2120 T lie boilers used to generate steam ave fonned of cast or wronglit iron, or copper,

and are of different shapes. Wronglit iron, or copper, presenting a concave bottom to

tlie fire ai'c generally preferred at present. Mr. Stotliert of Bath, who has had extensive

experience in heating by steam, has given the following as the principles on

which he calculates the size of boilers:— , ^ , r ^ e 1. For forcing-houscs under ordinary circumstances, he finds that 1 square toot oi

bottom surface of boiler is equivalent to 150 squai’C feet of glass.

2. Where bottom heat is required, 1 square foot to 135 feet of glass.

3. For greenhouses, 1 square foot is equal to 200 feet.

For houses that are ill glazed, or placed in an exposed situation, ten or fifteen per cent,

may be added to the proportionate surface of the boiler.

2121. Fu rnaces f o r boilers. “The surface of the fire-grating should be from one-

fourth to one-fifth of the bottom surface of the_ boiler, according to the strength of the

fuel employed.” (H o rt. T ra n s ., 2d scries, vol. i. p. 204.)

2122. T he tubes used f o r convei/ing steam may he formed of the same metals as the

boilers ;* but cast iron is now generally used. Earthen or stoneware tubes have been

tried; but it is extremely difficult to prevent the steam from escaping at their junctions.

The tubes are laid along or around the house or chamber to be heated, much in the

same manner as flues, only less importance is attached to having the first course from the

boiler towards the coldest parts of the house, because the steam-tube is equally heated

throughout all its length. As steam circulates with greater rapidity, and conveys more

heat in proportion to its bulk, than smoke or heated air, steam-pipes arc consequently of

much less capacity than smoke-flues, and generally from 3 to 6 inches iu diameter inside

measure. Where extensive ranges are to be heated by steam, the pipes consist of

two sorts, mains or leaders for supply, and common tubes for consumption or condensation.

Contraiy to what holds in cfrculating water or air, the mains may be of much less

diameter than the consumption pipes, for the motion of the steam is as the pressure; and,

as, the greater the motion, the less the condensation, a pipe of one inch bore makes a

better main than one of any larger dimensions. This is an important point in regard to

appeai-ance as well as economy. In order to procure a large mass of heated nmtter

M‘Phail and others have proposed to place the pipes in flues, where such exist. They

mio-ht also be laid in ccfiular flues built as cellular walls. The most complete mode,

however, is to have parallel ranges of steam-pipes of small diameter, commumcatmg

laterally by cocks. Then, when least heat is wanted, let the steam circulate through one

range of pipes only ; when more, open the cocks which communicate with the second

range ; and when most, let all the ranges he filled with steam.

2123. A s a n example o f a complete and extensive ap p lication o f steam to the heating o f

botanic hothouses, we may refer to the garden of Messrs. Loddiges at Hackney, and that

of the Duke of Northumberland at Syon House. Both are veiy complete of then- kind,

and, having been executed for several years, may be considered as fully proving the superiority

of steam, on a large scale, to the former mode of heating by flues, though it is

very inferior to hot water. The steam apparatus at Syon House was erected under the

direction of the late eminent engineer, Mr. Tredgold, and, it may safely be affirmed, is the

most complete apparatus of the kind any where in existence.

2124. Steam w ill he fo u n d the most convenient mode o f heating garden structures under

the following circumstances :—Where the hothouses or pits arc numerous and scattered

about on different levels: where the object is chiefly to heat beds of soil; and generally,

wherever there are inteiwening spaces, that do not require warning between the

structures to be heated. The reason why steam is preferable to smoke-flues for this

purpose is, that these flues will not circulate smoke and hot air to any great distance;

and the reason why steam is preferable to hot water under the boiling point, is of a

similar natm-e. The reason why steam is preferable to hot water under compression,

by which, as will bo afterwai'ds shown, it is cu-culated at from 50 to 100 degrees above

the boiling point, is, that too much heat will be lost in the space between the structm-cs

to be heated.

