.'if , IM lili; ! ;

' f e f l r é i n

‘ i . ' f e á , I, - j ñ

r

iß ; • £ '

ing on tiic smell of the buds and leaves, ra the r than of the flower, would have its effect the greater part

o fth e year, especially after showers.

5098. System atic o r methodical p la n tin g in shrubberies consists, as in flower-planting,

in adopting the Linnæan or natural arrangement as a foundation, and combining at

the same time a due attention to gradation of heights. This mode, executed on a grand

scale, would unquestionably be the most interesting of all, even to general observers ;

but on a small scale it could not be so universally pleasing as the mingled manner, or

the mode by select grouping. The uninsti*ucted mind might be surprised and puzzled

by such an assemblage ; but not perceiving the relations which constitute its excellence,

they would be less pleased than by a profusion of ordinary beauties—by a gi'eat show

of gay flowers and foliage. Dr. Darwin is said to have blended picturesque beauty with

scientific arrangement in a dingle at Lichfield, where he disposed of a large collection of

trees and plants in the Linnæan manner. The same end may be attained on any

description of surface, and with any form of ground-plan, provided turf be introduced,

aud care be taken to elongate the groups containing trees in such a way as to preserve

a sufficient degree of woodiness throughout, both for shelter, shade, and pictiu-csque

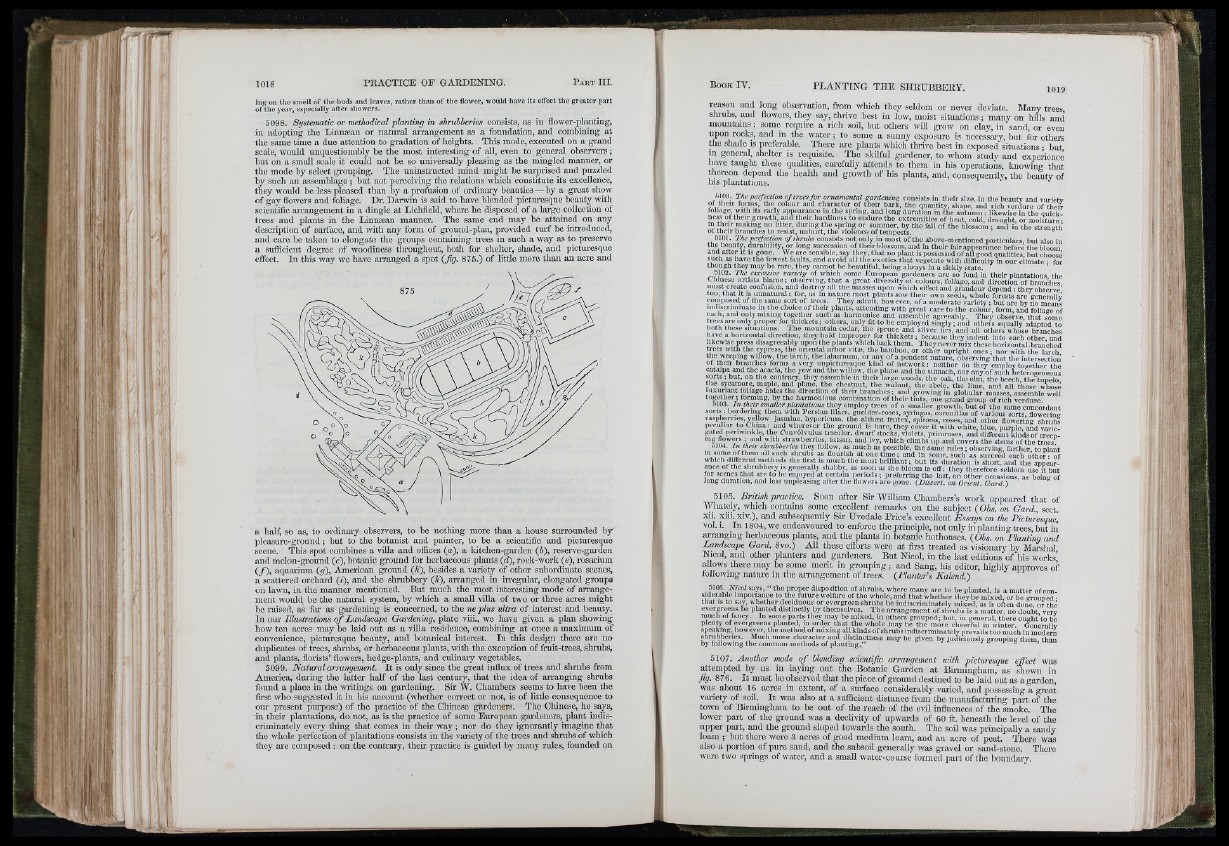

effect. In this way we have arranged a spot (fig . 875.) of little more than an acre and

a half, so as, to ordinary observers, to be nothing more than a house surrounded by

pleasure-ground; but to the botanist and painter, to be a scientific and picturesque

scene. This spot combines a villa and offices (a), a kitehen-garden (b ), reserve-gai’deii

and melon-ground (c), botanic ground for herbaceous plants (5), rock-work (e), rosarium

