U i

i J

I f e ito ■ b

1000 r.uïT III.

always be purchased, recourse must very I'requently be had to Cynosùrus cristàtus, Anthoxànthum

odoratum, and the common perennial rye grass, carefully avoiding the Dactylis glomerata, ifólcus mollis

and H . lanàtus, .ffròmus, &c., which are coarse grasses, and the seeds of which are very frequently found

mixed with those of rye grass and other species in th e seed shops. (See E n c y c . o f A g r ., § 5593. to 5713.)

.5027- Gra ssy surfac e s raay he formed by cutting tu rf in small pieces about 2 in. square, and distributing

them a t regular distances, say a t about 6 in. apart every way, over a well-prepared surface.

The practice is of old standing, but has been lately brought again into notice in Norfolk. ( See S in c la ir 's

U o rt. G ram . Wub., anà E n c y c . o f A g r ., § 5714. to 5716.)

5028. To r ep a ir a n d im p ro v e law n s in tow n s o r cities, o r u n d e r the shade o f trees, w ith o u t the a id o f

tu r f, dig the soil to the depth of 3 in. or 4 in. the last week in March or the first week in April, and

afterwards sow it thickly and regularly with the following seeds: — ^Igróstis vulgàris var. tenuifòlia,

FWiàciiduriuscula, F. ovina, Cynosùrus cristàtus, P òa pratènsis, .ivèna flavéscens, and Trifòlium m inus.

These seeds must be mixed together in equal portions, and sown a t the rate of from four to six bushels

per acre. If the seeds are regularly and thickly sown, the ground will soon become green, and will

remain as close and thick as any tu rf whatever during the whole summer ; dying, however, in the succeeding

winter, and requiring, therefore, to be revived every spring.

5029. Wa te r. This material, in some form or other, is as essential to th e flower as to th e kitchen

garden. Besides the use of the element in common culture, a pond or basin affords an opportunity of

growing some of th e more showy aquatics, while jets, drooping fountains, and other forms o f displaying

water, serve to decorate and give interest to th e scene. Besides choice aquatics, the ponds or basins of

flower-gardens may be stocked with the gold-flsh.

5030. T h e fo rm o f a small garden ( fig . 8-53.) will be found most pleasing when some regular figure is

adopted, as acircle, an oval, an octagon, a crescent, &c. : but

where the extent is so great as not readily to be caught by a

•single glance of the eye, an irregular shape is generally more

convenient, and it maybe thrown into agreeable figures, or component

scenes, by the introduction of shrubs so as to subdivide

th e space. “ Either a square or an oblong ground-plan,”

Abercrombie observes, “ is eligible ; and although the shape

must be often adapted to local circumstances, yet, when a garden

is so circumscribed, that the eye at once embraces the

whole, it is desirable that it should be of some regular figure.”

.5031. N ico l says, “ a variety of forms may be indulged in,

without incurring censure ; provided the figures be graceful,

and not in any one place too complicated. An oval is a figure

th a t generally pleases, on account of the continuity of its outlines

; next, if extensive, a circle. Next, perhaps, a segment

in form of a half-mooii, or the larger segment of an oval. But

hearts, diamonds, triangles, or squares, if small, seldom please.

A simple parallelogram, divided into beds running lengthwise,

or th e larger segment of an oval, with beds running parallel

to its outer margin, will always please.” Neill concurs in this

opinion.

5032. The a u th o r o f H in ts on the Foi-mation o f G ardens, &c.,

says, “ a symmetrical form is best adajited to such parterres

as are small and may be comprehended in one view ; and an

irregular shape to such as are of a considerable size, and contain

trees, shrubs, statues, vases, seats, and buildings.”

5033. B o u n d a r y , fe n c e , o r screen. Parterres on a small scale

may be enclosed by an evergreen hedge of holly, box. laurel,

privet, juniper, laurustinus, or Irish whin ( i/'lo x hibernica) ;

but irregular figures, especially if of some extent, can only

be surrounded by shrubbery, .-»uch as we have already hinted

(5022.), as forming a proper shelter for flower-gardens.

•5034. Abercrombie says, “ for the enclosure, a wall or close

paling is, on two accounts, to be preferred on the north side ;

both to serve as a screen, and to afford a warm internal face for training ra re trees. When cne of those

is not adopted, recourse may be had to a fence of whitethorn and holly,” 8cc. (P ra c t. G a rd ., 339.)

