’ ii i '

ré ! ■

¡q. ...

t I

and maintain a more interesting expression, they must be regarded as injurious ratlier

than beautiiul. „ , , . ■ vi - ^

1539 B a t siniplicitu and nature, continually repeated, become tiresome in their turn,

and man is then pleased to recognise the hand of art, if judiciously exercised even on an

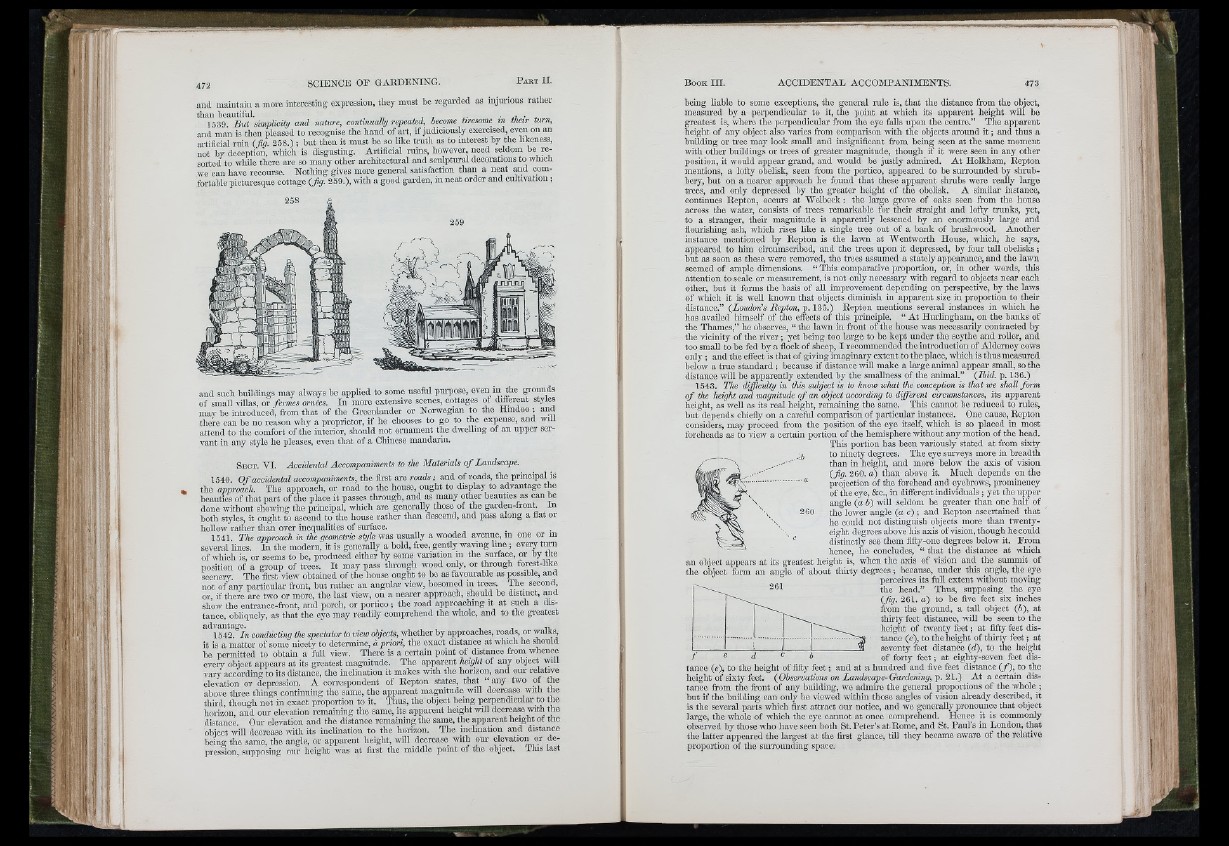

artificial ruin (Jig. 258.) ; hut then it must be so like truth as to interest hy the likeness,

not by deception, which is disgusting. Artificial ruins, however need seldom be resorted

to while there arc so many other architectural and sculptm-al decorations to which

we can have recourse. Nothing gives more general satisfaction than a neat and comfortable

picturesque cottage (fig. 259.), ivitli a good gai*den, in neat order and cultivation ;

258

and such buildings may alwavs be applied to some useful purpose, even m the gi-ounds

of small villas, or fermes ornées. In more extensive scenes, cottages of dffierent styles

mav be introduced, from that o f th e Greenlander or Norwegian to the Hindoo; and

there can be no reason why a proprietor, if he chooses to go to the expense, and will

attend to the comfort of the interior, should not oraament the dwelling of an upper servant

in any style he pleases, even that of a Chinese mandarin.

S e c t . VI. Accidental Accompaniments to fhe Materials o f Landscape.

\ 540. O f accidental accompaniments, the first are roads ; and of roads, the principal is

the approach. The approach, or road to the house, ought to display to advantage the

beauties of that part of the place it passes through, and as many other beauties as can be

done without showing the prmcipal, which are generally those of the garden-front. In

both styles, it ought to ascend to the house rather than descend, and pass along a flat or

hollow rather than over inequalities of surface.