2125. One o f the most ecmom ical modes o f a p p lying steam to the heating o f liothouses

is to apply it to a bed or mass of loose stones. This mode appeai-s to have been first

adopted by Mr. Hay, of Edinburgh, in 1807, and has been subsequently^applied by the

same eminent garden architect to a number of pine and melon pits in different parts of

Scotland. It was also adopted in England, and on a very extensive^ scale, in connection

with heating pipes and cisterns of water, at the nm-sery of Miller and Co. at

Bristol. Nothing can be more simple than this mode of applying steam. The bed of

stones to be heated may be about the usual thickness of a bed of tan or dung the

stones may be from 3 to 6 inches in diameter, hard round pebbles being preferred, as

less liable to crumble by moisture, and having larger vacuities between. The pipe for

the steam is introduced at one end of the bottom of this bed, and is continued to the

opposite end. It is uniformly pierced with holes along the two sides, so as to admit of

the equal distribution of the steam through the mass of stones, ‘i'he steam-pipe may be

of any dimension, it being found that the only difference between a large pipe aud a small

one is, that the steam proceeds fi-om the latter witli greater rapidity. The steam only

requires to be'introduced once in twenty-four hours in the most severe weather, and in

mild weather, once in two or three days is found sufficient. After the steam is turned

on, it is kept in that state till it has ceased to condense among the stones, and, consequently,

has heated them to its own temperature. This is known by the steam escaping,

either through the soil over the stones, or through the sides of the pit; or when a mass

of stones is enclosed in a case of masonry, as in the stone flues of the Bristol nursci-y, the

point of saturation is known hy the safety valve of the boiler being raised. When wc

consider the small-sized pipes that may be used for conveying and delivering steam by

this mode of its application, there can be no doubt that this is the cheapest mode of heating

on a large scale known; and it has also the advantage of never requiring to be

applied oftener than once in the twenty-four hours, and thus rendering all night-work

unnecessary.

2126. S tothe rt’s ap p lication o f steam to heds o f stones is given in detail in tho H o rtic u ltu

ra l Transactions, 2d scries, vol. i., and may be thus abridged.