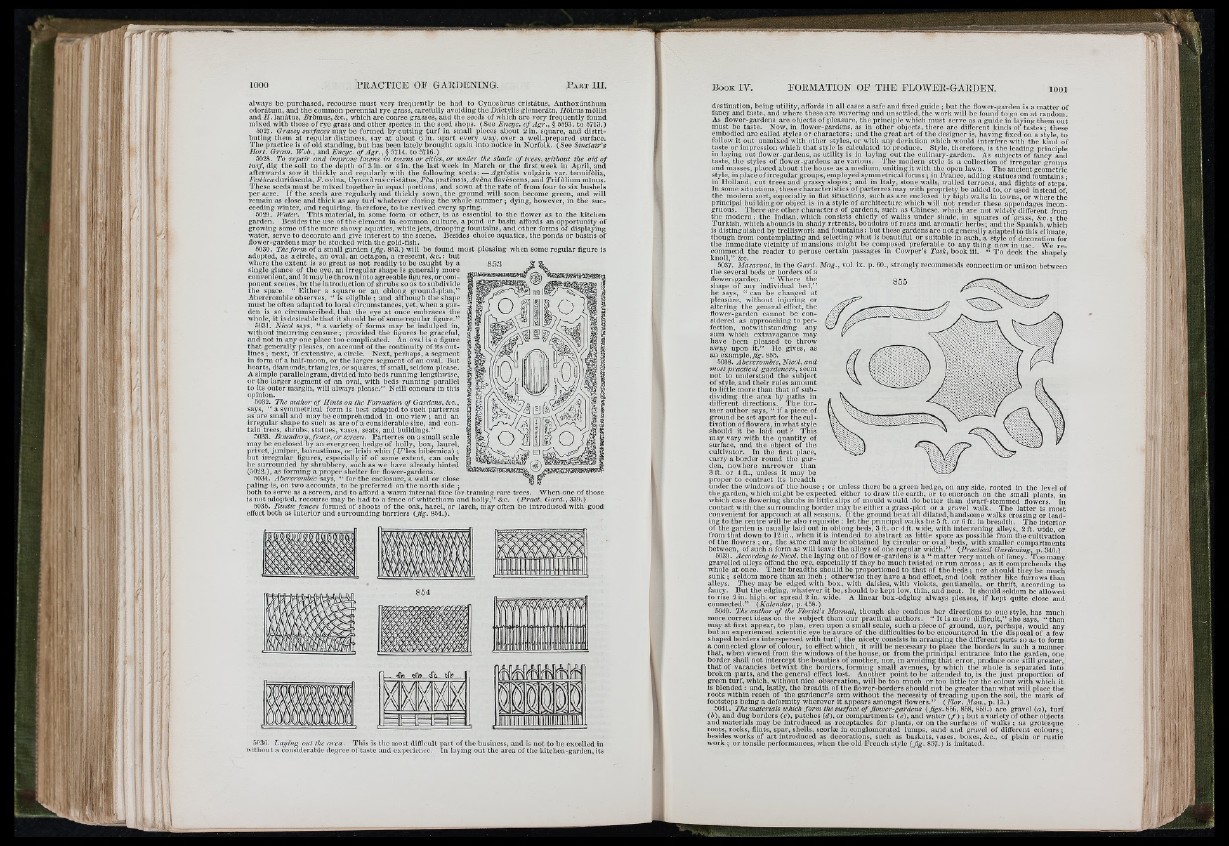

■5035. R u s tic fe n c e s formed of shoots of th e oak, hazel, or larch, may often be introduced with good

effect both as interior and surrounding barriers (J ig. 854.).

B o o k IV.

■5036. L a y in g o ut the a r e a . This is the most difficull part of the business, and is not to be excelled in

w ithout a considerable degree of taste and experience. In h-iying out the area of the kitchen-garden, its

destination, being utility, aflbrds in all c.ases a safe and fixed guide ; but the flower-garden is a matter of

fancy and taste, and where these are wavering and unsettled, the work will be found to go on at random.

As flower-gardens are objects of pleasure, the principle which must serve as a guide in l.Tving them out

must be taste. Now, in flower-gardens, as in other objects, there are difi'erent kinds o f tastes ; these

embodied are called styles or characters ; and tho great a rt of the designer is, having fixed on a style, to

follow it out unmixed with other styles, or with .any deviation which would interfere with the kind of

taste or impression which th a t style is calculated to produce. Style, therefore, is the leading principle

in laying out flower-gardens, as vitility is in laying out the culinary-garden. As subjects of fancy and

taste, the styles of flower-gardens are various. The modern stylo is a collection of irregular groups

and masses, placed about the house as a medium, uniting it with the open lawn. The ancient geometric

style, in place o firregular groups, employed symmetrical forms ; in France, adding statues and fountains ;

in Holland, cut trees and grassy slopes; and in Italy, stone walls, walled terraces, and flights of steps.

In some situations, these characteristics of parterres may with propriety be added to, or used instead of

the modern sort, especially in flat situations, such as are enclosed by high walls in towns, or where thè

principal bui Iding or object is in a style of architecture which will not render these appendages incongruous.

