be the mvention of Frederick, a celebrated_ gardener at

Augsburg, and to have been first described by Mirandola, in \\\s M a n u a le d i G ia rd in ie n ,

published in 1652. Subsequent experiments by C. Bonnet, of Geneva ; Noisette, Ihoum,

Neumann, and Pepin, of Paris ; Knight, Herbei-t, and others, in England ; and quite

recently by Lucas, in Germany, have proved that there is no class of plants winch inaj

not bo propagated by leaves. It has been tried with success with cryptogamous plants,

with endogens and exogens, with the popular divisions of ligneous and herbaceous

plants, annuals, biennials, and perennials, and with the leaves of bulbous plants and

palms.” (Loud on's H o rtic u ltu ris t, p. 266.) ^ i ___.i,.

2501. “ T h e conditions generaUy required f o r rooting leaves arc, that the Icat be ncaily

full grown ; that it be taken off with the petiole entire ; that the petiole be inserted irom

au eighth to half an inch, according to its length, thickness, and texture, in sandy loam,

or ill pure sand on a stratum of rich soil ; and that both the soil and the atmosphere be

kept uniformly moist, and at a liighcr temperature than is required for ^oted plants ot

the same species. The leaves of such succulents as Cacalia, Crassula, Cotyledon, Aa-

lanchoe, PortuUica, S ò d um , 5cmpervìvum, Cactus, and similar plants, root when laid

on the surface of soil, with the upper side to the light, and the soil and atmosphcie

arc kept sufficiently close, moist, and warm. The first change that takes place ts_the

foi-mation of a callosity at the base of the petiole ; after which, at the end or a peiiod,

which varies greatly in different plants, roots are produced, and eventually, at an equally

varying period, a bud from which a leafy axis is developed. M._ Pepm states that i'°ofed

leaves of Iloya carnosa, and those of several kinds of A'loc, did not produce a bud till

after the lapse of ten or twelve yeaa-s. The leaves before they emit roots be

slightly shaded to prevent excessive perspiration during sunshine, but attcrivards they

may be fully exposed to the light.” (/AAA p. 267.) i i ♦

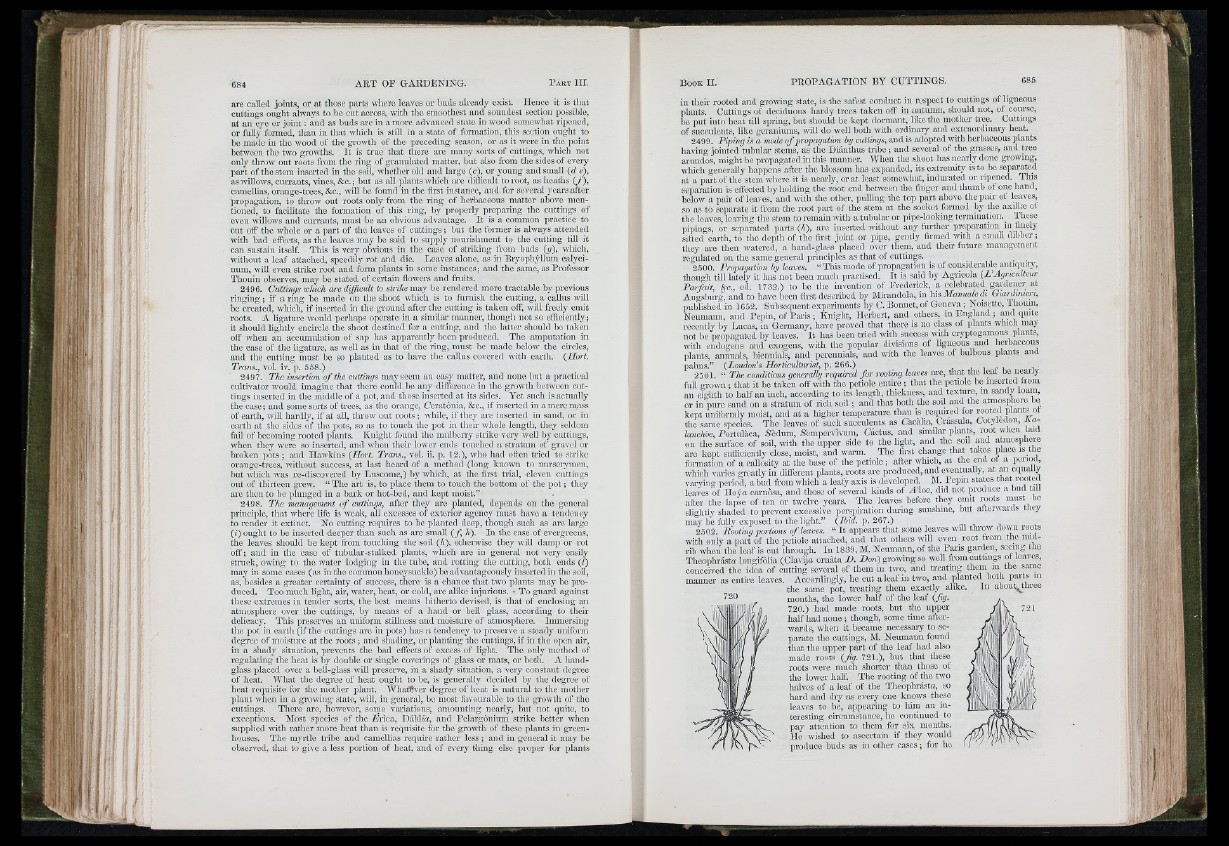

2502. H ooting p ortions o f leaves. “ It appears that some leaves will throw down lOots

with only a part of the petiole attached, and that others will even root from the midrib

when the leaf is cut through. Iu 1839, M. Neumann, of the Pans garden, seeing tlic

Theophrasta longifolia (Clavija ornata D . D o n ) growing so well from cuttings ot leaves,

conceived the idea of cutting several of them in two, and treating them in the same

manner as entire leaves. Accordingly, he cut a leaf in two, and planted both parts m

the same pot, treating them exactly alike. In aboul;^tlirce

months, the lower half of the leaf (fig .

720.) had made roots, but the upper

half had none ; though, some time afterwards,

when it became neccssai-y to separate

the cuttings, M. Neumann found

that tlic upper part of the leaf had also

made roots ( fig . 721.), but that these

roots were much shorter than those of

the lower half. The rooting of the two

halves of a leaf of the Theoplirast/i, so

hard and dry as every one knows these

leaves to be, appearing to liim an interesting

ch-cuinstaiicc, he continued to

pay attention to them for six months.

He wished to ascertain if they would

produce buds as in other cases ; for he