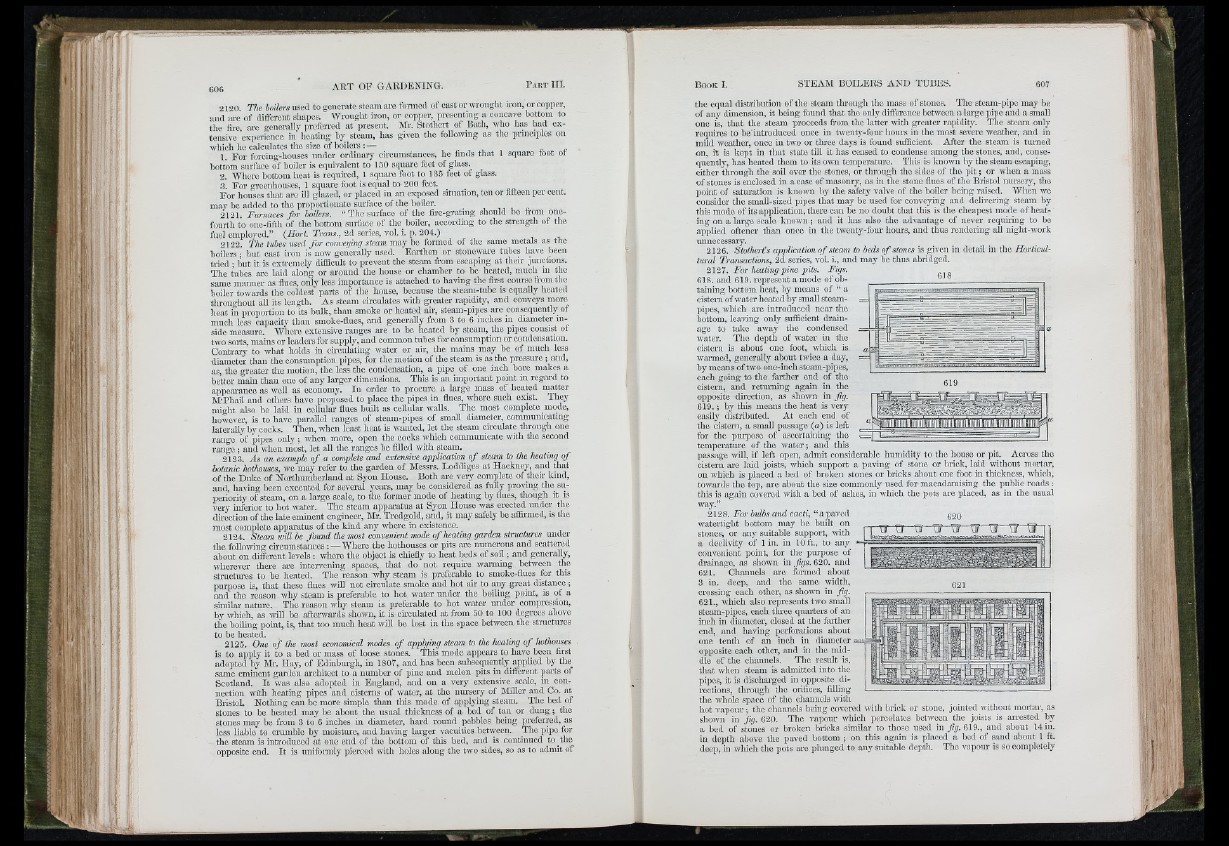

2127. F o r heating p ine p its . F ig s.

618. and 619. represent a mode of ob-

taining bottom heat, by means of “ a

cistci-n of water heated by small steam-

pipes, which arc introduced near the

bottom, leaving only sufficient drainage

to take away the condensed

water. The depth of water in the

cistern is about one foot, which is

warmed, generally about twice a day,

by means of two one-inch steam-pipes,

each going to the farther end of the

cistern, and returning again in the

opposite direction, as shown in fig .

619.; by this means the heat is very

easily distributed. At each end of

the cistern, a small passage (a) is left

for the purpose of ascertaining the

temperature of the water; and this

passage will, if left open, admit considerable humidity to the house or pit. Aci-oss the

cistern ai-e laid joists, wliich support a paving of stone or brick, laid without mortar,

on which is placed a bed of broken stones or bricks about one foot in thickness, which,

towards the top, arc about the size commonly used for macadandsing the public roads :

this is again covered with a bed of ashes, in wliich the pots are placed, as in the usual

way.”

2128. F o r h ulh sa n d cacti, “apaved

watertight bottom may be built on

stones, or any suitable support, with

a declivity of 1 in. in 10 ft., to any

convenient point, for the purpose of

drainage, as shown in fig s. 620. and

621. Channels are foi-med about

3 in. deep, and tho same width,

crossing each other, as shoavn in fig .

621., which also represents two small

steam-pipes, each tliree quai-ters of an

inch in diameter, closed at the farther

end, and having perforations about

one tenth of an inch in diameter a

opposite each other, and in the middle

of the channels. The result is,

that when steam is admitted into the

pipes, it is discharged in opposite directions,

through the orifices, filling

the whole space of the channels with

hot vapour; the channels being covered with brick or stone, jointed without mortal-, as

shown in fig . 620. Tho vapour which percolates between the joists is an-ested by

a bed of stones or broken bricks similar to those used in fig . 619., and about 14 in.

in depth above tho paved bottom ; on this again is placed a bed of sand about 1 ft.

deep, in wliich the pots are plunged to any suitable depth. The vapour is so completely