render them more prominent ; and small groups (¿>), here and there in th e recesses, to varv th cir forms

and conceal their real depths. •'

5832. In all plantations in ih c natural style above tb e size o i a groxxp, the same general principles are

to be followed in the disposition of the trees ; the plants, whatever be their kinds, and whetlier the mass

IS finally to assume the character of a wood, grove, or copse, should be placed irregularly • here thick

and there thin, ns if they had sprung up from th e accidental semination of birds or winds The effect

of this arrangement will not be that composition of low and high, oblique and upright stems, and young

and old trees, and low growths, which we find in forest scenery ; but it is all th a t can be done in imitation

of It a t the first planting ; and subsequent thinning, pruning, and cutting down, moving, rmversing

planting, and sowing, must be used from time to time to complete imitation or allusion, unless the owner

will rest satisfied with an inferior degree of beauty.”

5833. The general fo rm o f tree employed materially influences the effect of plantations. The capacities

of different trees for producing effects in landscape, and the general division of trees into round-headed

oblong-headed, and spiry-topped, have been already pointed out. It has also been observed that thè

greater number of plantations are seen chiefly in profile ; and hence, that the outline which the tons of

th e trees form against the sky or th e background, is the most conspicuous feature in their aspect The

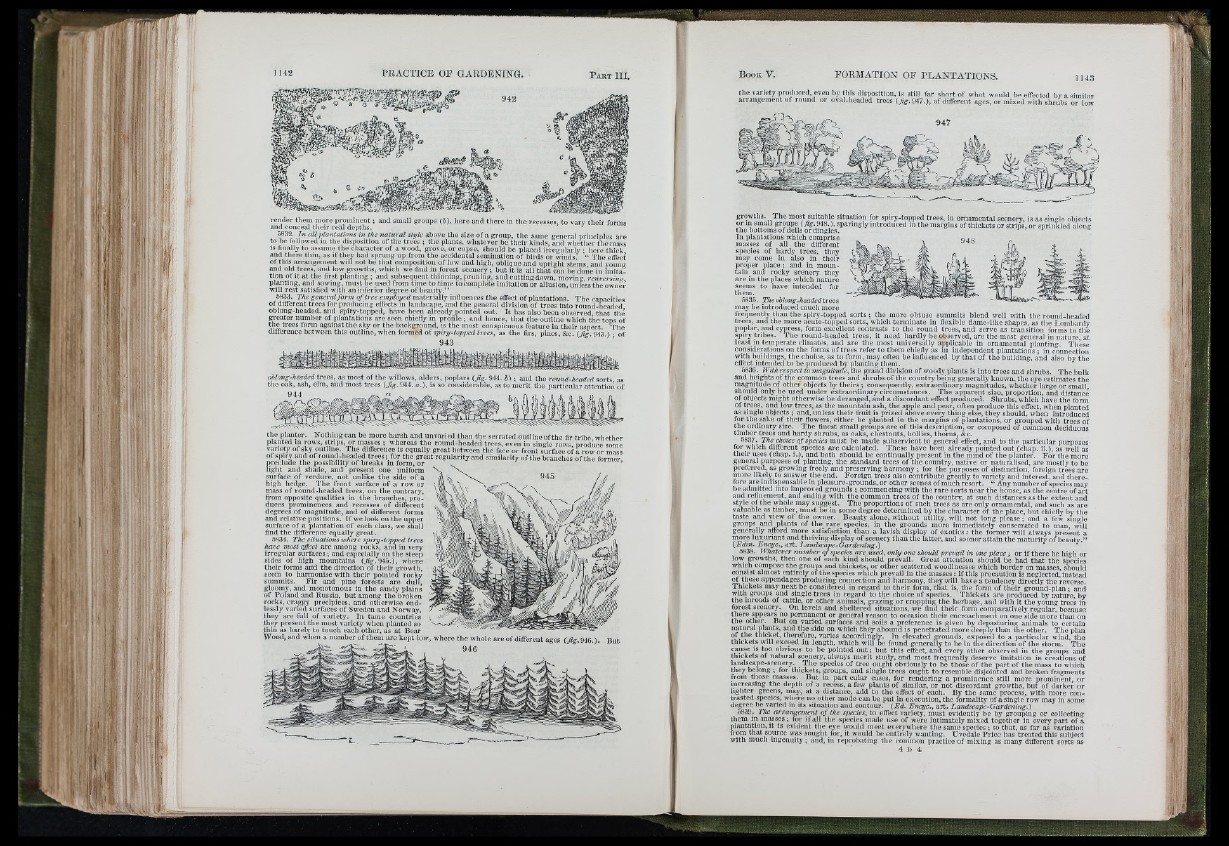

difference between this outline, when formed of spiry-topped trees, as the firs, pines, &c. (fig. 9 4 3 .) ; of

943

ohlong-headed trees, as most of th e willows, alders, poplars (fig. 944. 6) ; and the round-headed sorts as

th e oak, ash, elm, and most trees (fig. 944. a.), is so considerable, as to merit the particular attention of

the planter. Nothing can be more harsh and unvaried than the serrated outline ofthe flr tribe whether

planted m rows, strips, or masses ; whereas th e round-headed trees, even in single rows, produce some

variety of sky outline. The difference is equally great between tho face or front surface of à row or mass

of spiry and of round-headed trees ; for th e great regularity and similarity of the branches of the former,

preclude the possibility of breaks in form, or ** vi,

light and shade, and present one uniform

surface of verdure, not unlike th e side of a

high hedge. The front surface of a row or

mass of round-headed trees, on the contrary,

from opposite qualities in the branches, p ro.

duces prominences and recesses of different

degrees of magnitude, and of different forms

and relative positions. If we look on th e upper

surface of a plantation of each class, we shall

find th e difference equally great.

5834. The situations where spiry-topped trees

have most effect are among rocks, and in very

irregular surfaces ; and especially on the steep

sides of high mountains (fig. 945.), where

their forms arid th e direction of their growth,