1541 The approach in the geometric style was usually a wooded avenue, in one or in

several lines. In the modern, it is generally a bold, free, gently waving line ; eveiy turn

of which is, or seems to be, produced either by some vana.tion in the surface, or by the

position of a group of trees. I t may pass through wood only, or through fqrest-like

sceneiy. The first view obtained of the house ought to be as favourable as possible, and

not of any particular front, but rather an angular view, bosomed in trees. The second,

or if there arc two or more, the last view, on a nearer approach, should he distinct, and

show the entrance-front, and porch, or portico ; the road approaching it at such a distance,

obliquely, as that the eye may readily comprehend the whole, and to the gi-eatest

advantage. , , , i i n

1542. In conducting fhe spectator to view objects, whether by approaches, roads, or walks,

it is a matter of some nicety to determine, à priori, the exact distance at which he should

be permitted to obtain a fuU view. There is a certain point of distance from whence

every object appears at its greatest magnitude. The apparent height of any object will

vary according to its distance, the inclination it makes with the horizon, and our relative

elevation or depression. A conrespondent of Repton states, that “ any two qf the

above three things continuing the same, the apparent magnitude will decrease with the

third, though not in exact proportion to it. Thus, the object being perpendicular to the

horizon, and our elevation remaining the same, its apparent height will decrease with the

distance. Our elevation and the distance remaining the same, the apparent height ot the

object will decrease with its inclination to the horizon. The inclination and distance

being the same, the angle, or apparent height, will decrease with onr elevation or depression,

supposing our height was at first the middle point of the object. Ih is last

ACCIDENTAL ACCOMPANIMENTS. 473

being liable to some exceptions, the general mle is, that the distance from the object,

measm*ed hy a pei-pendicular to it, the point at which its apparent height will be

greatest is, where the pei-pendicular from the eye falls upon the centre.” The apparent

height of any object also varies from comparison with the objects around i t ; and thus a

building or tree may look small and insignificant from being seen at the same moment

with other buildings or trees of greater magnitude, though if it were seen in any other

position, it would appear grand, and would be justly admired. A t Holkham, Repton

mentions, a lofty obelisk, seen from the portico, appeared to be surrounded hy shrubbery,

but on a nearer approach he found that these apparent shrubs were reaUy large

trees, and only depressed by the greater height of the obelisk. A similar instance,

continues Repton, occm-s at Welbeck: the lai-ge grove of oaks seen from the house

across the water, consists of trees remarkable for their straight and lofty trunks, yet,

to a stranger, their magnitude is apparently lessened hy an enormously large and

flomishiiig ash, which rises like a single tree out of a bank of brushwood. Anothei-

instance mentioned by Repton is the lawn at Wentworth House, which, he says,

appeared to him circumscribed, and the trees upon it depressed, by four tall obelisks;

but as soon as these were removed, the trees assumed a stately appearance, and the lawn

seemed of ample dimensions. “ This comparative proportion, or, in other words, this

attention to scale or measurement, is not only necessary with regard to objects near each

other, but it forms the basis of all improvement depending on perspective, by the laws

of which it is well known that objects diminish in apparent size in proportion to their

distance.” (Loudon’s Bepton, p. 135.) Repton mentions several instances in which he

has availed himself of the effects of this principle. “ A t Hurhngham, on the hanks of

the Thames,” he observes, “ the lawn in front of the house was necessarily contracted by

the vicinity of the riv e r; yet being too large to be kept under the scythe and roller, and

too small to be fed by a flock of sheep, I recommended the introduction of Alderney cows

o n ly ; and the effect is that of giving imaginary extent to the place, wliich is thus measured

below a true stan d a rd ; because if distance will make a large animal appear small, so the

distance will be apparently extended by the smallness of the animal.” (Ibid. p. 136.)

1543, The difficulty in this subject is to know what fhe conception is that we shall fo im

o f tke height and magnitude o f an object according to different circumstances, its apparent

height, as well as its real height, remaining the same. This cannot be reduced to rules,

but depends chiefly on a careful comparison of particular instances. One cause, Repton

considers, may proceed fi-om the position of the eye itself, which is so placed in most

foreheads as to view a certain portion of the hemisphere without any motion of the head.

This portion has been vai-iously stated at from sixty

to ninety degrees. The eye surveys more in breadth

than in height, and more below the axis of vision

(fig. 260, d) than above it. Much depends on the

projection of the forehead and eyebrows, prominency

of the eye, &c., in different individuals; yet the upper

angle (a b) wiU seldom be gi-eater than one h alf of

the lower angle (a c) ; and Repton ascertained that

he could not distinguish objects more than twenty-

eight degi-ces above his axis of vision, though he could

distinctly see them fifty-one degrees below it. Erom

hence, he concludes, “ that the distance at which

an object appears at its greatest height is, when the axis of vision and the summit of

the object form an angle of about thirty degrees; because, under this angle, the eye

perceives its full extent without moving

the head.” Thus, supposing the eye

(fig. 261. a ) to he five feet six inches

from the ground, a tall object (b), at

thirty feet distance, will he seen to the

height of twenty feet ; at fifty feet dis-

’leheig’

260

261

I i

tance (c), to the height of thirty fe e t; at

seventy feet distance (d), to the height

of forty fe e t; at eighty-seven feet dis-

hundred and five feet distance ( / ) , to the

■-Gardening, p. 21.) At a certam disr

e d

tanco (e), to the height of fifty fe e t; and at í

height of sixty feet. (Observations on Lands ^ ,

tance from the ft-ont of any building, we admire the general proportions of the whole ;

but if the building can only be viewed within those angles of vision already described, it

is the several parts which first attract our notice, and we generally pronounce that object

large, the whole of which the eye cannot at oncc comprehend. Hence it is commonly

observed by those who have seen both St, Peter’s at Rome, and St. Paul’s in London, that

the latter appeared the largest at the first glance, till they became aware of the relative

proportion of the sm-rounding space.

r é .