j

il i

i'

I

i

Z i / l

: s. ri;;!,!. I ' ii

r é

h I '

Y % .

leaves abovethat to remain untouched : then cut right across, under an e y e ; and make a small incision in

an angular direction on the bottom of the cutting. When the cuttings are thus prepared, take a pot.

and fill it with sand ; size the cuttings, so that the short ones may be altogether, and those th a t are

tailor in a different pot. Then, with a small dibble, plant them about .5 m . deep in the sand, and give

them a good watering over head, to settle tho sand about them. Let them stand a day or two m a shady

place and if a frame be ready with bottom heat, jilunge the pots to the brim. Shade them well with a

double mat, which may remain till they have struck ro o t; when rooted, take the sand and cuttings out

of the pot. and plant them in single pots, in the proper compost (see § 48.57.). Plunge the pots with the

voung plants again into a frame, and shade them for four or five weeks, or till they are taken with the

...I— .X— l.rt ----->....11., n.-nncnA f/. «-ua li.ri,» various experiments,pots • when they may be gradually exposed to the light. Prom various experiments, II ffoouunndd tthhaatt

pieces of two-year-old wood struck quite w e ll; and in place, therefore, of putting in cuttings 6 in . or

8 in. long 1 have taken off cuttings from 10 in. to 2 ft. long, and struck them with equal success.

Although I at first began to put in cuttings only in the month of August, I now put them m at any

time o fth e year, except when the plants are making young wood. By giving them a gentle bottom heat,

and covering them with a hand-glass, they will generally strike roots in seven weeks or two months.

The citron is most easily struck, and is the freest grower. 1 therefore frequently strike pieces 18 in.

long : and as soon as they are put into single pots, ami taken with the pots, they are grafted with other

sorts, which grow freely. I am not particular as to the time either of striking cuttings or of grafting.’

(Uric<f. .«hri. Mew., vol. iii. p. 308.)

48.50. Jii/ la y e rs. This mode is occasionally practised both on the Continent and m England. At

Monza, near Milan, there was in 1819 a very fine collection of lemon trees in boxes, trained as espaliers,

which were so raised. Tho trees were ñ ft. high, and each box had a portion of trellis attached to it of

that height, and 10 ft. or 12 ft. long, which was wholly covered with branches. Where laying is adopted,

the plants may either be laid down on thcir sides, and laid as stools, or pots may be raised and supported

under the branches to be propagated from. These branches, or their shoots of one or two years growth,

may then be cut or ringed, and bent into the pot, or down through the hole m the bottom, and treated

iu the usual manner, taking care to supply water with th e greatest regularity. Shoots layered in March

will bo fit to separate from the stools as mother-plants in the September following. In general, it may

be observed, that the citron tribe, like other fruit-bearing plants raised from cuttings or layers, though

they may prove very prolific trees, yet seldom grow with such vigour, or produce such large frmt, as

those propagated by budding or grafting on seedling stocks.

48.51. SoU. At Genoa and Florence they are grown in a strong yellow clay, which is richly manured;

ancl this soil is considered, by the first Italian gardeners, as best suited to thoir natures. At Home and

Milan the natural soil is lighte r; but a strong soil is adopted generally for all th e a g rum i,a n a particularly

in the garden of his Holiness the Pope. At Naples, where the trees are ahvays planted in the open ground,

the soil is lighter, and of volcanic origin. A strong soil, in imitation of that of Nervi, is recommended

and adopted by the Dutch. (See F a n Osten, N ied . Hesperides, &c.)

