39

¡ ? S r A t ¥ ¥ t o o u s a n d t e e t f o n g . T h e v o t a m e o f w a t e r i s f o u r f e e t w .d e b y

f Z f S Z f f ? u p 5 y ln 7 h ¥ l£ ¥ s " 7 S L s ''A t f e ° E ¥ g l* s h “ Acle™thAfi¥h-^^^^^^^ various jet’s d 'e a u ;

ri? ¥ e 5 from the garden-front of th e palace, or from th e middle entrance a rd i, through that long

djscu re portico or arcade which pierces tho whole depth of the quadrangle, and acts like the tube " f »

? d e ¥m a to th I waters " Is th a t of one continued sheet of smooth or stagnant water resting on a slope;

il- I f ifouSitain which had suddenly burst forth and threatened to inundate the plain ; but for this idea the

liu r s I r tU m ^ S ? is too tome, trL q u il, and regular, and it looks more 1 ke some artrficial 7 1 “ '™ <¡f

water than water itself. In short, th e effect is still more unnatural than it is

iets and fountains are also unnatural, yet they present nothing repugnant to our ideas

things • b u t a body of water seemingly reposing on a slope, and accommodating itself to the inclin^ion

of th e surface, is a sight at variance with th e laws of gravity. Unquestionably th e cascade at

is a grand obiect of itse lf; but the other cascades are so trifling, and so numerous, as in perspective, and

v\ew?d a ? a S n c H S this strange effect of continuity of surface. A* ^

is correct we refer to th e views of Caserta, which are got up by th e Neapolitan artists foj sale, had

these artists been able to avoid th e appearance in question, even by some departures from tru th , there

t S e no doubt they would not have liesitated to do so. A b ird’s-eye view of this canffi, in Vanvitelli s

work (Jig. 25.), gives but a very imperfect idea of the reality as seen from the surface of the ground, and

