!|l'

a tree of this description happens to die, it is cut out, and the position of those adjoining is altered so as

to supply its place.

4413. The s um m e r m a n a g em en t o f M r . S e ym o u r 's tre e s is thus given by his so n :—“ In the spring, as

soon as the young shoots have grown to about 1 in. long, we begin to disbud or thumb-prune them by

taking off all the young shoots where there is no blossom or fruit, except the lowest one upon the bearing

branch, and th at at the extreme point of it: this end shoot is allowed to growabout 3iu., and is then

stopped; and the buds by the fruit ali broken off to about four of their bottom leaves, so as to make a

cover for the young fruit until the time of thinning, when those little spurs are taken away with the fruit

that is not wanted, and the others are retained along with the fruit that is left. By so doing, we are only

growing th e shoot that we shall want next year for bearing fruit, which gives our trees an opportunity

of extending themselves, and making good wood. Instead of taking off the summer laterals or water

shoots (as they are sometimes called), as is generally done, we lay them in at regular distances, the same

as we should a natunil spring sh o o t; and, if they do not bear fruit the next summer, they will produce

line bearing wood for a future y e a r; so that we have not to shorten those strong shoots, but lay them in

their whole length for secondary leading branches, as we have a t this time shoots laid in above lift, long,

of last year’s growth, with fruit upon th eir laterals. When the young shoots at the base of the fruit-

bearing ones, or th e extending part of the leading branches, have grown 4 in. or 5 in., they are tied down

to the other branches as close as they will admit without breaking or pinching them, and kept close to

the wall through the summer. There will be found, when disbudding, a t the base of the shoots, small

buds that are not likely to make a shoot that season ; but they must be retained, as they will produce a

shoot in a future year, and then bring the young wood nearer home.” (G a rd . M a g ., vol. vi. p. 4.36.)

The merit of Sejnnour’s method consists in the great regularity of the principal branches, and in per-

initting brunches,winter <

which experience proves requisite. On referring to the figure it will be observed that the lower branches

proceed almost in a direct line from th e upright portion of the stem, and nearly a t right angles. But the

'lg only bearing and succession shoots to grow between th e principal brunches.

There, after the

r pruning, no tw'o-year-old shoots are left. It is, however, necessary to point out a modification

.vill not freely diverge to this extent, at a tangent to its upright course; and the consequence i; ,

these branches become weak, and are apt to perish. The branches should therefore be allowed to take

th eir natural divergence, about 45°, in the lirst instance, and then gradually bring them to th e required

^°4414*.” sfe«//e, gardener at Vaux Praslin, adopts a mode of training and pruning, which, however, is

applicable only to very young .rt peach . trees,. in thcir first and second a years.year

In the first year ho does not

.......................‘ n t h e t w .....................................................................................................

at all cut or sliorten tiie’ two original or prmcipal branches, called the m è r e branches. T h e young tree

has only to be fixed to the wall or trellis, requiring no other treatment till the fall of the leaf. By

leaving these m è r e branches a t full length, and only disbudding late in the autumn, the vigour of the

young tree is greatly promoted, lie trains these principal branches to a much wider angle than the

Montreuil gardeners, perhaps 60° or 65°, instead of 45°. At the approach of w inter he practises l'éb o u r -

g eonn emen t à sec ,\eay \ng only four buds on each branch, and removing the rest neatly with a sharp

knife. At Montreuil the m e r e branches are cut in or shortened In the first year, and disbudding i.s

delayed till the leaves be developed in the following year. By disbudding a t this season, the young tree

not only suffers an unnecessary check or injury, b u t the consequence is, th a t th e buds left, instead of

forming good shoots, develope themselves into numerous brindille s. l.ate in the autumn of the second

year Hiculle cuts in, to th e extent of one third, the four lateral branches produced on each of his mèi-e

hranclics. In the foUowing year, he disbuds th e lateral branches to the extent of one half ; and in the

--------- - —aotioe long ago

future management he practises winter disbudding greatly in place of p ru n in g ; a practice ago

strongly recommended by Nicol in his horticultural writings. By S

Sieulle’s method, Du I P etit Thouars

Thouars

remarks, the young - tree ‘-- --is i------------- more quickly l-Ul..-I.------ brought U» »to rt cn fill iits »rt place on on the espalier = ; it is afterwards much

.uv.

A.W.U ......... - » . - - - ® allowed to unfold themselves ; tiie r

cessity of thinning the fruit is thus in a great measure superseded, and the peaches produced are larger

and-finer. (H o r t. T o u r , p. 479.)