48.52. The French g a rd en e r s , according to Bosc (in N . Cours d 'A g r ., in loco), in preparing a cornpost for

the orange tree, encTeavour to compensate for quantity by quality; because the pots or boxes in which

the plants are placed ought always to be as small as possible, relatively to the size of the tree. 1 he following

is the composition recommended t—-To a fresh loam which contains a third of clay, a third of sand,

a n d a th ird of vegetable matter, and which has lain a long time in a heap, add an equal bulk of half rotten

cow-dung. The following year tu rn it over twice. The succeeding year mix it with nearly one half its

bulk of decomposed horse-dung. Tu rn it over twice or three times, and the winter before using add

a twelfth part of sheep-dung, a twentieth of pigeon-dung, and a twentieth of dried ordure.

4853. M ille r says. “ the best compost for orange trees is two thirds of fresh earth from a good pasture,

and one third part of neat’s dung, 'i'hese should be mixed together a t least twelve months before using,

turning it over every month, to mix it well and to rot the sward. Pass it through a rough screen before

^48;f4. M 'P h a il a n d Abercrombie recommend “ three eighth parts of cow-dung, which has been kept

throe r four

r y ea rs; a fourth part of vegetable mould from tree-leaves; one sixth part of fine rich loam;

and one twelfth ,fth p part

a rt of ro a d -g rit; to this may be added one eighth part of sheep-dung.” {G .R em ., p. 242.

P r . Gard-, p. 574.)

^ 'A%bb.'Mean has tried the following mixture (7/ori. T ra n s ., vol. ii. p. 295.), with which he has “ every

reason to be satisfied. Well prepared rotten leaves, two or three years old, one h a l l ; rotten cow-dung,

two, three, and four years old, one fourth ; and mellow loam one fo u r th ; a small quantity of sand or

road-grit may be added to this compost, which ought not to be sifted too fine.”

48.56. A y re s, who grows excellent table fruit of the citrus, at Shipley, uses ten parts of strong turf-loam,

seven of pigeon-dung, seven of garbage from thedog-kennel or butcher’s yard, seven of sheep-dung, seven

of good rotten horse-dung, and ten of old vegetable mould, mixed and prepared a twelvemonth before

■using. {H o r t. T ra n s ., vol. iv. p. 310.) , , - .

4857. Hende rson, of Wood Hall, a most successful cultivator of tlfe genus Citrus, gives the loHowmg

directions as to so il; “ Take one p a rt of light brown movfld from a piece of ground that has not been

■ ~ • -- -- - -- =- — •--- growing h e a th s; two

cropped or manured for many years ; one part of peat earth, such as j used for

parts of river-sand, or pit-sand, if it be free from mineral substances ; and one part ol

)f rotted hotbed dung ;

with one part of rotted leaves of trees. Mix them all well together, s as to form a compost soil of

uniform quality.” {Caled. H o r t. M em ., \ o \ . n \ . p. 302.)

4858. T em p e ra tu r e . T h e standard temperature for the citrus tribe is 48°; bnt m the growmg season

they require a t least ten degrees of additional heat to force them to produce luxuriant shoots. The air of

th e house in which the plants are kept, whether in boxes or iu the ground, should never bo allowed to fall

under 40°; for though the orange, like the pine-apple, will endure a severe degree of cold for a few hours

without injury, yet, as Mean has observed, if the leaves are once injured, the trees will require three years

to recover their appearance. Ayres never suffers his orangery to be heated above 50° by fire-heat, until

the end of F eb ru a ry ; when the trees show blossom, it is increased to 55°, but never allowed to exceed 60°

by sun-heat, the excess of which he checks by the admission of air till the early part of June, when he

“ begins to force the trees, by keeping the heat in th e house up as near as possible to 75°. F or I do not

consider,” he adds, “ that either citrons, oranges, lemons, or limes, can be grown fine and good with less

hea t.” {H o r t. T ra n s ., vol. iv. p. 811.) The orange, Humboldt observes {De Dislrib . P la n t., p. 158.),

which requires an average temperature of 64°, will bear a very great degree of cold if continued only for

a short time. This is proved by an observation of Dr. Sickler, who says, “ it is remarkable how much

cold and snow the common lemons and oranges will bear at Rome, provided they are planted in a sheltered

