Í ;

j i ?

otH ; ir é

growing on soil with an injurious substratum, could the pnming-knife be applied to

thcir descending and diseased roots annually, the advantages would be considerable. The

practice of laying bare the roots of trees to expose them to the frost, and render the tree

fruitful, is mentioned by Evelyn and other writers of his time; but in doing so, it does

not appear that pruning was any part of their object. The pruning of roots can therefore

only take place, according to the present state of things, in the interval between

taking up and replanting. • As such roots arc generally small, and some of tlicm broken or

injured, all that the pruner has to do, is to facilitate the healing of the ends of broken

roots by a more perfect amputation; and in fruit-trees, he may shorten such roots as have

a tendency to strike too pei'pendicularly into the soil. The form of the cut in either case

is a matter of less consequence than in the shoot; but, like it, it ought in general to be

made from tlie under side of the shoot, that only one section may be fractured, and that

the removed section may be the fractured one; and also that water or sap may rather

descend from than adhere to tlie wound. The cliief reason for this practice, however, is

the facility of performing it ; for a section directly across, as if made irith 'a saw, will, in

roots, heal as soon, if not sooner, than one made obliquely; but to make such a section

in even small roots would require several distinct cuts, whereas the oblique section is

completed by a single operation. The Genoese gardeners, in pruning the roots of the

orange ti-ees, always make a section directly across, which, in one yeai-, is in great part

covered by the protmding granulated matter. (See 2318.)

2562. T he roots o f trees m ight be completehj pruned, i f done hy degrees; say that tho

roots extend in every direction in the form of a circle; then take a portion, say one

eighth, of that circle every year till it is completed, and remove the earth entirely from

above and under the roots; then cut off the diseased parts, or those roots which penetrate

into bad soil, aud laying below them such a stratum as to be impenetrable in future,

intermix and cover them with suitable soil.

2563. P ru n in g herbaceous p lan ts, or what is called trim m ing , consists generally in

thinning the stems to increase the size and flowers of those which remain; but it may

also be performed for all the pui-poses before mentioned ; and for some other pui-poses,

such as the prolongation of the lives of annuals by pinching off their blossoms,

strengthening bulbous roots by tlie same means, increasing the lowcr leaves of the

tobacco-plant by cutting over the stem a few inches above ground, &c. In trimming

the roots of herbaceous plants, the same general principles ave adopted as in pnmiug

the roots of trees. In transplanting seedlings, the tap-root merely requires to be

shortened ; and in most other cases, only bmiscd, diseased, or broken roots are cut off,

and fractured sections smoothed.

2564. T h e seasons f o r p ru n in g trees are generally winter and midsummer; but some

authors prefer spring, following the order of the vegetation of the different species and

varieties. According to this principle, the first pruning of fi-uit-trees begins in February

with the apricot, then the peach, afterwards the pears and plums, then the cherries,

and lastly the apples, tho sap of which is not properly in motion till April. Some

have recommended the autumn and raid-winter; but though this may be allowable in

forest trees, it is certainly injurious to tender trees of every sort, by drying and hardening

a portion of wood close to the part cut, and hence the granulous matter does not so

easily protrude between the bark and wood, as in trees where those parts are furnished

with sap. For all the operations of pmning, therefore, which are performed on the

branches or shoots of trees, the best period appears to be that immediately before, or

commensurate with, the rising of the sap.

2565. S um m er p ru n in g commences with disbudding, or the rubbing off of the buds,

soon after they have begun to develope their leaves in April and May ; and is continued

during summer hy pinching off or sliortening such as ai-c farther advanced. It is

obviously, to a certain extent, guided by tlie same general rules as winter or general

pnining; but the great use of leaves in preparing the sap being considered, summer

pnming wisely conducted wUl not extend farther than may be neccssai-y to maintain as

much as possible au equilibrium of sap among the branches, to prevent gom-mands and

water-shoots from depriving the fruit of proper nom-ishmcnt, and to admit sufficient air

and light to the fruit. Most authors are of opinion that the other objects of pruning

will be better effected by winter operations. Summer pruning is chiefly applicable to

fruit-trees, and among these to the peach; but it is also practised on forest and ornamental

trees when young, and is of great importance in giving a proper direction to the

sap in newly gi-afted trees in the nursery.

2566. T h in n in g the branches of individual trees may be considered as included in

.pruning. In herbaceous vegetables, or young trees growing together in quantities, it

consists in removing all such as impede the others from attaining tho desfrcd bulk, form,

or other properties fur which they arc specially cultivated ; and it is generally performed

in connection with weeding or hoeing.

Su b se ct. 4. T ra in in g .

2567. B y tra in in g is to be understood the conducting of the shoots of trees or plants

over the surface of walls, espalier rails, trellises, or on any other flat surface. It is performed

in a variety of ways, according to the kind of tree, the object in view, and the

particular opinions of gardeners.

2568. T he object o f tra in in g is, either to induce a disposition to form flowcr-buds iu

rare and tender trees or plants; to mature aud improve the quality of fruits which would

not otherwise ripen in the open air; or to increase the quantity and precocity of the fmit

of trees which mature thcir fmit in the open air. Such arc the principal objects of

training; vliich are effected by the shelter and exposure to the sun of the surface to

which the trees ai-e trained, by which more heat is produced, ancl injm-ies from severe

weather better guarded against; by the regular spreading of the branches on this surface,

by which the leaves are more fully exposed to the sun than they can be on any standard;

and by the form of training, which, by retai-ding the motion of the descent of the sap,

causes it to spend itself in the formation of flowcr-buds.

