■ I f»:(i

■ 'fc

5042. R o c kw o rk s. T h e author of th e F lo rist's M a n u a l observes, on this subject, th a t “ fragments of

stone may be made use of, planted with such roots as flourish among rocks, and to which it might not

be difficult to give a natural appearance, by suiting the kind of stone to th e plant which grows naturally

among its débris. The present fashion

of introducing into flower-gardens

this kind of rockwork requires the

hand of taste to assimilate it to our

flower-borders, the massive fabric of

th e rock being liable to render the

lighter assemblage of the borders diminutive

and meagre : on this point

caution only can be given, the execution

must be left to th e elegant eye

of taste, which, thus warned, will

quickly perceive such deformity. I

must venture to disapprove of the extended

manner in which this mixture

of stones and plants is sometimes introduced,

not having been able to

reconcile my eye, even in gardens

planned and cultivated with every advantage

which elegant ingenuity can

give them, to the unnatural appearance

of artificial crags of rock and

other stones interspersed with delicate

plants, to the culture of which

the fertile and sheltered border is evidently necessary, being decided that nothing of the kind should be

admitted into the simple parte rre th a t is not manifestly of use to th e growth of some of the species

therein exhibited. In pleasure-grounds or flower-gardens on an extensive scale, where we meet with

foimtains and statuary, the greater

kinds of garden rockwork might pro- 8 5 9

bably be well introduced ; but to such

a magnificent display .of a rt I feel my

taste and knowledge wholly incompetent.”

{F lo r . M a n ., p .15.) “ W here

neither expense nor trouble,” the

same author adds, “ oppose their prohibitory

barrier,manyof the vegetable

tribe may be cultivated to greater

perfection, if we appropriate different

gardens to the growth of different

SDOcies ; as, although it is essential to

th e completion of our garden to introduce,

on account of their scent and

beauty, some of th e more hardy spe-

cies of the flowers termed annuals, in

th a t situation room cannot be afforded

them sufficient to th e ir production in that full luxuriancy which they will exhibit when not crowded and

overshadowed by herbaceous vegetables ; and hence becomes desirable th a t which may be called the

annual flower-garden, into which no other kind of flower is admitted besides th a t fugacious order, and

under which is contained so great a variety of beauty and elegance, as one well calculated to form a

garden, vying in brilliancy with the finest collection of hardy perennials. Also, th e plants comprised

under th e bulbous division of vegetables, although equally essential to th e perfection of the mingled

flower-garden, lose much of their peculiar beauty when not cultivated by themselves, and will well repay

the trouble of an assiduous care to give to each species the soil and aspect best suited to its nature. Two

kinds of garden may be formed from the extensive and beautiful variety of bulbous-rooted flowers ; the

first, wherein they should be planted in distinct compartments, each kind having a border appropriated

to Itself, thus forming, in the Eastern taste, not only the ‘ garden of hyacinths,’ but a garden of each

species of bulb which Is capable of being brought to perfection without the fostering shelter of a conservatory.

The second bulbous garden might be formed from a collection of th e almost infinite variety

of this lovely tribe, the intermixture of which might produce th e most beautiful effect, and a succession

of bloom to continue throughout th e early m onths of summer. A similar extension of pleasure might

be derived from a similar division of all kinds of flowers, and here the taste for borders planted with distinct

tribes may be properly exercised, and, as most of the kinds of bulbs best suited to this disposition

have finished their bloom before th e usual time a t which annuals disclose their beauties, the annual and

the bulbous gardens might be so united, th a t, a t the period when the bloom of the latter has disappeared,

the opening t

6043. The greenhouse o r c o n s e r v a to r y 'is g en e ra lly plac ed v>

)uds of the former might supply its place, and continue the gaiety of the borders.”

co se rva ry is generaUy in tk e fiow e r -g a rd en , provided these structures

.re not appended to the house. In laying out the an ,

are area,a fit situation must be allotted for, this

tment the

iry 2829.)require here also to be applied Some recommend the distribution of the

department of floriculture, and th e principles of guidance laid down in treating of the situation of the

culinary hothouses (28'-' ' ' ' ^ ..................................... ® .....................................

botanic hothouses thrc

pie

that much the best effect i:. .

theymayforra objectsagreeab)

beauties, it appears to us that they m ust be examined in succession and without interruption. Noarrangi.

ment can be better, in our opinion, than to connect the whole of the botanic hothouses with the mansion

as an introductory scene to the flower-garden.

