C lIA l\ II.

Structures used in Gardening.

1981. B y garden-siructures wc mean to designate a class of buildings which differ

from all other ai-cWtectural productions, in being applied to the cultm*e, or used exclusively

os the habitations of plants. As edifices, the principles of thcir constmction belong

to arcliitecture; but as habitations for plants, thcir ibrm, dimensions, exposure, ancl,

in many respects, tlio materials of which they arc composed, ai-e, or ought to be, guided

by tho principles of culture, and therefore under the control of the gardener. They

may be arranged into the movable, as the hotbed frame ; fixed, as the wall, trellis, &c. ;

and permanent, as the hothouse.

S e c t . I. Temporary or Movable Structures.

1982. O f these, some are for protecting plants in fixed places, as against walls or

trellises, and exemplified in the different methods of covering by frames of canvas,

netting, or glass ; others constitute habitations for plants, as the hotbed frame, pit, &c.

S u b s ec t . 1. Structures Portable, or entirely Movable.

1983. Portable structures arc the flowcr-stage, canvas or gauze frame or case, glass

frame or case, glass tent, and glazed frame.

1984. O f thefiower-stage there arc two principal species ; the stage for florists’ flowers

and the stage for decoration.

1985. The stage fo r florists' flowers, when portable, is commonly a series of narrow

shelves, rising in gradation one above the other, and supported by a frame and posts, so

as to be 3 or 3 | feet from the ground at the lowest shelfi These shelves avc enclosed,

generally, on tlirec sides by boards or canvas, and on the fourth side by glass doors. Tins

stage, when in use, is placed so that the glazed side may front the morning sun, or the

north, in order that tho colours of auriculas, carnations, &c., may not be impaired by it.

1986. The decorative stage consists of shelves, rising in

gradation, in various forms, according to taste and parti-

culai” situation. Those to be viewed on all sides are commonly

conical {fig. 555.) or pyramidal; those to be seen

only on one side, triangular. One, used by Mi*s. Fox,

widow of the late celebrated Charles James Fox, at St.

Ann’s Hill, Sui'rey, will be found figured and described

in the Gardener’s Magazine, vol. v. p. 274.

1987. The opaque coveringframes arc borders of board

strengthened by cross or diagonal slips of wood or rods of

iron, and covered with canvas, gauze, woollen, or common netting, or oiled paper. They

arc used for protecting plants from cold, or for sheltering from wind, or shading, cither

singly, supported hy props, or connected so as to form roofs, cases, or enclosures.

1988. The transparent covering, or glazed frame or sash, consists of a boundary fi-ame,

composed of two side pieces called styles, and two end pieces called the top and bottom

rails, with the interspace divided by rebated bars to contain the glass. I t is used as the

opaque covering frames, and has the advantage of them in admitting abundance of light.

In general, the rebated bars are inserted in one plane, as in common hotbed sashes ;