25

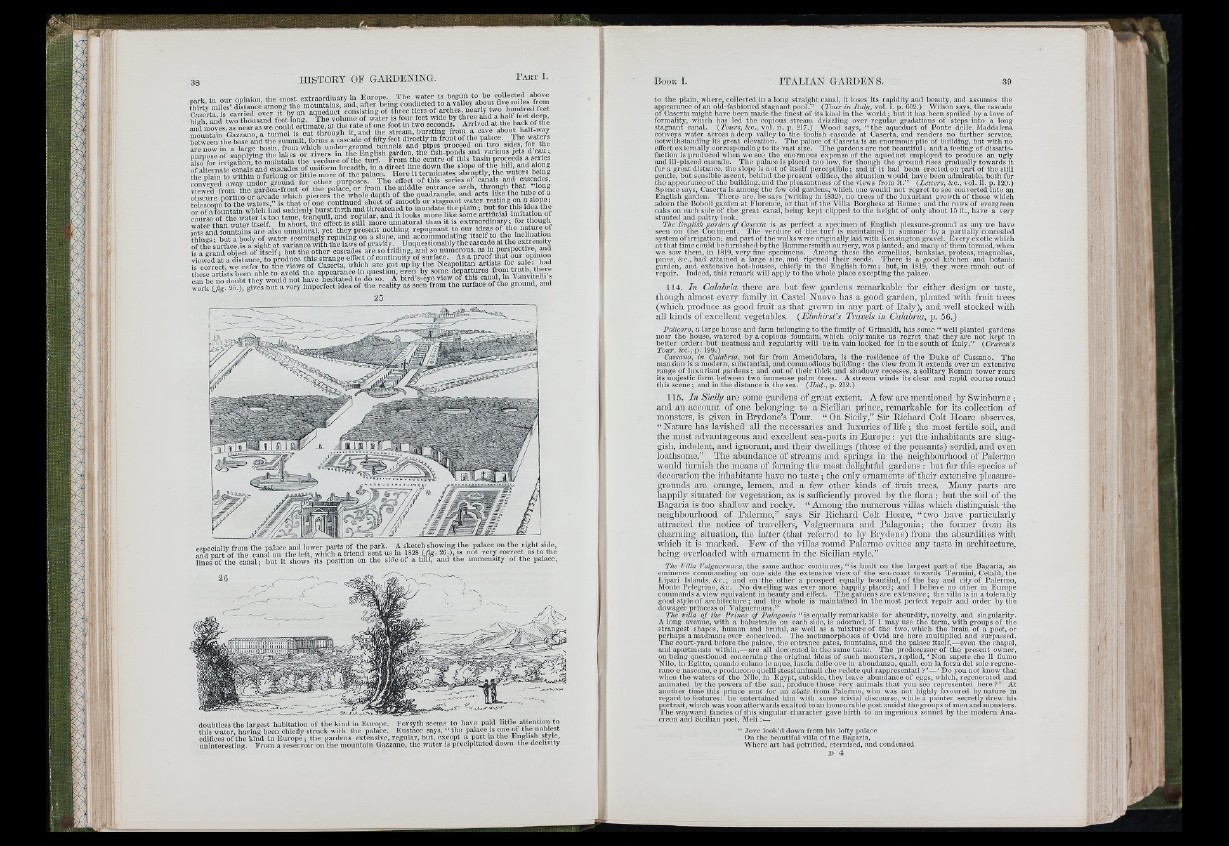

psneciallv from th e nalace and lower parts o f th e park. A sketch showing th e palace on th e right side,

S nart of th e caiiS on th e left, which a friend sent us in 1828 (Jig. 26.), is not very correct as to the

lines of th e canal; but it shows its position on the side of a hill, and th e immensity of the palace,

doubtless the largest habitation of the kind in Europe. Forsyth seems to have paid little a.ttention to

this water, having been chiefly struck with the palace. Eustace says, “ th e palace is one ot the noblest

edifices of th e kind in E u ro p e ; th e gardens extensive, regular, but, except a p a rt m the i'-nghsh j p m

uninteresting. From a reservoir on the mountain Gazzano, th e water is precipitated down the declivity

to the plain, where, collected in a long straight canal, it loses its rapidity and beauty, and assumes the

appearance of an old-fashioned stagnant pool.” (Tour in Italy, vol. i. p. 602.) Wilson says, the cascade

of Caserta might have been made the finest of its kind in the wo rld ; but it has been spoiled by a love of

formality, which has led the copious stream drizzling over regular gradations of steps into a long

faction is produced when we see the enormous expense of th e aqueduct emi

and ill-placed cascade. T h e palace is placed too low, for though the ground rises

iduce an ugly

^ . . . . . . . . . . . ._____„.. .... ^................ „....lually tow'sairdt s!

for a great distance, th e slope is not of itself p e r c ^ tib le ; and if it had been erected on p art of the still

gentle, but sensible ascent, behind the present edifice, the situation would have been admirable, both for

the appearance of the building, and the pleasantness of the views from it.” (Letters, Sec., vol. ii. p. 120.)

Spence says, Caserta is among the few old gardens, which one would not regret to see converted into an

English garden. There are, he says (writing in 1832), no trees of th e luxuriant growth of those which

adorn the Boboli garden a t Florence, or th a t of the Villa Borghese at Rome; and th e rows of evergreen

oaks on each side of th e great canal, being kept clipped to th e height of only about 15 ft., have a very

stunted and paltry look.

The English garden o f Caserta is as perfect a specimen of English pleasure-ground as any we have

A.-,. AUo TU.. .,..-.1,.-., c f eUc jjy ^ partially concealed

1 the Continent. The verdure of th e tu rf is maintained in summer .

system of irrigation; and part of th e walks were originally laid with Kensington gravel

ravel. Every exotic which

a t that time could be furnished bythe Hammersmith nursery, was planted; and

lany of them formed, when

( saw them, in 1819, very fine specimens. Among these the camellias, banksias, proteas, magnolias,

pines, &c., had attained a large size, and ripened their seeds. T h ere is a good kitchen and botanic

. garden, and extensive hot-houses, chiefly in the English form; but, in 1819, they were much out of

repair. Indeed, this remark will apply to the whole place excepting the palace.

114. In Calabria there are but few gardens remarkable for either design or taste,

though almost eveiy family in Castel Nuovo has a good garden, planted with fmit trees

(which produce as good fmit as that grown in any part of Italy), and well stocked with

all Idnds of excellent vegetables. {Elmhirsls Travels in Calabria, p. 56.)