There are other character s of gardens, such as Chinese, which are not widely different from

the modern ; the Indian, which consists chiefly of walks under shade, in squares of grass, &c. ; the

Turkish, which abounds in shady retreats, boudoirs of roses and aromatic herbs; and the Spanish, which

is distinguished by trelliswork and fountains : but these gardens are not generally adapted to this climate

ihough from contemplating and selecting what is beautiful or suitable in each, a style of decoration for

the immediate vicinity of mansions might be composed preferable to any thing now in use. We recommend

the reader to peruse certam passages in Cowper’s T a sk , book iii. “ To deck th e shanelv

knoll,” &c.

5037. Masaroni, in the Ga rd . M a g ., vol.ix. p. 60., strongly recommends connection or unison between

the several beds or borders of a

flower-garden. “ Where the

shape of any individual bed,”

he says, “ can be changed at

pleasure, without injuring or

altering the general effect, the

flower-garden cannot be considered

as approaching to perfection,

notwithstanding any

sum which extravagance may

have been pleased to throw

aw_ay upon it.” He gives, as

an example,j%. 855.

5038. Abercrombie, N icol, a n d

m o st p ra c tic a l gardenia's, seem

not to understand th e subject

of style, and their rules amount

to little more than th a t of subdividing

the area by paths in

different directions. The former

author says, “ if a piece of

ground be set apart for the cu ltivation

of flowers, in what style

should it be laid o u t? This

may vary with the quantity of

surface, and the object of the

cultivator. In the first place,

carry a border round the garden,

nowhere narrower than

3 ft. or 4 ft., unless it may be

proper to contract its breadth

under the windows of the house ; or unless there be a green hedge, on any .side, rooted in the level of

the garden, which might be expected either to draw the earth, or to encroach on the small plants, in

which case flowering shrubs in Httle slips of mould would do better than dwarf-stemmed flowers. In

contact with the surrounding border may be either a grass-plot or a gravel walk. T h e latter is most

convenient for approach at all seasons. If the ground b e a t all dilated, handsome walks crossing or leading

to the centre will be also requisite : let th e prmcipal walks be 5 ft. or 6 ft. in breadth. The interior

of th e garden is usually laid out in oblong beds, 3 ft. or 4 ft. wide, with intervening alleys, 2 ft. wide, or

from th a t down to 12 in., when it is intended to abstract as little space as possible from th e cultivation

of the flowers ; or, the same end may be obtained by circular or oval beds, with smaller compartments

between, of such a form as will leave the alleys of one regular width.” (P ra c tic a l Gard en in g , v>. 340.)

5039. Ac cording to Nicol, the laying out of flower-gardens is a “ matter very much of fancy. Too many

gravelled alleys offend th e eye, especially if they be much twisted or run across ; as it comprehends the

whole a t once. Their breadths should be proportioned to th a t of th e beds ; nor should they be much

sunk ; seldom more than an inch ; otherwise they have a bad effect, and look ra the r like furrows than

alleys. They may be edged with box, with daisies, with violets, gentianella, or thrift, accordmg to

fancy. But th e edging, whatever it be, should be kept low, thin, and neat. It should seldom be allowed

to rise 2 in. high, or spread 2 in. wide. A linear box-edging always pleases, if kept quite close and

connected.” (K a le n d a r , p. 458.)

5040. T k e a u th o r o f the F lo rist's M a n u a l, though she confines her directions to one style, has much

more correct ideas on the subject than our practical authors. “ It is more difficult,” she says, “ than

may a t first appear, to plan, even upon a small scale, such a piece of ground, nor, perhaps, would any

but an experienced scientific eye be aware of the difficuUies to be encountered in the disposal of a few

shaped borders interspersed with tu rf ; th e nicety consists in arranging the different parts so as to form

a connected glow of colour, to effect which, it will be necessary to place the borders in such a manner

that, when viewed from the windows of the house, or from the principal entrance into the garden, one

border shall not intercept the beauties of another, nor, in avoiding th at error, produce one still greater,

th a t of vacancies betwixt the borders, forming small avenues, by which the whole is separated into

broken parts, and th e general effect lost. Another point to be attended to, is the ju st proportion of

green turf, which, without nice observation, will be too much or too little for the colour with which it

is blended : and, lastly, the breadth of the flower-borders should not be greater than w hat will place the

roots within reach of the gardener’s arm without th e necessity of treading upon th e soil, the mark of

footsteps being a deformity wherever it appears amongst flowers.” (F lo r . M a n ., p. 13.)

5041. T h em a te r ia ls which fo rm th e su ifa c e q f flow e r -g a rd e n s ( f ig s . 866, 8.58, 859.) are gravel (a ) , tu rf

(b ), and dug borders (c), patches (d ), or compartments (e ), and water ( / ) ; but a variety of other objects

and materials may be introduced as receptacles for plants, or on the surfaces of walks ; as grotesque

roots, rocks, flints, spar, shells, scoriæ in conglomerated lumps, sand and gravel of different colours ;

besides works of a rt introduced as decorations, such as baskets, vases, boxes, &c., of plain or rustic

work ; or tensile performances, when the old French style (Jig. 857.) is irailated.