■ ' - I !

Willis, and about 3 f acres in the slips. Where a farm is cultivated by the proprietor, it

is found a desirable practice to have pai-t of the more common kitchen-crops, as cabbages,

turnips, peas, potatoes, can*ots, &c., groivn in the fields; the flavour of vegetables so

grown being greatly superior to that of those raised in a garden by force of manure.

Where a farm is not kept iu hand, by annually changing the surface of the garden by

trenching, this effect of enriched grounds is considerably lessened.

2763. To assist in determining the extent of a garden, Marshall observes that an acre

with wall trees, hotbeds, pots, &c., ivill furnish employment for one man who, at some

busy times, will need assistance. The size of the garden should, however, be proportioned

to the house, and to the number of inhabitants it does or may contain. This is

naturally dic tated; but yet it is better to have too much ground allotted than too little,

and there is nothing monstrous in a lai-ge garden annexed to a small house. Some

families use few, others many, vegetables; and it makes a ^-eat difference whether the

owner is curious to have a long season of the same production, or is content to have a

supply only at the more common times. But to give some rules for the quantity of

ground to be laid out, a fiunily of four persons (exclusive of servants) should have a rood

of good-working, open ground, and so in proportion. I f possible, let the garden be

rather extensive, according to the family; for then a good portion of it may be allotted

for that agreeable fi.-uit the strawbeny in all its varieties; and the very disagreeable

circumstance of being at any time short of vegetables will be avoided. I t should be

considered also that ai'tichokes, asparagus, aud a long succession of peas and beans,

require a good deal of ground. Hotbeds will also take up much room, if any tiling considerable

be done in the way of raising cucumbers, melons, &c. (Introd. to Gard. p. 25.)

S e c t . IV . Shelter and Shade.

2764. To combine adequate shelter, with a free exposure to the rising and setting sun,

is essentially necessary, and may be reckoned one of the most difficult points in the

formation of a garden.

2765. The kitchen-garden should hesheltered by plantations; but should by no means he

shaded or be crowded by them. I f walled round, it should be open andfyee on all sides,

or at least to the south-east and west, that the walls may he clothed witli fruit-trees on

both sides. (Nicol, Kal, p. 6.)