Policoro, a large house and farm belonging to the family of Grimaldi, has some “ well planted gardens

near the house, watered by a copious fountain, which only make us regret th a t they are not kept in

b etter order: b u t neatness and regularity will be in vain looked for in th e south of Italy.” (Craven's

Tour, Sec., p. 199.)

Cassano, in Calabria, not far from Amendolara, is th e residence of th e Duke of Cassano. The

mansion is a m odern, substantial, and commodious building : th e view from it extends over an extensive

range of luxuriant gardens ; and out of their thick and shadowy recesses, a solitary Roman tower rears

its majestic form between two immense palm trees. A stream winds its clear and rapid course round

this scene; and in the distance is th e sea. (Ibid., p. 212.)

115. In Sicily are some gardens of great extent. A few are mentioned by Swinburne ;

and an account of one belonging to a Sicilian prince, remarkable for its collection of

monsters, is given in Brydone’s Tour. “ On Sicily,” Sir Richard Colt Hoai'e obsen'es,

“ N ature has lavished alï the necessaries and luxuries of life ; the most fertile soil, and

the most advantageous and excellent sca-ports in Exmope : yet the inhabitants are sluggish,

indolent, and ignorant, aud their dwellings (those of the peasants) sordid, and even

loathsome.” The abundance of streams and spxings in the neighbom'hood of Falenno

would fuinish the means of forming the most delightful gardens : but for this species of

decoration the inhabitants have no taste ; the only ornaments of thch- extensive pleasure-

grounds are orange, lemon, and a few other kinds of fiaiit trees. Many paits are

liappily situated for vegetation, as is sufficiently proved by the flora ; but the soil of the

Bagaria is too shallow and rocky. “ Among the numerous villas wliich distinguish -the

neighbourhood of Palermo,” says Sir Richai-d Colt Hoai-e, “ two have paxticularly

attracted the notice of travellers, Valguernara and Palagonia; the former from its

charming situation, tho latter (that refexTcd to by Brydone) from the absurdities with

which it is marked. Few of the villas roxmd Palermo erince any taste in architecture,

being overloaded with ornament in the Sicilian style.”

The Villa Valguernara, the same author continues, “ is built on the

of the Bagaria, i

eminence commanding on one side the extensive view of th e sea-coast towai

Termini, Cefalù, the

Lipari Islands, &c.; and on th e other a prospect equally beautiful, of th e bay and city of Palermo,

Monte Pelegrino, &c. No dwelling was ever more happily placed; and I believe no other in Europe

commands a view equivalent in beauty and effect. T h e gardens are extensive; the villa is in a tolerably

good style of a rch itectu re; and th e whole is maintained in the most perfect repair and order by the

dowager princess of Valguernara.”

The villa o f the Prince of Palagonia equally remarkable for absurdity, novelty, and singularity,

side, is adorned, if I may use th e term, with groups of the

Palagc

A lo n g avenue, with a balustrade on each s i d e , . . . . . . .. . .

strangest shapes, human and brutal, as well as a mixture of the two, which th e brain of a poet, or

perhaps a madman^ ever conceived. T h e metamorphoses of Ovid are here multiplied and surpassed.

T h e court-yard before the palace, the entrance gates, fountains, and th e palace itself,—even th e chapel,

and apartments within,—are all decorated in the same taste. T h e predecessor of the present owner,

on being questioned concerning the original ideas of such monsters, replied, ‘ Non sapete che il fiumo

Nilo, in Egitto, quando calano le aque, lascia delle ove in abondanza, quali, con la forza del sole regene-

rano e nascono, e producono quelli stessianimali che vedete qui rappresentati ? ’—‘Do you not know that

when th e waters of th e Nile, in Egypt, subside, they leave abundance of eggs, which, regenerated and

animated by the powers of the sun, produce those very animals th a t you see represented here ? ’ At

another time this prince sent for an abate from Palermo, who was not highly favoured bv nature in

regard to fe atures: he entertained him with some trivial discourse, while a painter secretly drew his

portrait, which was soon afterwards exalted to an honourable post amidst the groups of men and monsters.

T h e wayward fancies of this singular character gave birth to an ingenious sonnet by the modern Anacreon

and Sicilian poet, Meli : —

“ Jove look’d down from his lofty palace

On the beautiful villa of the Bagaria,

Where a rt had petrified, eternised, and condensed

I> 4