•» I

Division ii. Gardening in China, in respect to its horticidtural Productions.

795. On the firs t view o f the coast o f China, says Mr. Main, “ the stranger concludes

that the inliabitants arc a nation of gardeners. Even the fields, in the southern provinces,

are almost all cultivated by manual labour, aud every thing shows the indefatigable

industry of the cultivators. On entering the mouth of Canton river, and having

ascended to the Bocca Tigris (an old Portuguese name for a fortified part of the

river), the hanks begin to collapse, and to present to the exploring eye of the botanist

thcir vegetable productions. He secs the general surface of the country, a level,

widely-extended, and well-cultivated plain, intersected in all directions by navigable

canals ; diversified hy abrupt and craggy hills, scattered here and there over the face of

the country. Within and around the grotesque yet airy habitations which hang suspended,

as it were, over the sedgy margin of the river, are seen magnolias, ixoras, chrysanthemums,

&c. in great profusion. After an interesting passage up the river, tho

stranger enters the suburbs of the city. Hero he is surprised to sec the number of

flowers aud flowering plants which every where meet his eye : every house, window,

and court-yard are filled with them !” (Gard. Mag., vol. ii. p. 135.)

796. Horticulture in China is generally considered to be in an advanced state ; but

wc have no evidence that the Chinese are acquainted with its scientific principles, and

especially with tho physiology of plants. The climate and soil of so immense a

tract as China are necessarily various ; and equally so, in consequence, the vegetable

productions. Besides the fruits peculiar to the country, many of wliich arc unknown to

the rest of the world, it produces the greater part of those of Europe ; but, except the

oranges and pomegranates, they are much inferior.

79L The fru its cultivated in China, accordmg to Mr. Main, are the following :— tho

grape, the pomegranate, two sorts of peaches, several sorts of plums, two sorts of pears,

many varieties of oranges, &c., of cucumbers and melons, the chestnut, the capsicum,

the avcrrlioa, the plantain, the guava, the gourea, five sorts of dimocarpus, thè jujube,

the date palm, the loquat, the kisurachu, and the packlam.

798. The edible roots, according to the same authority, are the following : — the common

potato, lately introduced, tho sweet potato (Convolvulus Batàtas), the yam, tlic

beet, tho carrot, the onion, garlic, three or four sorts of water-lily, four or five sorts of

arums, turnips, radishes, ginger, turmeric, and bamboo.

799. Edible leaves:— beet, cabbage, two or three sorts, lettuces, endive, spinach, tea,

olive, O'lca fràgrans, and .^maraiitus. The last plant is used as spinach, and the leaves

of the O'lca fràgrans like those of tea.

800. Pods :—peas, beans, water-lily seeds, rice, maize, and several other sorts of grain.

801. Fruits in China are “ so plentiful,” says Dobell, who visited the country in 1830,

“ that there is less attention paid to tlicm than in colder climates. Almost every month

of the year lias its peculiar fniits ; but those most esteemed arc the oranges, mangoes,

and litcliis. They have pears of various sorts, peaches, plums, pine-applcs, watermelons,

bananas, plantains, longans, wampees, guavas, jacks, shaddocks, grapes, figs,

&c. Ill the height of the season an orange costs only a cash or two, but it is always

peeled, the rind being more valuable, for medicinal, purposes, &c., than ihe orange

itself. The sellers arc remarkably expert at peeling them. Fruits ai*c sold on stalls in

every street ; the prices ai*e ofttimcs marked on a piece of bamboo, so that tho buyer

can go and eat of what he likes, throw down his money on the stall, and walk off

without uttering a single word. Vegetidiles are sold in the same manner, or cried

through the streets ; but they are generally weighed. The buyer weighs for himself

with his own ti/chin or steelyard, which he can-ies with him, and the seller weighs after

him, to sec that he is correct. In the a rt of cultivating vegetables the Chinese are not

to be equalled ; ancl at Macao there are as fine potatoes and cabbages as in any part of

the world. Potatoes do not succeed so well at Canton ; but, as the Chinese are not

fond of them, tliis is doubtless owing more to the want of care than the diffei-ciice of

climate, in a distance of only ninety miles. (Travels, ^c., vol. ii. p. 317.)

