196

description is evidently on the increase in B rita in ; and we should not be surprised, if a t no distant

time they were to combine with them parks, and various other sources of recreation and enjoyment,

now exclusively possessed, a t least in Britain, by the wealthy.

595. Bowling-greens were formerly a depaitmeiit common in the pleasure-grounds of

country seats; bnt they are now seldom to be found there, and are better known as a

description of public gardens in the neighbourhood of towns, for the recreation of the

inhabitants. They generally consist of a square space of half an acre or upwards, well

di'ained, rendered perfectly level, aud sown down with grass seeds, or covered with smooth

turf. The sides ai*e formed of mounds of turf, two or thi’ee feet high, on which is

generally a ten-ace walk, surrounding the bowling-green. The mound is to prevent the

bowls from running off the green, and the walk is for the use of spectators of the game.

These ai-e the essentials, wliich may have various convenient or ornamental accompaniments

; such as a parflion for refreshments, a suiTounding shi-ubbery for walking in, &c.

There is a very handsome one at Bfrmingham, having several acres of pleasure-ground

attached, and with an elegantly fitted up house for the entertainment of the howlers and

their visiters. This house is under the care of the gardener, who has the superintendence

of the grounds, and who supplies the refr-eshments at a price agreed on. There is a

bowling-green at the Ti-indle, near Dudley, with a coffee pavilion and baths attached,

and three ponds for fishing, and taking amusement in boats.

596. Tea gardens ai-e to be found in the neighbourhood of all tow n s; though, till of

late, they have been of so very humble a description as ahnost to escape notice. I t

deserves to he mentioned in this place, that Abercrombie, the author of Every Man his

Own Gardener, published soon after the middle of the last centui-y,— a work which has

had an extraordinary influence in spreading a knowledge of and taste for gardening,—

at one time kept a tea garden between London and Hampstead. I f we ai-e not greatly

mistaken, the time is rapidly approaching, when gardens of this .description will assume

an extent, a splendour, and an interest, of which few at present can form an adequate

idea.

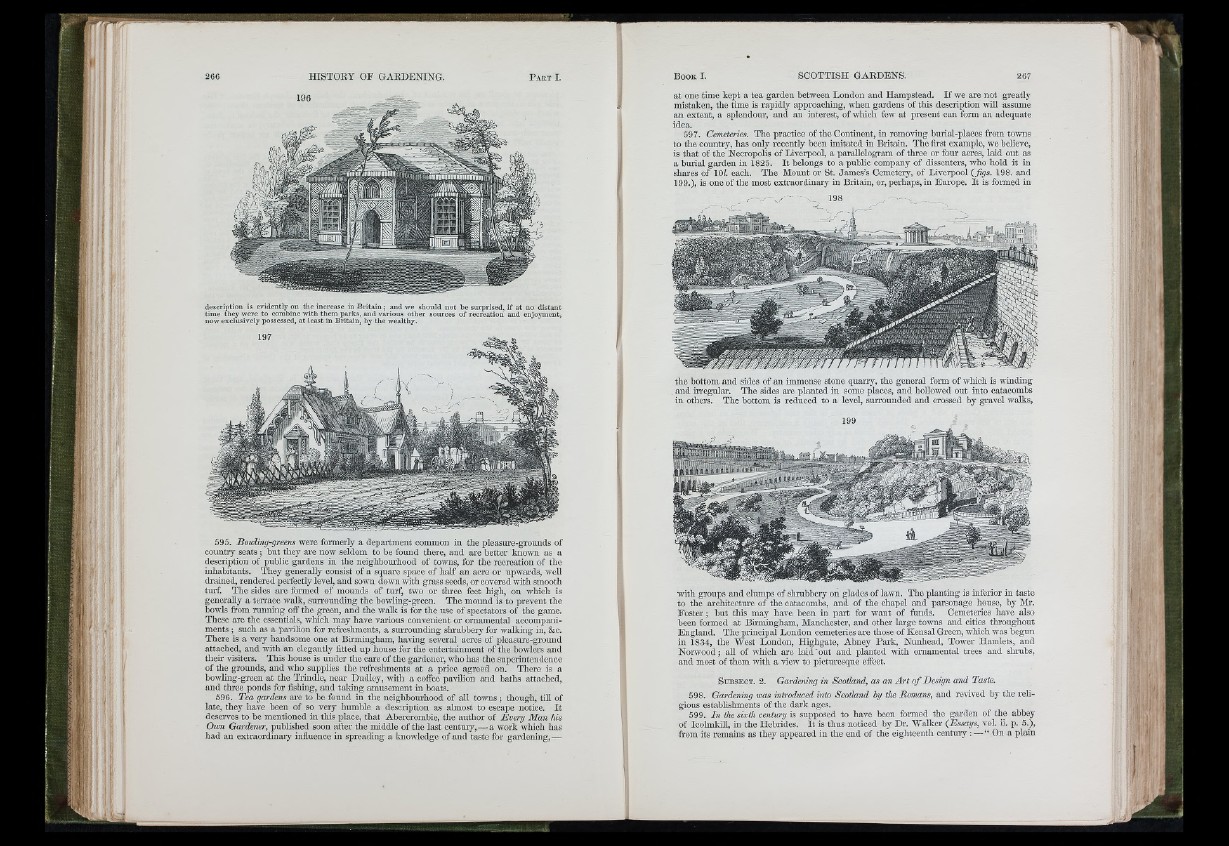

597. Cemeteries. The practice of the Continent, in removing burial-places from towns

to the country, has only recently been imitated in Britain. The first example, we believe,

is that of the Necropolis of Liverpool, a parallelogram of three or four acres, laid out as

a burial garden in 1825. I t belongs to a public company of dissenters, who hold it in

shares of 10/. each. The Mount or St. James’s Cemetery, of Liverpool (figs. 198. and

199.), is oneof the most extraordinary in Britain, or, perhaps, in Europe. I t is foi-med in

the bottom and sides of an immense stone quariy, the general form of which is winding

and irregular. The sides are planted in some places, and hollowed out into catacombs

in others. The bottom is reduced to a level, sun-ounded and crossed by gravel walks,

with groups and clumps of shrubbery on glades of la)vn. The planting is inferior in taste

to tlie architcctm-e of the catacombs, and of the chapel and parsonage house, by Mi-.

F o s te r; but this may have been in part for want of funds. Cemeteries have also

been formed at Bfrmingham, Manchester, and other lai-ge toivns and cities throughout

England. The principal London cemeteries are those of Kcnsal Green, which was begun

in 1834, the West London, Highgate, Abney Park, Nunhead, Tower Hamlets, and

Noi-wood; all of which are la id ‘out and planted with ornamental trees and shrubs,

and most of them with a view to picturesque effect.

S u b s e c t . 2. Gardening in Scotland, as an A r t o f Design and Taste.

598. Gardening was introduced into Scotland by the Romans, and rerived by the religious

establishments of the dark ages.

599. In the sixth century is supposed to have been formed the garden of the abbey

of Icolnikill, in the Hebrides. I t is thus noticed by Dr. Walker (Essays, vol. ii. p. 5.),

from its remains as they appeared in the end of the eighteenth centui-y :— “ On a plain