situation, not much exposed to the sun. Thus I saw in the two winters of_180-5 and 1806, under

my windows, on Monte Pincio, th ree standard orange trees in the open ground, heavily covered with snow

for more than a week. The green leaves, b u t still more the golden fruits, nearly ripe, looked singular

bu t beautiful amidst the snow; neither fruits nor trees had suffered, being in a sheltered place, while

many branches and leaves of other trees of this kind, which were exposed to the sun. turned black and

died, rendering the whole tree sickly.” {V o lk . O ra n . G a r t., p. 9.) It appears th a t the snow had been

thawed from off these trees gradually, and more by the temperature of the atmosphere than by the direct

rays of the sun, or a current of heated air. This resulted from th eir sheltered and partially shaded

situ a tio n ; and, as Dr. Noehden has remarked {H o r t. T ra n s ., vol. iii. p. 43.), it proves the tru th of the

observation of Knight, that it is more the sudden transition from cold to heat, and th e contrary, than the

degree of either, which destroys vegetables. Whenever orange trees or any tender exotics havebeen

touched during night by frosty they should either be immediately shaded by mats from th e next day s sun,

or thawed by water a t not more than 32° or 33° of temperature. In the northern regions the same tre a tment

is successfully applied to animals. (Sec H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. iii. p. 42. and p. 144.)

4859. Watci-. Orange trees, like other evergreens which delight in a strong soil, are not naturally fond

of wafor; but in this country those in boxes are often much injured for want of a due supply of this

m ateria l; for the earth becoming indurated, the water wets only the surface, and runs over and escapes

by the sides of the pot or b o x ; so th at while th e mass of earth below is dry, the surface has a sune moist

appearance. Mean says, “ when I think, from the appearance of a plant, th at the water does not freclv

enter by the middle or sides of the box, a sharp iron rod, about 3 ft. long, is made use of to penetrate

to the bottom of the earth, and to form a channel for the water, too little or too much of which is equallv

m junous to orange tree s.” Knight {Hort. T ra n s ., vol. ii. p. 229.) watered an orange tree with very strong

liquid manure, and found it grow with equal comparative vigour to the vine and mulberry Ayres, after

the frmt is set, waters with water, in which, at the rate of three barrows of fresh cow-dung, without litter,

two burrows of tresh sheep’s droppings, and two pecks of quick lime have been added to every hogsiiead •

when used, the water is about th e consistence of cream. { I lo r t. T ra n s ., vol. v. p. 310.) The French

water once after shifting with a very strong lessive; they also mulch with recent cow and horse droppings

renewing these once a month or oftener during summer, that there may be always abundance of soluble

matter lor th e water to convey to the roots of the trees. {No u v ea u Cours, &c. art. Orange .) M'Phail

mentions a case m which very large orange trees in the border of a conservatory looked s ic k ly when on

digging deep into the borders to examine th e cause, he found th e earth quite dry, and by afterwards

continuing to water them regularly he recovered them. (G . R em ., p. 242.)

4860. A i r . During the winter season, Miller observes, orange trees require a large share of air when

the weather is favourable; for nothing is more injurious to these trees than stifling them. Tho preven-

riqn of dump, Mean observes, is as essential to the perfection of the plants as the exclusion of cold.

Where these trees are kept in old-fashioned opaque-roofed greenhouses, these cautions as to air and damp

deserve particular attention. Ayres says, the more air orange trees have during the blossoming season

the more certain will they be of setting the fruit. ’

4861. S itu a tio n r e lativ e to light. T h e citrus tribe, in th e ir wild state, are found growing as low trees

in lofty woods, and on the margins of forests, and necessarily in such situations are a good deal shaded

It is also found, in this country, th a t the leaves are of the deepest green when they are partially shaded

either by the construction of the house, or by being planted on the nortli side of trees of taller growth

than their own.