802. In the cultivation o f culinary vegetables o f all sorts, the Chinese are not to be

surpassed by any nation of the globe. Whoever has visited Whampoa must have seen

a striking proof of this assertion in tlie gardens, which adorn the steep sides of hills of

Dane’s and French Islands, wliere they rise in regular gradation, like a flight of stairs,

from the bases to the summits of the hills. I t must cost immense pains to cultivate

them ; and to water them, as the Chinese do, at least twice a day. These gardens

exliibit, in the strongest manner, the persevering industi-y of the inhabitants, and delight

the beholder with a rich vegetation, clotlicd in various shades of the liveliest verdure.

(Ibid., vol. ii. p. 193.)

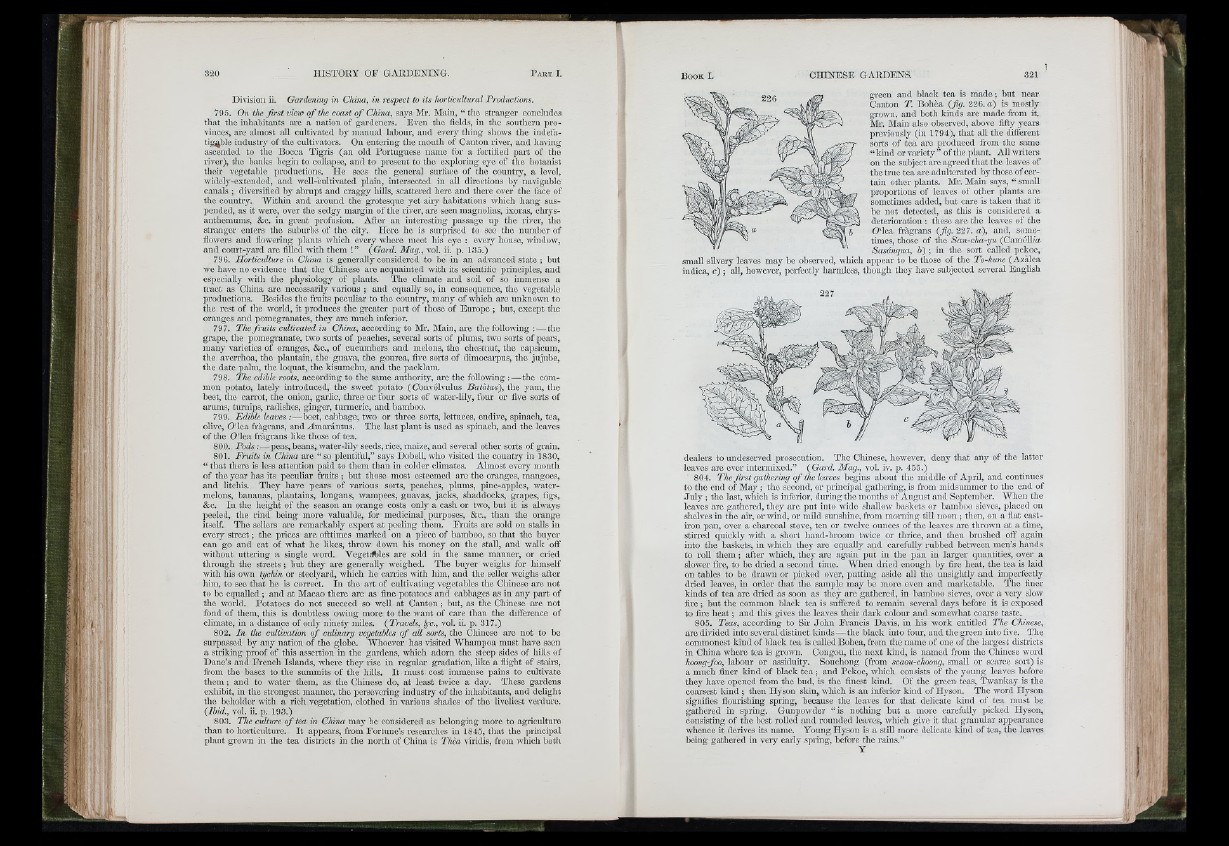

803. The culture o f tea in China may he considered as belonging more to agriculture

than to horticulture. It appears, from Fortune’s researches in 1845, that the principal