seem to harmonise with their pointed rocky

summits. F ir and pine forests are dull,

gloomy, and monotonous in the sandy plains

of Poland and Russia, but among th e broken

rocks, craggy precipices, and otherwise endlessly

varied surfaces of Sweden and Norway,

they are full of variety. In tame countries

they present the most variety when planted so

thin as barely to touch each other, as a t Bear

Wood, and when a number of them are kept low, where th e whole are of different ages (fig . 946.). But

946

the variety produced, even by this disposition, is still fa r short of what would be effected bv a similar

arrangement of round or oval-headed trees ( / g . 947.), of different ages, or mixed with shrubs or low

growths. The most suitable situation for spiry-topped trees, in ornamental scenery, is as single objects

or m small groups ( / g 948.), sparingly introduced in the margins of thickets or strips, or sprinkled along

th e bottoms of dells or dingles. i » r =

In plantations which comprise

masses of all the different p. ,V “ ( a

species of hardy trees, they A m ,

may come in also in their

proper p la c e ; and in mountain

and rocky scenery they

are in th e places which nature

seems to have intended for

them.

5835. TheobloTig-headedtrees

may be introduced much more

frequently than the spiry-topped s o rts ; the more obtuse summits blend well with th e round-headed

trees, and the more acute-topped sorts, which terminate in flexible flame-like shapes, as the Lombardy

poplar, and cypress, form excellent contrasts to the round trees, and serve as transition forms to the

spiry tribes. The round-headed trees, it need hardly be observed, are the most general in nature, at

least m temperate climates, and are th e most universally applicable in ornamental planting. These

considerations on the forms of trees refer to them chiefly as in independent plantations ; in connection

with buildings, the choice, as to form, may often be influenced by that of the building, and also by the

effect intended to be produced by planting them.

5836._ With respect to magnitude, the grand division of woody plants is into trees and shrubs. The bulk

and hmghts of the common trees and shrubs of the country being generally known, the eye estimates the

magnitude of other objects by theirs ; consequently, extraordinary m agnitudes, whether large or small

should only be used under extraordinary circumstances. The apparent size, proportion, and distance

of objects might otherwise be deranged, and a discordant effect produced. Shrubs, which have the form

of tree s, and low trees, as the mountain ash, th e apple and pear, often produce this effect, when planted

as single objects ; and, unless their fruit is prized above every thing else, they should, when introduced

for the sake of their flowers, either be planted in the margins of plantations, or grouped with trees of

th e ordinary size. The finest small groups are of this description, or composed of common deciduous

timber trees and hardy shrubs, as oaks, chestnuts, hollies, thorns, &c.