4415. T h in n in g the f r u i t . According to th e ordinary practice; the blossoms often set more fruit than

the trees can support, or than have room to attain full growth ; and if all were to remain, it would h urt

the trees in their future bearing: therefore they shouldbe timely thinned, when of the size of large peas or

half-grown gooseberries. There should be a preparatory thinning before the time of stoning, and a final

thinning afterwards; because most plants, especially such as have overborne themselves, drop many of

their fruit at that crisis. Finish the thinning with great regularity, leaving those retained at proper

distances, three, four, or five, on strong shoots, two or three on middling, and ouc or two on the weaker

slioots ; and never leaving m ore thau one peach a t the same eye. T h e fruit on weakly trees thin more

in proportion. (A b e r c rom b ie .)' ,

4416. lle n o v a tin g old d ecaying tre e s. Head down, and renew th e soil from an old upland pasture;

and, if the bottom of th e border is moist, or if th e roots have gone more than 2 ft. downwards, pave the

bottoni or otherwise render it dry and impervious to roots a t th e depth of 2 ft. from the surface. In

general, however, it will be found preferable to plant new trees, as peach trees, when severely cut, are

ap t to exude gum to an injurious degree.

4417. P ro te c tin s blossoin. This may require to be done by some of th e various modes already enumerated

(2644. to 2656.). Forsyth recommends old netting as the best covering. Jn the garden of the Horticultural

Society woollen netting has been used, and also Scotch gauze and bunting, and both with the

greatest success.

4418. H a r r iso n protects his trees from the frost, in tliemonth of January, by branches of broom: these

are previously steeped in soap-suds, mixed with one third of urine, for forty-eight hours, in order to

clear them from insects, and. when dry, disposed thinly over the whole tree, letting them remain on only

until th e trees begin to break into leaf. At the time of the blooming and setting of the fruit he applies

cold water in the following manne r; viz.: —If, upon visiting th e trees, before the sun is up, in the

morning, after a frosty night, he finds that there is any appearance of frost in th e bloom or young fruit, he

waters the bloom or young fruit thoroughly with cold water, from th e garden-engiue ; and he affirms,

th at even if the blossoms br young fruit are discoloured, this operation recovers them, provided it he

done before the sun comes upon them. He fa rther says, that he has sometimes had occasion to water

particular parts o fth e trees more than once in the same morning, before he could get entirely rid of the

effects o fth e frost. Dr. Noehden remarks (i/o?t. T r a n s .,v o l. ii.) “ th a t this operation of watering before

sunrise, in counteracting the frost, seems to produce its effect in a manner analogous to the application

of cold water to a frozen joint or limb, which is injured by the sudden application of w a rmth.” Harrison

discovered this method by the following accident:—“ In planting some cabbage plants, among the rows

of some kidneybeans, very early in the morning, after a frosty night, in spring, before the sun was high

enou°-h to come upon the frosted beans, he spilt some of th e water upon them which he used in planting

th e cabbage-plants; and, to his surprise, he found that the beans began immediately to recover.” “ Cold

water,” Mr. Thompson observes, “ may be applied with some good effect, when the vegetable tissue is

not too far injured, or ruptured by the fro s t; but it will not prove a remedy for any thing beyond a very

slight affection. It will, however, be of considerable service, not only as a medium by which the thawing

is more gradually accomplished, b u t also in consequence of th e moisture it supplies ; for evaporation

operates in a most powerful degree in clear weather in spring; and at that season, when there is no

ciinopy of clouds, such weather is most likely to occur.”

4419. R ip e n in g peaches o n leajless branches. Whenever the part of the bearing branch, which extends

beyond the fruit, is without foiiagc, the Iruit itself rarely acquires maturity, and never its proper flavour

and excellence. This Knight conjectured to b e owingto the w antof the returning sap which would have

been furnished by the leaves ; and he proved It experimentally, by inarching a small branch immediately

above ih o fruit. The fruft, in consequence, acquired the highest degree of maturity and perfection.

4420. S um m a r y o f cu ltu re . The following is from an admirable paper on the culture of the peach and

nectarine, by Mr. Callow, in the tenth volume of the G a rd en e r's M a g a zin e :—“ Although so much has

been written on the pruning, training, and management of peach trees, all that is necessary to be known

may be reduced to a very few words, and carried into effect by any person who will attend to the follow-

ing sliort directions: — Use a strong loam for the b o rd e r; never crop i t ; add no manure; keep tlie trees

thin of wood by disbudding and the early removal of-useless wood; shorten each shoot according to its

strength at the spring, or rather autumn, p ru n in g ; elevate the ends of the leading branches so that they

may all form the same curvilinear inclination with the hori'zon ; and, what is of the utmost importance

in the culture of the peach, a t all times keep the trees in a clean and healthy state.” Mr. Callow’s mode