plant grown in the tea districts in the north of China is Th'ea viridis, from wliich botli

green and black tea is m a d e ; but near

Canton T. Bohea (fig. 226. a ) is mostly

grown, and both kinds arc made from it.

Mr. Main also observed, above fifty years

previously (in 1794), tliat all the diflcrent

sorts of tea arc produced from the same

“ kind or variety ” of the plant. All writers

on the subject arc agreed th a t the leaves of

the true tea arc adulterated hy those of certain

other plants. Mr. Main says, “ small

proportions of leaves of other plants are

sometimes added, but care is taken that it

bo not detected, as this is considered a

deterioration ; these are the leaves of the

O'lea fragrans (fig. 227. a), and, sometimes,

those of the San-cha-yu (Caméllia

Sasánqua, b) ; in the sort called pekoe,

small silvery leaves may be observed, which appear to be thoso of the To-kune (Aziilca

indica, c) ; all, however, perfectly harmless, though they have subjected several English

dealers to undeserved prosecution. The Chinese, however, deny that any of the latter

leaves are ever intermixed.” (Gard. Mag., vol. iv. p. 455.)

804. The firs t gathering o f the leaves begins about the middle of April, and continues

to the end of M a y ; the second, or principal gathering, is from midsummer to the end of

Ju ly ; tlie last, whicli is inferior, during the months of August and September. Wlien the

leaves arc gathered, they arc put into wide shallow baskets or bamboo sieves, placed ou

shelves iu the air, or wind, or mild sunshine, from morning till noon ; then, on a flat cast-

iron pan, over a charcoal stove, ten or twelve ounces of the leaves are thrown at a time,

stiiTcd quickly with a short hand-broom twice or thrice, and then brushed oft' again

into the baskets, in which they ai-c equally and carefully rubbed between men’s hands

to roll th em ; after whieh, they are again put in the pan in larger quantities, over a

slower fire, to be dried a second time. When dried enough by fire heat, the tea is laid

on tables to he drawn or picked over, putting aside all the unsightly and impci-fectly

dried leaves, in order that the sample may he more even and marketable. The finer

kinds of te a arc dried as soon as they ai-e gathered, in bamboo sieves, over a very slow

fire ; but the common black tea is suffered to remain several days before it is exposed

to fire h e a t; and this gives the leaves thcir dark colour and somewhat coai-se taste.

805. Teas, according to Sfr John Francis Davis, in his work entitled The Chinese,

arc divided into several distinct kinds— the black into foiu-, and the green into five. The

commonest kind of black tea is called Bohea, ii-om the name of one of the largest districts

in China where tea is grown. Congou, the next kind, is named from the Chinese word

koong-foo, labour or assiduity. Souchong (from scaou-choong, small or scai-ce sort) is

a much finer kind of black te a ; and Pekoe, which consists of the young leaves before

they have opened from the bud, is the finest kind. Of the green teas, TVankay is the

coai-scst kind ; then Hyson skin, which is an inferior kind of Hyson, The word Hyson

signifies floui-ishing spring, because the leaves for that delicate kind of tea must be

gathered in spring. Gunpowder “ is nothing hut a more carefully picked Hyson,

consisting of the best rolled and rounded leaves, which give it that granular appearance

whence it derives its name. Young Hyson is a still more delicate kind of tea, the leaves

being gathered in voi-y early spring, before the rains.”