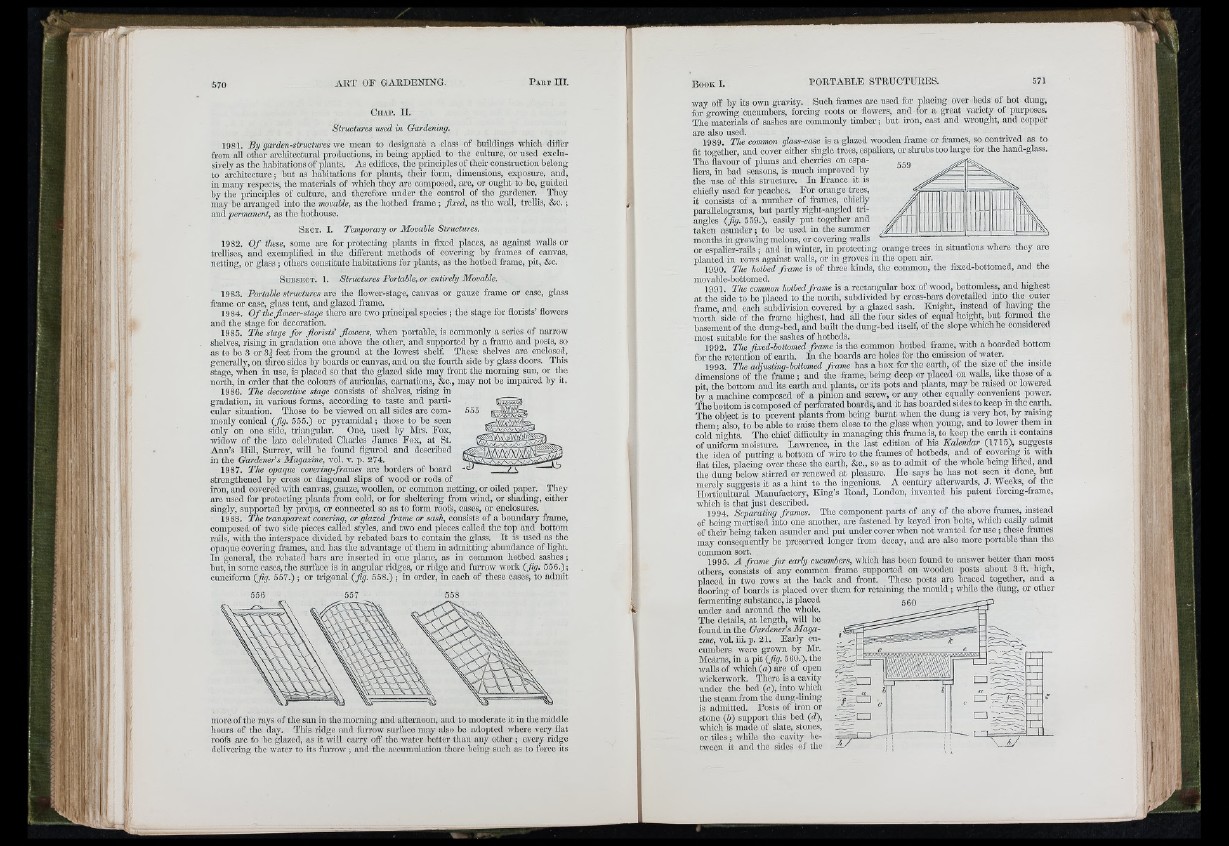

but, in some cases, the surface is in ang-ular ridges, or ridge and fuiTow work (fig. 556.);

cuneiform (fig. 557.) ; or trigonal (fig. 558.) ; in order, in each of these cases, to admit

more ofthe rays of the sun in the morning and afternoon, and to moderate it in the middle

hours of the day. This ridge and furrow surface may also be adopted where very flat

roofs arc fo be glazed, as it will can-y off the water better than any otlier; every ridge

delivering the water to its fun-ow ; and the accumulation there being such as to force it.s

A M

way off by its own gravity. Such frames ai-c used for placing over beds of hot dung,

for growing cucumbers, forcing roots or flowers, and for a great variety of purposes.

The materials of sashes arc commonly timber; but iron, cast and wrought, and copper

arc also used. .

1989. The common glass-case is a glazed wooden frame or frames, so contrived as to

fit together, and cover either single trees, espaliers, or shrabs too large for the hand-glass.

The flavour of plums and chcn-ies on espaliers,

in bad seasons, is much improved by

the use of this structure. In France it is

cliiefly used for peaches. For orange trees,

it consists of a number of frames, cliiefly

parallelogi-ams, but partly right-angled triangles

(fig. 559.), easily put together and

tiikcn asunder; to be used in the summer

months in growing melons, or covering walls

or cspalier-rails; and in winter, in protecting orange trees in situations where they are

planted in rows against walls, or iu groves in the open air.

1990. The hotbed frame is of tlirec kinds, the conunon, the fixcd-bottomcd, and the

movable-bottomed. . , . ,

1991. The common hotbed frame is a rectangular box of wood, bottomless, and highest

at the side to be placed to the north, subdivided by cross-bars dovetailed into the outer

frame, and each subdivision covered by a glazed sash. Knight, instead of having the

iiorth side of the frame highest, had all the four sides of equal height, but formed the

basement of the dung-bed, and built the dung-bed itself, of the slope which he considered

most suitable for the sashes of hotbeds.

1992. The fixed-bottomed frame is the common hotbed frame, with a boarded bottom

for the retention of earth. In the boai-ds are holes for the emission of water.

1993. The adjusiing-bottamed frame has a box for the earth, of the size of the inside

dimensions of the fram e; and the frame, being deep or placed on walls, like those of a

pit, the bottom aud its earth and plants, or its pots and plants, may be raised or lowered

by a machine composed of a pinion and screw, or any other equally convenient power.

The bottom is composed of perforated boards, and it has boarded sides to keep in the earth.

The object is to prevent plants from being bm-nt when the dung is vei-y hot, by raising

them; also, to be able to raise them close to the glass when young, and to lower them^in

cold nights. The cliief difiiculty in managing this frame is, to keep the earth it contains

of uniform moisture. Lawrence, in the last edition of his Kalendar (1715), suggests

the idea of putting a bottom of wire to the frames of hotbeds, and of covering it with

flat tiles, placing over these the earth, &c., so as to admit of the whole being lifted, and

the dung below stfrred or renewed at pleasure. He says ho has not seen it done, but

merely suggests it as a hint to the ingenious. A century aftci-wards, J . Weeks, of the

Horticultural Manufactory, King’s Road, London, invented his patent forcing-frame,

which is that just described. , ^ ,

1994. Separating frames. The component parts of any of the above frames, mstcad

of being mortised into one another, ai-e fastened by keyed iron bolts, which easily admit

of thcir being taken asunder and put under cover when not wanted for u se; these frames

may consequently be preserved longer from decay, and arc also more portable than tho

common sort.

1995. A frame fo r early cucumbers, which has been found to answer better than rnost

others, consists of any common frame supported on wooden posts about 3 ft. high,

placed in two rows at the back and front. These posts are braced together, and a

flooring of boards is placed over them for retaining the mould ; while the dung, or other

fermenting substance, is placed

under and around the whole.

The details, at length, will be

found in the Gardener’s M agazine,

vol. iii. p. 21. Eai-ly cucumbers

were grown by Mr.

Meai-ns, in a pit (fig. 560.), tho

•walls of wliich (a) arc of open

wickerwork. There is a cavity

under the bed (c), into wliich

the steam from the dung-lining

is admitted. Posts of iron or

stone (b) support tliis bed (d),

which is made of slate, stones,

or tile s ; while the cavity between

it and the sides of the

^