5044. A ccording to NeiU, a greenhouse, conservatory, and stove should form prominent objects in the

different parts of the flower-garden. The author of th e F lo rist's M a n u a l recommends a spring-conserva-

tory, annexed to the house, consisting of borders sheltered by glass, and heated only to the degree that

will produce a temperature, under which all th e flowers that would naturally bloom betwixt th e months

of February and May might be collected, and thence be enabled to expand their beauties with vigour.

{Flor. M a n ., - p .n . )

504-5. A ccording to Nicol, “ the most proper situation for the greenhouse and conservatory, in an extensive

and well laid out place, is certainly in the shrubbery or flower-garden ; and not as they are very

generally to be found, in the kitchen-garden, combined with the forcing-houses. In smaller places, no

doubt, they must be situated so as to suit other conveniences; and we often find them connected with the

dwelling-house. In this latter way they may be very convenient, especially in th e winter season, and may

answer for keeping many of the hardy kinds of exotics; but it is seldom they can be so placed and constructed,

on account of their connection with the building, as to suit the culture of the finer sorts, and

bring them to a flowering state. Such may ra the r be termed green-rooms, as being connected with the

house.” {K a len d a r,

5046. A bercrombie says, “ a greenhouse m ay b e made a very ornamental object as a stru ctu re : its

situation is, therefore, usually in a conspicuous part of the pleasure-ground, contiguous to the family residence.

The front of the building should stand directly to the south, and the ends have an open aspect to

th e cast and west.” {P ra c t. Ga rd ., p. 657.)

5047. F lo io e r-n u rse ry , a n d p i t s f o r fo r c in g fim o e r s . T o every complete flower-garden and shrubbery,

a piece of ground should be set apart in a convenient and concealed situation, as a reserve-ground, or

nursery of flowering plants and shrubs. T h e situation should, if practicable, be behind and near to the

range of hothouses, and it may a t th e same time include the pits for forcing flowers, and the hotbed

department of the flower-garden. Here plants may be originated from seed, cuttings, pipings, and a

proper stock kept up, partly in beds and partly in pots, for more easy removal, to supply blanks, and in

the more select scenes, to replace such as

have done flowering. No fiower-garden 8 6 0

can be kept in complete order without

nursery of this description ; nor could the

management of some sorts of florists’

flowers, as the auricula, during th e latter

part of summer and winter, th e carnation,

&c., be well carried on without it. Here

they may be grown, and, when in bloom, exhibited

in proper stages in the main garden.