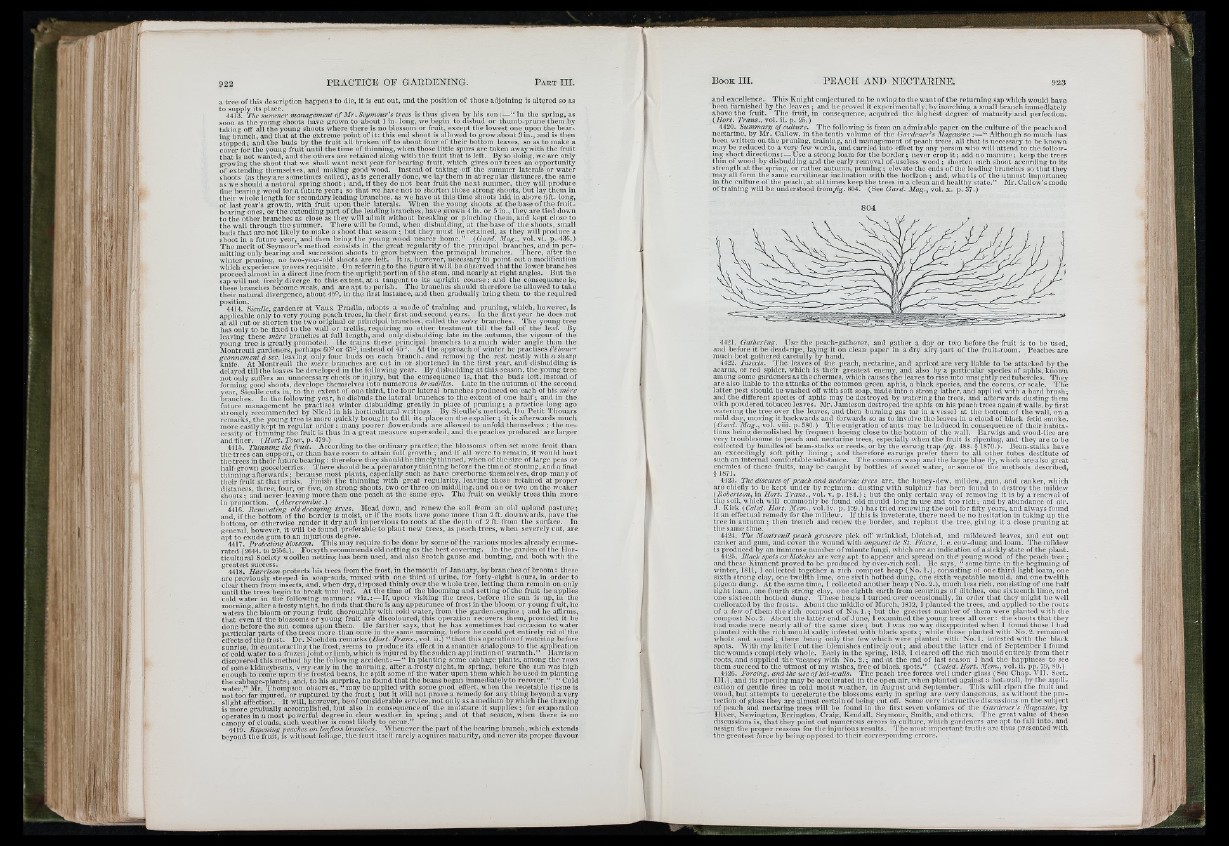

of training will be understood fromjfg. 804. (See Gard. M a g ., vol. x. p. 37.)

4421. G a th e rin g . Use the peach-gatherer, and gather a day or two before the fruit is to be used,

and before it be dead-ripe, laying it on clean paper in a dry airy part of the fruit-room. Peaches are

much best gathered carefully by hand

AAOO Tm.'totote 'I'!,« IrtrtTr4422. In s e c ts . The lea«v»e rst i*o ffl ,t«h er t peach, nectarine, and apricot are very liable to be attacked by the

acarus, or red i spider,.

which is their greatest enemy, and also by a particular species of aphis, known

among some gardeners a; the chermes,, ,, which causes the leaves to rise into unsightly .

red tubercles. They

are also liable to the attacks of the common green aphis, a black species, and the coccus, or scale. Th'e

latter pest should be washed off with soft soap, made into a strong lather, and applied with a hard brush;

and the different species of aphis may be destroyed by watering the trees, and afterwards dusting them

with powdered tobacco leaves. Mr. Jamieson destroyed the aphis on his peach trees against walls, by first

watering the tree over the leaves, and then burning gas ta r in a vessel a t the bottom of the wall, on a

mild day, moving it backwards and forwards so as to involve the leaves in a cloud of black fetid smoke.