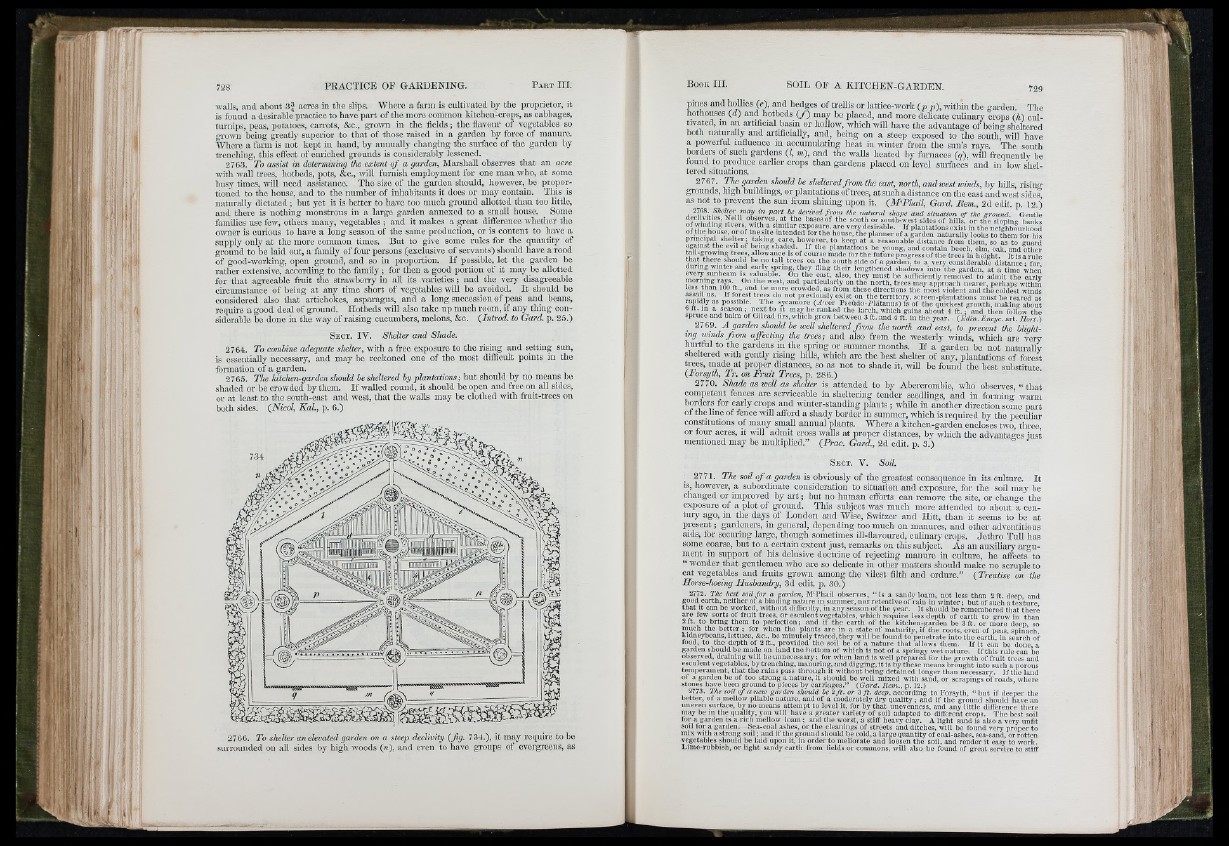

2766. To shelter an elevated garden on a steep declivity (fig. 734.), it may require to be

surrounded on all sides by high woods (n), and even to have groups of evergreens, as

729

pines and hollies (e), and hedges of treUis or lattice-work (p p ), within the garden. The

hothouses (d) and hotbeds ( f ) may be placed, and more delicate culinary crops (h) cultivated,

in an artificial basin or hollow, which wiU have the advantage of being sheltered

both naturally and artificially, and, being on a steep exposed to the south, will have

a poweriM influence in accumulating heat in ivinter from the sun’s rays. The south

borders of such gardens (/, m), and the walls heated by fm-naces (q), will frequently be

found to produce earlier crops than gardens placed on level sm-faces and in low sheltered

situations.

2767. The garden should he sheltered from the east, north, and west winds, by hills, rising

grounds, high buildings, or plantations of trees, at such a distance on the east andwest sides

as not to prevent the sun from shining upon it. (MEhail, Gard. Hem., 2d edit. p. 12.)

Skelter may in p a rt be derived fr om the natural shape and situation o f the ground. Gentle

declivities, Neill observes, at the bases of the south or southwest sides of hills, or the sloffing bankl

ot winding rivers, with _a similar exposure, are very desirable. If plantations exist in the neighbfurhood

of the house, or of th e site intended for the house, th e planner of a garden naturally looks to them for his

prmcipal shelter; taking care, however, to keep a t a reasonable distance from them, so as to guard

against the evil of being shaded. If the plantations be young, and contain beech, elm, oak, and other

of course made for th e future progress of the trees in height. It is a rule

th a t there should be no tall trees on the south side of a garden, to a very considerable distance • for

during winter and early spring, they flmg their lengthened shadows into the garden, a t a time when

IS va uable. On the east, also, they must be sufficiently removed to admit th e early

toss tha^ m i b a"?., n ™ ; particularly on north, trees may approacli nearer, perhaps within

Tf i 1 crowded, as from these directions the most violent ancl the coldest winds

iiv 4 1 previously exist on the territory, screen-plantations must be reared as

rapidly as possible. The sycamore (^i'cer Pseddo-Platanus) is of the quickest growth, making about

L Ih n i f " * a e gains about 4 ft. ; and then follow the

spruce and balm of Gilead firs, which grow between 3 ft. and 4 ft. in the year. (Edin.Encyc. a rt. Hoj-t.)