4862. M a n n e r o f g row in g the trees. All the species may either be grown as dwarfs in moderate-sized

lots or boxes; as standards with stems from 2 ft. to 6 ft. high in large boxes; as standards planted iu

h e naked ground; and either as dwarfs or standards planted and trained against a wall or trellis under

glass. The first two modes are more adapted for ornament than producing crops of large fr u it; for all

th e a r t of the gardener will never make plants grow as vigorously in boxes as in the free ground.

Standards planted in the free ground or floor of the conservatory combine both elegance and utility • as

in a house properly constructed, they will make handsome heads, and produce abundant crops of fru it’

The last mode, or that of planting against walls or trellises, is m uch themost certain way of having large

crops. Every part of the plant above ground can thus be brought near the glass and equally exposed to

the sun s influence- a n--d-- -t-h---a t o--f-- -t-h--e- - -a--i-r- --a--n--d —h ea-t :. t••h••e■y] cVa..n.. buue .m..Uo.r Ue .r eadily Jp/lr u„„nCeUd,, aainlKdI Vc.oUIr 1r eCUcIt.Jl yV tLriaitiilnJUedU.,

watered, and washed; and they occupy less room in proportion to th e produce. T h e trees a t Wood

Hall, m West Lothian, some of those at Shipley, and at some places in Devonshire, are trained in this

way. In a very few favourable situations in the South of England, as at Gerston, Luscombe, Coombe ”R oya’l , andfl WW/o1/olrdlv..iill lfeo , ,ifno Devonshire,. Uth—ey_ a__r_e_ it_ra..i.n__eJd _a_g__aJi_n_srt _w__a1l,l1s in .t ,h e o. pen ga’ rd, en. ’ UU...UU