(G a rd . M a g ., vol. viii. p. 580.) The emigration of ants may be induced in consequence of their habitations

being demolished by frequent hoeing close to the bottom of the wall. Earwigs and wood-lice are

very troublesome to peach and nectarine trees, especially when the fruit is ripening, and they are to be

collected by bundles of bean-stalks or reeds, or by the earwig trap (Jig. 488. § 1870.). Bean-stalks have

an exceedingly soft pithy lining ; and therefore earwigs prefer them to all other tubes destitute of

such an internal comfortable substance. The common wasp and the large blue fly, which are also great

enemies of these fruits, may be caught by bottles of sweet water, or some of the methods described,

§ 1871.

4423. T k e diseases o f peach a n d n e c ta rin e trees are, the honey-dew, mildew, gum, and canker,-which

are chiefly to be kept under by regimen: dusting with sulphur has been found to destroy the mildew

(R o b e rtso n , in H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. v. p. 184.); but the only certain way of removing it is by a renewal of

the soil, which will commonly be found old mould long in use and too rich; and by abundance of air.

J . Kirk (Caled. I lo r t. M e in., vol.iv. p. 159.) has tried renewing the soil for fifty years, and always found

it an effectual remedy for the mildew. If this is inveterate, there need be no hesitation in taking up the

tree in autumn ; then trench and renew th e border, and replant tlie tree, giving it a close pruning at

the same time.

4424. The M o n tr e u il peach g row e r s pick off wrinkled, blotched, and mildewed leaves, and cut out

canker and gum, and cover the wound with o n g u cn t de S t. Fiaci-e, i.e . cow-dung and loam. The mildew

is produced by an immense number of minute iungi, which are an indication of a sickly state of the plant.

4425. B la c k spots o r blotches are very apt to appear and spread on th g young wood of th e peach tree ;

and these Kinment proved to b, e, p^ roduced b_y over-rich soil. He ssanyi-sc, ““ s?or>mmen tHimrvieo in ttUheo bUeogcirninnniinr.g« o«fr

winter, 1811, I collected together a rich compost heap (No. 1.), consisting of one third light loam, one

sixth strong clay, one twelfth lime, one sixth hotbed dung, one sixth vegetable mould, and one twelfth

pigeon dung. At the same time, I collected another heap (No. 2.), much less rich, consisting of one half

light loam, one fourth strong clay, one eighth earth from scourings of ditches, one sixteenth lime, and

one sixteenth hotbed dung. Tliese heaps I turned over occasionally, in order th a t they might be well

meliorated by th e frosts. About the middle of March, 1812, I planted the trees, and applied to the roots

of a few of them the rich compost of No. 1.; but the greatest number of them were planted with the

compost No. 2. About the latter end of June, I examined the young trees all o v e r: the shoots that they

had made were nearly all of the same size ; but 1 was no way disappointed when I found those I had

planted with the rich mould sadly infested with black spots ; while those planted with No. 2. remained

whole and sound; there being only the few which were planted with N o .l. infested with the black

■;s. With my knife I cut the blemishes entirely o u t; and about the latter end of September I found

wounds completely whole. Early in the spring, 1813, I cleared oft' the rich mould entirely from their

spots.the f ' ’ ’

roots, and supplied ’■ ’ the vacancy with No. 3 2 .; and at f

the end of last season I had the happin

them succeed to the utmost of my wishes, free of black spots.” (Caled. Hort. M em ., vol. ii. pp

4426. F orc ing, a n d the use o f hot-walls. The peach tree forces well under glass (See Cha]

>f bla

peacl

______________________________________ . .lap. VII. Sect.

H I.), and its ripening may be accelerated in the open air, when planted against a hot-wall, by the apjili-

, _ . ; ope____, ............................„ .

pp. 79, SO.)

cation of gentle fires in cold moist weather, in August and September. This will ripen the fruit and

and

wood, but attempts to accelerate the blossoms early in spring are very dangerous, as without the protection

of glass they are almost certain of being cut oft'. Somo very instructive discussions on the subject

of peach and nectarine trees will be found in the first seven volumes of the Gardene r’s Magazine , by

Hiver, Newington, Errington, Craig, Kendall, Seymour, Smith, and others. The great value of these

discussions is, that they point out numerous errors in culture, which gardeners are apt to fall into, and

assign the proper reasons for the injurious results. The most important truths are thus presented with

th e greatest force by being opposed to thoir corresponding errors.