_ 2769. A garden should be well sheltered from the north and east, to prevent the blighting

winds from affecting the trees; and also from the westerly winds, which are very

hurtful to the gardens in the spring or summer months. I f a garden he not naturally

sheltered with gently rising hiUs, which are the best shelter of any, plantations of forest

trees, made at proper distances, so as not to sliade it, will he found the best substitute

(Forsyth, Tr. on Fruit Trees, p. 286.)

2770. Shade as well as shelter is attended to by Abercrombie, who observes, “ that

competent fences are serviceable in sheltering tender seedlings, and in foi-min" ■warm

bordere for early crops and winter-standing p la n ts ; while in another direction soTne part

of the line of fence will afford a shady border in summer, which is required by the peculiar

constitutions of many small annual plants. Where a kitchen-gai-den encloses two, three

or four acres, it will admit cross walls at proper distances, by wliich the advantao-es iust

mentioned may be multiplied.” (Prac. Gard., 2d edit. p. 3.) ®

S e c t . V. Soil.

2771. The soil o f a garden is obviously of the ^-eatest consequence in its culture. It

is, however, a subordinate consideration to situation and exposure, for the soil may be

changed or improved by a r t ; but no human efforts can remove the site, or change the

exposure of a plot of ground. This subject was much more attended to about a century

ago, in the days of London aud Wise, Switzer and Hitt, than it seems to be at

p resen t; gardeners, in general, depending too much on manures, and other adventitious

aids, for securing large, though sometimes ill-flavoured, culinary crops. Jethi-o Tull has

some coai-se, but to a certain extent just, remai-ks on this subject. As an auxiliai-y argument

ill support of his delusive doctrine of rejecting manui-c in ciiltiu-e, he affects to

“ wonder that gentlemen who are so delicate in other matters should make no scruple to

eat vegetables and ifuits grown among the vilest filth and ordure.” (Treatise on the

Horse-hoeing Husbandry, 3d edit. p. 30.)

‘2772. The best soil fo r a garden, M‘Phail observes, “ is a sandy loam, not less than 2 ft. deep, and

good ea rth, neither ot a binding nature in summer, nor retentive of rain in w in te r; but of such a texture

th a t It can be worked, without difficulty, in any season of the year. It should be remembered that there

are lew sorts of fruit trees, or esculent vegetables, which require less depth of ea rth to grow in than

2 ft. to bring them to perfection; and if the earth of th e kitchen-garden be 3 ft. or more deep so

much th e better ; for when the plants are in a state of maturity, if the roots, even of peas spinach

kidneybeans, lettuce, &c., be minutely traced, they will be found to penetrate into the earth, in search of

food, to th e depth of 2 tt., provided th e soil be of a nature th a t allows them. If it can be done a

garden should be made on land th e bottom of which is not of a springy wet nature. If this rule can be

observed, draining will be unnecessary; for when land is well prepared for the growth of fruit trees and

esculent vegetables, by trenchmg, manuring, and digging, it is by these means brought into such a porous

temperament, th a t the rains pass through it without being detained longer than necessary. If the land

of a garden be of too strong a nature, it should be well mixed with sand, or scrapings of roads where

stones have been ground to pieces by carriages.” (G ard. Rem., p. 12.)

2773. The soil o f a n ew garden should be 2 ft. or 3 f t . deep, according to Forsyth, “ b u t if deeper the

better, of a mellow pliable nature, and of a moderately dry q u a lity ; and if th e ground should have an

uneven surface, by no means attempt to level it, for by th a t unevenness, and any little difference there

may be in the quality, you will have a greater varietv of soil adapted to different crops. The best soil

for a garden is a rich mellow lo am ; and the worst, a stiff heavy clay. A light sand is also a very unfit

soil for a garden. Sea-coal ashes, or the cleanings of streets and ditches, will be found very proper to

mix with a strong soil; and if the ground should be cold, a large quantity of coal-ashes, sea-sand, or rotten

vegetables should be laid upon it, in order to meliorate and loosen the soil, and render it easy to work.

Lime-rubbish, or hght sandy earth from fields or commons, will also be found of great service to stiff

«IP 1

■ft ?