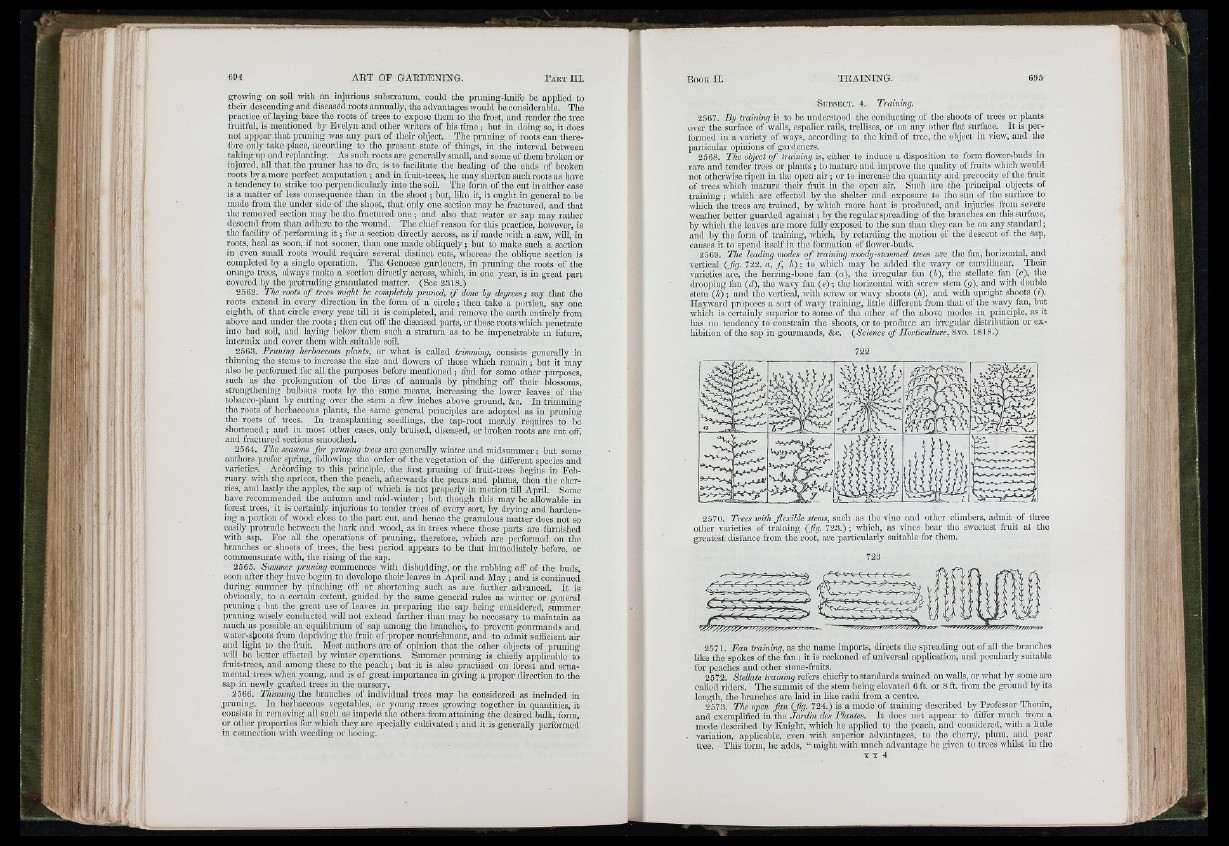

2569. T he leading modes o f tra in in g woody-stemmed trees are the fan, horizontal, and

vertical (fig . 722. a , f h ) ; to which may be added the wavy or curvilinear. Thcir

vai-icties are, the herring-bone fan (a), the in-egular fan (6), the stellate fan (c), the

drooping fan (d ), the wavy fan (e) ; the horizontcti with screw stem (g ), and with double

stem (Ji) ; and the vertical, with screw or wavy shoots (Ji), and with upright shoots (J).

Hayward proposes a sort of wavy training, little different from that of the w<yy fan, but

which is certainly superior to some of the other of the above modes in principle, as it

has no tendency to constrain the shoots, or to produce an irregular distribution or exhibition

of the sap in gourmands, &c. (Science o f H o rtic u ltu re , Svo. 1818.)

722

2570. Trees w ith Jl.exible stems, such as the vine and other climbers, admit of three

other varieties of training (fig . 723.); which, as vines bear the sweetest fruit at the

greatest distance from the root, are particularly suitable for them.

2571. F a n tra in in g , as tho name imports, directs the spreading out of all the branches

like the spokes of the fan ; it is reckoned of universal application, and peculiarly suitable

for peaches and other stone-fruits.

2572. S tellate tra in in g refers chiefly to standards trained on walls, or what by some arc

called riders. The siunmit of the stem being elevated 6 ft. or 8 ft. from the ground by its

length, the branches arc laid in like radii from a centi-c.

2573. T he open fa n (fig . 724.) is a mode of training described by Professor Thouin,

and exemplified in the J a rd in des P lantes. It does not appear to differ much from a

mode described by Knight, which he applied to the peach, and considered, with a little

variation, a])plicable, even with superior advantages, to the cherry, plum, and_ pear

tree. This form, he adds, “ might with much advantage be given to trees wliilst in the

Y Y 4

i n

;

ta)

J i M

? ' « i l l

. i- ‘ ' ''•'■’Íj

'1 1 ; Í '