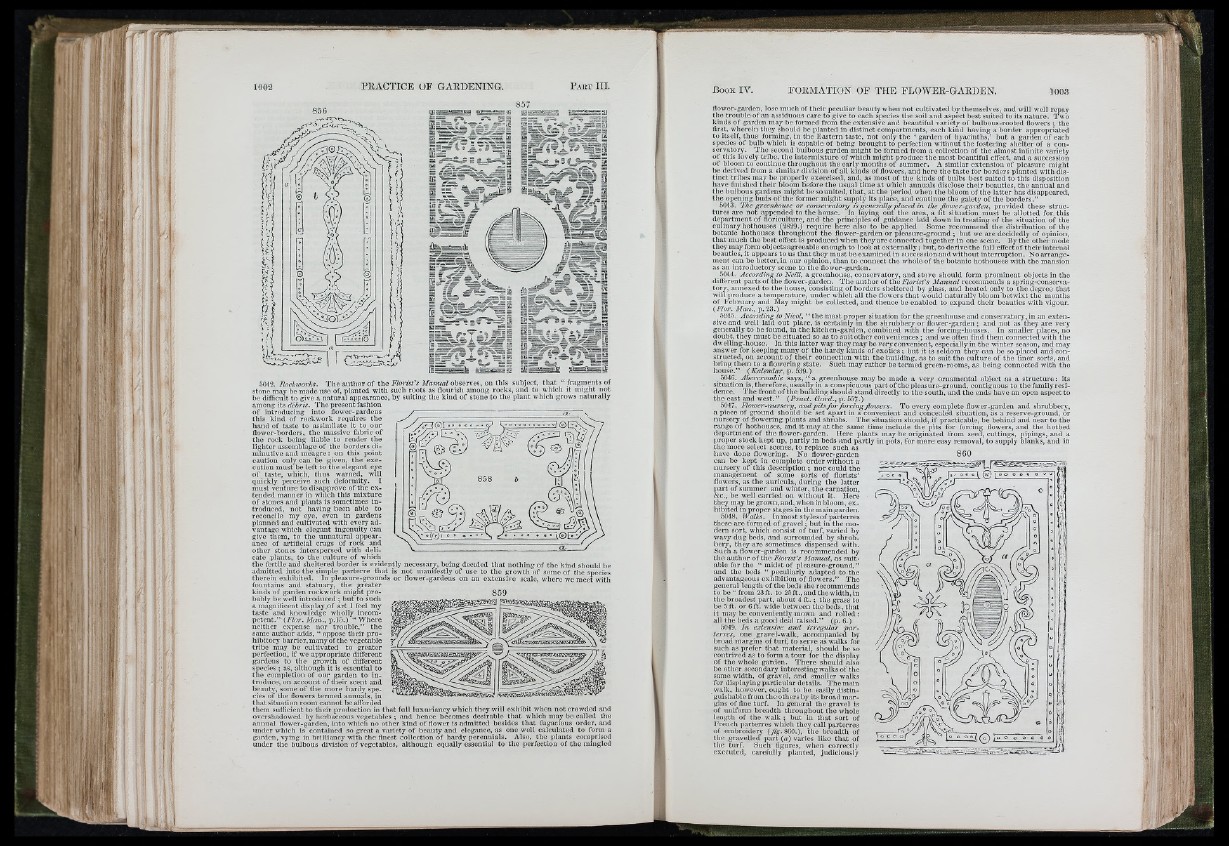

6048. W a lk s. Inmost stylesof parterres

these are formed of g ra v e l; but in the modern

sort, which consist of turf, varied by

wavy dug beds, and surrounded by shrub,

bery, they are sometimes dispensed with.

Such a flower-garden is recommended by

the author of the F lo rist's M a n u a l, as su itable

for the “ midst of pleasure-ground,”

and th e beds “ peculiarly adapted to the

advantageous exhibition of flowers.” The

general length of the beds she recommends

to be “ from 23ft. to 2.5ft.,and th ewidth,in

the broadest part, about 4 ft. ; th e grass to

be 5 ft. or 6 ft. wide between th e beds, that

it may be conveniently mown and ro lle d :

all the beds a good deal raised.” (p. G.)

5049. I n e x tensive a n d ir r e g u la r p a r te

r r e s , one gravel-walk, accompanied by

broad margins of turf, to serve as walks for

such as prefer that material, should be so

contrived as to form a tour for th e display

of the whole garden. T h ere should also

be other secondary interesting walks of the

same width, of gravel, and smaller walks

for displayingparticular details. T h e main

walk, however, ought to be easily distin-

guishable from the others by its broad mar-

gins of fine turf. In general the gravel is

of uniform breadth throughout the whole

length of the walk ; hut in th a t sort of

French parterres which they call parterres

of embroidery {fig .% m .), the breadth of

the gravelled part {a) varies like that of

the turf. Such figures, when correctly

executed, carefully planted, judiciously

S i