( /), aquarium (g ), American ground (Ji), besides a variety of other subordinate scenes,

a scattered orcliard (¿), and the shrubbery ( k ), arranged in iiregular, elongated groups

on lawn, in the manner mentioned. But much the most interesting mode of aiTange-

meiit would be the natural system, by which a small villa of two or three acres might

be raised, as far as gardening is concerned, to the ne p lu s u ltra of interest and beauty.

In our Illu s tra tio n s o f Landscape G ardening, plate viii., we have given a plan showing

how ten acres may be laid out as a villa residence, combining at once a maximum of

convenience, picturesque beauty, and botanical interest. In this design there arc na

duplicates of trees, shrubs, or herbaceous plants, with the exception of fruit-trees, shrubs,

and plants, florists’ flowers, hedge-plants, and culinaiy vegetables.

5099. N a tu ra l arrangement. It is only since the great influx of trees and shrubs from

America, during the latter half of the last century, that the idea of arranging shrubs

found a place in the writings on gardening. Sir W. Chambers seems to have been the

first who suggested it in his account (whether correct or not, is of little consequence to

our present piu'pose) of the practice of the Chinese gardeners. The Chinese, he says,

in their plantations, do not, as is the practice of some European gardeners, plant indiscriminately

every thing that comes in thcir way; nor do they ignorantly imagine that

the whole perfection of plantations consists in the vai'iety of the trees and shrubs of which

they ai'C composed : on the contrai’y, thcii' practice is guided by many rules, founded on

r^son and long observation, from which they seldom or never deviate. Many trees

sln-ubs, and flowers, they say, thrive best in low, moist situations; many on hills and

mountains: some require a rich soil, but others will grow on clay, in sand, or even

water; to some a sunny exposure is necessary, but ibr others

the shade is preferable. There arc plants which thrive best in exposed situations • but

m general, shelter is requisite. The skilful gardener, to whom study and experience

have taught these qualities, carefully attends to them in his operations, knowing that

thereon depend the health and growth of his plants, and, consequently, the beauty of

his plantations. "

u . . ., OT > V —: . I. ‘---- 0» — -“..o uu. cOTviui* „1 Liic auLumii; imewise iii tne aiiicK.

ness of thwr growth anil their hardiness to endure the extremities of heat, cold, drought, or molSture ■

m their makiii^g no litter during the spring or summer, by the fall ot the blossom; and l i the strength

Of their branches to resist, unhurt, the violence of tempests.

5101. Tiw p e rfe c tion q f s / u b s consists not only in most o fth e above-mentioned particulars, but also in

the beauty, durability, or long succession of their blossom, and in their fair appearance before the bloom

and after it is gone. We are sensible, say they, that no plant is possessed of all good qualities but choose

¿ c h as have the lewest faults, and avoid all tBe exotics th a t vegetate with difficulty in our climate • for

though they may be rare, they cannot be beautiful, being always in a sickly state. ’

5102. The excessive v a r ie ty of which some European gardeners are so fo n d ín their plantations the

Chinese artists b lam e ; observing, that a great diversity of colours, foliage, and direction of branches

must create confusion, and destroy all the masses upon which effect and grandeur depend: they observe

too, th at it IS u n n a tu ra l; for, as m nature most plants sow their own seeds, whole forests are generallv

compo^d of the same ¿ r t of trees. They admit, however, of a moderate v a rie ty ; but are by no means

indiscnmmate m the choice of their plants, attending with great care to the colour, form, and foliacre of

each, and onlymixing together such as harmonise and assemble agreeably. They observe, that some

trees arc only proper for th ick ets; others only fit to be employed singly; and others equally adapted to