5837. The choice o f species must be made subservient to general effect, and to the particular purposes

for which different species are calculated. These have been already pointed out (chap. ii.), as well as

their uses (chap. i.), and both should be continually present in the mind of the planter. F o r the more

general purposes of planting, the standard trees of the country, native or naturalised, are mostly to be

preferred, as growing freely and preserving harmony ; for the purposes of distinction, foreign trees are

more likely to answer the end. Foreign trees also contribute greatly to variety and interest, and there-

fore are indispensable in pleasure-grounds, or other scenes of much resort. “ Any number of species may

be admitted mto improved grounds ; commencing with the ra re sorts near the house, as th e centre of a rt

and refinement, and ending with th e common trees of th e country, a t such distances as the extent and

style of the whole may suggest. The proportions of such trees as are only ornamental, and such as are

valuable as riraber, must be in some degree determined by the character of the place, but chiefly by the

taste and view of the owner. Beauty alone, without utility, will not long p lea se; and a few single

groups and plants of the ra re species, in the grounds more immediately consecrated to man, will

generMly attord more satisfaction than a lavish display of exotics: the former will always present a

more luxuriant and thriving display of scenery than th e latter, and sooner attain the m aturity o fbeauty.”

(jbdtn. Encyc., art. Landscape-Gardening.)

.5838. Whatever number o f species are used, only one should prevail in one place ¡ or if there be high or

low growths, then one of each kind should prevail. Great attention should be had that the species

which compose the groups and thickets, o r other scattered woodinesses which border on masses, should

consist almost entirely of the species which prevail in the masses: if this precaution is neglected, instead

of these appendages producing connection and harmony, they will have a tendency directly the reverse

Thickets may next be considered In regard to their form, th a t is, the form of their ground-plan : and

with groups and single trees in regard to the choice of species. Thickets are produced by nature by

th e inroads of cattle, or other animals, grazing or cropping th e herbage, and with it the young trees in

forest scenery. On levels and sheltered situations, we find th eir form comparatively regular, because

there appears no permanent or general reason to occasion their encroachment on one side more than on

th e other. But on varied surfaces and soils a preference is given by depasturing animals to certain

natural plants, and the side on which they abound is penetrated more deeply than th e other. The plan

of the thicket, therefor^ varies accordingly. In elevated grounds, exposed to a particular wind, the

thickets will exceed m length, which wiil be found generally to be in the direction of the storm. The

cause is too obvious to be pointed o u t ; b u t this effect, aiiá every other observed in the groups and

thickets of natural scenery, always merit study, and most frequently deserve imitation in creations of

landscape-scenery _ T h e species of tre e ought obviously to be those of the part of th e mass to which

they belong ; for thickets, groups, and single trees ought to resemble disjointed and broken fragments

from those masses. But in p a rt cular cases, for rendering a prominence still more prominent, or

increasing the depth of a recess, a few plants of similar, or not discordant growths, but of darker or

lighter greens, may, a t a distance, add to th e effect of each. By th e same process, with more contrasted

species, where no other mode can be pu t In execution, the formality of a single row may in some

degree be varied m its situation and contour. (Ed. Encyc., a rt. Landscape-Gardening.)

5839. Ik e arrangement of the species, to effect variety, must evidently be by grouping or collecting

them in masses ; for if all the species made use of were intimately mixed together in every part of a

Slaiitarion, it is evident the eye would meet everywhere the same species ; so that, as far as variation

•om that source was sought for, it would be entirely wanting. Uvedale Price has treated this subject

with much ingenuity; and, in reprobating the common practice of mixing as manr different sorts as

ito;;: I

M l'

to

to / ' ' i

■V

'/■ rél

I

i ' fl

: i t