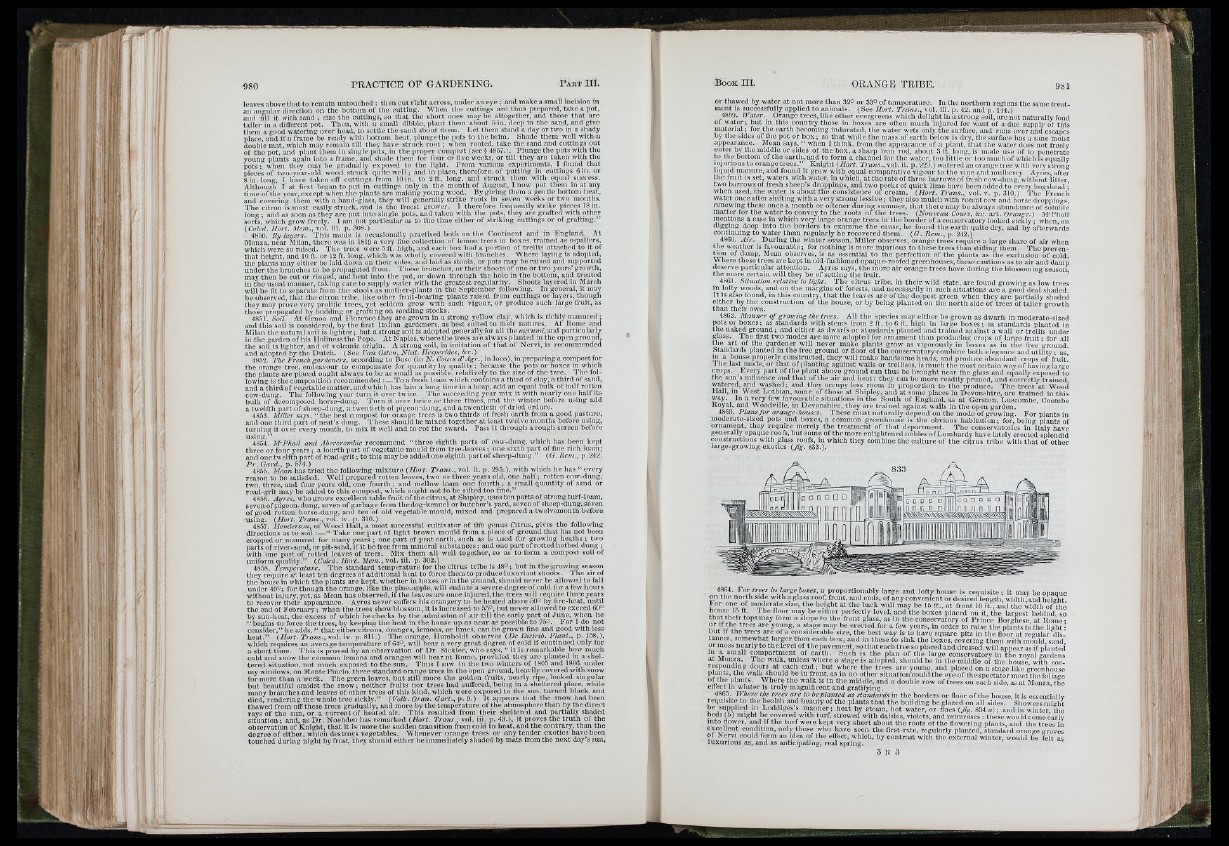

4 ^ 3 . P la n s f o r orange-houscs. These mu.st naturally depend on the mode of growing. For plants in

moderate-sized pots and boxes, a common greenhouse is the obvious h abitation; for, being plants of

ornament, they require merely the treatment of th at department. T h e conservatories in Italy have

generally opaque roots, but some of the more enlightened nobles of Lombardy have lately erected splendid

constructions with glass roofs, in which they combine the culture yf the citrus tribe with th a t of other

large-growing exotics {fig.%ZZ.).

4864. F o r trees in la r g e b o x e s ,a proportionably large and lofty house is req u isite; it mavbeonaQue

a the north side with a glass roof, front, and ends, of any convenient or desired length, width, and height

or one of moderate size, the height at the back wall may be 15 ft., a t front 10 ft., and the widf’ " nouse 15 ft. J he floor may be either perfectly lc

the

'

that their tops may form a slope to th e front glass,

.....rt v „u.. . . . c j .u . „ . a c .u ,,c L.re iiui.L g la s s , HS IJI the conservatory of Prince Borghese, at Rome;

? t V 1? ^ erected for a few years, in order to raise the plants to the lig h t:

b ut if the trees are of a considerable size, th e best way is to have square pits in the floor at regular distances,

somewhat larger than each box, and in these to sink the boxes, covering them with mould sand

qr moss nearly to the level of the pavement, so that each tree so placed and dressed, will appear as if planted

111 a small compartment of earth. Such is th e plan of the large conservatory in the royal gardens

a t Monza. The walk, unless where a stage is adopted, should be in the middle of the house with cor-

responding doors at each en d ; but where the trees are young, and placed on a stage like greenhouse

plants, th e walk should be in front, as m no other situationicould the eye of the spectator meet the foliage

of the plants. Where the walk is m the middle, and a double row of trees on each side, as at Monza the

effect m winter is truly magniflcent and gratifying. ’

4865. Whe re the trees are to be p la n ted a s sta n d a rd s in tlie borders or floor o fth e house, it is essentiallv

requisite to the health and beauty of the plants that the building be glazed on all sides. Showers m ight

¿ supplied m Loddiges’s manner; heat by steam, hot water, or flues (Jig. 834 a ) ; and in winter the

beds (6) might be covered with turf, strewed with daisies, violets, and primroses : these would come early

into ffiiwer, and if the tu rf were kept very short about the roots of the flowering plants, and the trees in

excellent condition, only those who have seen th e first-rate, regularly planted, standard orange groves

qf Nervi could torm an idea ol the effect, which, by contrast with the external winter, would be felt as

luxurious as, and as anticipating, real spring.