¿ t h these situ¿ ions. T h e fo u n ta in cedar, the spruce and silver firs, and all others whose branches

have a horizontal direction, they hold improper for th ick e ts; because they indent into each other and

likewise press disagreeably upon the plants which back them. They never mix these horizontal-bran’ched

trees with the cypress, th e onenta l arbor vjtge, the bamboo, or other upright ones ; nor with the larch

the weeping willow, the birch, the laburnum, or any of a pendent nature, observing that the intersection

of their branches forms a very u n p ic tu re ¿u e kind of network: neither do they employ together the

catalpa and the acacia the yew and the willow, the plane and the sumach, nor any of such heterogeneous

sorts ; but, on the contrary, they assemble in their larg e woods, th e oak, th e elm, the beech the tuoelo

the sycamore, maple, and plane, the chestnut, the walnut, the abcle, th e lime, and all those w h o se

luxuriant foliage hides the direction of their branches; and growing in globular masses, assemble well

to g e th e r; forming, by the harmonious combination of their tints, one grand group of rich verdure

.)103. I n th e n - s t a l e r p / n t a t i o m they employ trees of a smaller growth, but of the same concordant

so rts ; bordering them with Persian lilacs, guelder-roses, syringas, coronillas of various sorts, flowering

ra sp ¿ rr ie s , yellow jasmine, hypericum, th e althjea frutex, spirieas, roses, and other flowering shrubs

peculiar fo C h in a : and wherever the ground is bare, they cover it with white, blue, purple and vane

gated periwinkle, the Convolvulus tricolor, dwarf stocks, violets, primroses, and different kinds of creep-

with strawberries, tutsan, and ivy, which climbs up and covers the stems o fth e trees.

5104. I n th e ir shrubberies they follow, as much as possible, the same ru le s ; observing, farther, fo plant

'111 such shrubs as flourish a t one time ; and in some, such as succeed each o th er- of

which ¿ fferent methods the first is much the most b rillian t; but its duration is short, and the appear-

anc e of the shrubbery is generally shabby, as soon as the bloom is off: they therefore seldom use it but

for scenes that are to be enjoyed a t certain periods ; preferring the last, on other occasions, as being of

long duration, and less unpleasing after the flowers are gone. (D is s e r t, on Orient. G a rd .)

5105. B r itis h practice. Soon after Sir William Chambers’s work appeared that of

Wliatoly, which contains some excellent remarks on tho subject {O b s. on O a rd ., sect

xii. xiii. xiv.), and subsequently Sir Uvedale Price’s exceUent E ssays on the P ic tu n s q J

vol.i. In 1804,we endeavoured to enforce the principle, not only in planting trees, but to

iirranging herbaceous plants, and the plants in botanic hothouses. {O b s. on P la n tin g and

Landscape G a rd . 8vo.) All these efforts were at flrst treated as visionaiy hy Marshal

Ntcol, and other planters and gardeners. But Nicol, in the last editions of his works

allows there may be some merit in grouping ; and Sang, his editor, highly approves of

following natnre in the an-angement of trees. {P la n te r’s K a le n d .)

, 5106. I f iM soys, “ tho proper disposition of shrubs, where many are to be planted, is a matter of considerable

importance to the liiture welfare of the whole, and th at whether they be mixed, or be srouned •

that IS to say, whether deciduous or evergreen shrubs be indiscriminately mixed, as is often done, or th¿

evergreens be planted distinctly by themselves. The arrangement of shrubs is a matter, no doulit verv

much of fancy. In some parts they may be mixed, in others grouped; but, In general, there ought to be

plenty of evergreens planted, in order that tho whole may be the more cheerful in winter. Generally

speaking,^ however, the method ot m ixing all kinds of shrubs indiscriminately prevails too m uch in modern

shrubberies. Much more character and distinctness may be given by judiciously grouping them, than

by following the common methods of p lanting.” J e f s , vuaii

5107. A n o th e r mode o f blending scientific arrangem ent w ith picturesque effect was

attempted by us ta laying out the Botanic Garden at Birmingham, as shotvn in

flg . 876. It must be observed that the piece of ground destined to bo laid out as a garden,

was about 16 acres in extent, of a surface considerably varied, and possessing a great

variety of soil. It was also at a sufflcient distance from the manufacturing part of the

town of Btomingham to be out of the reach of the evil influences of the smoko. The

lower part of the ground was a declivity of upwards of 60 ft. beneath the level of the

upper par-t, and tho ground sloped towards the south. The soil was principally a sandy

loam ; but there were 3 acres of good medium loam, and an aere of peat. There was

also a portion of piu'c sand, and the subsoil generally was gravel or sand-stone. There

were two springs of water, and a small water-course ibrmed part of the boundary.