generally on the south-east side of the latter (ô), on a raised platform, the rising grounds

behind being planted botb for effect and shelter.

1555. The field o f vision, or portion o f landscape which the eye will comprehend, is a

cfrcmnstance frequently mistaken in fixing a situation for a liouse ; since a view seen

from tbe windows of an apai-tment will materially differ from tbe same view seen in the

open afr. Much evidently depends on tbe thickness of tbe walls (fig. 267.), the width

1556. The aspect o f the principal rooms deserves pai'ticular attention in every case, and

most so in bleak or exposed situations. The south-east is most commonly the best for

268 h a d

of the windows (a), and tbe distance of 'the spectator from

tbe aperture. Near the centre of tbe room (6), the spectator

ivill not enjoy above 20 or 30 degrees of vision ; but

close to the window (c) his eye will take in from 70 to 100

dcgi'ees. Hence, to obtain as much cff the view from a

room as possible, there should not only be windows on two

sides of a room, but one in the angle, or an obbque or

bow-window on each side, instead of the common form.

(Obs. on Landscape-Gardening, p. 24.)

t/ooà

Britain 268.); and the south, and due

east, tbe next best. Tbe south-west, Repton

considers the worst, because from tbat quarter

it rains oftcner tban from any other ; and the

windows are dimmed, and tbe views obstructed,

by tbe slightest showers, which will not

be perceptible in the windows facing tbe south

or east. A north aspect is gloomy, because

deprived of sunsliine ; but it deserves to be

remarked, that woods and other verdant objects

look best when viewed from rooms so

placed, because all plants are most luxuriant

on the side next tbe sun. (Fragments on

Landscape-Gardening, &c., p. 108.)

1557. A mansion fo r the country, if a mere

square or oblong, will tbus be deficient in

point of aspect, and certainly in pictm-esque beauty, or variety of external forms, lighfr,

and shades. An irregular plan, composed witb a combined view to tbe situation, distant

views, best aspects to tbe principal rooms, effect from different distant points, and as

forming a whole ivitb the groups of domestic offices and other architectural appendages or

erections, will therefore be the best ; and, as tbe genius of tbe Gothic style of architec-

tui-e is better adapted for this irregularity than the simplicity of the Grecian, or the

regularity of tbe Roman styles, it bas been justly considered tbe best for country residences.

Another advantage of an irregulai- style is, tbat it readily admits of additions

in almost any direction.

1558. Convenience, as well as effect, requfre that every bouse ought to have an entrance-

front, and a garden-front ; and, iu general cases, neither the latter, nor tbe views fr-om

the principal rooms, should be seen fully and completely, but fi-om tbe windows and

garden-scenery. Not to attend to this, is to destroy tbeir contrasted effect, and cloy the

appetite, by disclosing all or the greatest pai't of the beauties at once. The landscape

which forms the backgi-ound to a mansion, tbe trees which group witb it, and the architectural

terrace which forms its base, are to be considered as its accompaniments, and

influenced more or less by its style. The classic pine and cedar should accompany the

Grecian and Roman architecture ; and tbe hardy fir, the oak, or tbe lofty ash, tbe baronial

castle.

1559. Ten-ace and conservatory. We observed, when treating of ground, and of the

ancient style, that tbe design of the terrace must be jointly influenced by tbe magnitude

and style of the „house, the views from its windows (that is, from the eye of a person

seated in tbe middle of the principal rooms), and the views of tbe bouse from a distance.

In almost every case, more or less of arclntectural form will enter into these compositions.

The level or levels ivill be supported partly by grassy slopes, but chiefly by stone walls,

harmonising witb tbe lines and forms of tbe bouse. Tbese, in the Gotlfic style, may

be fm-nished witb battlements, gateways, oriels, pinnacles, &c. ; or, on a vei-y gi-eat scale,

watch-towers may form very picturesque, characteristic, and useful additions. The

Grecian style may, in like manner, be finished by parapets, balustrades, and other Roman

appendages.

1560. The breadth o f terraces, and thefr height relatively to the level of the floor of tbe

living-rooms, must depend jointly on the height of the floor of tbe living-rooms and the

surface of the grounds or country to be seen over them. Too broad or too high a

terrace will botb have tbe effect of foreshortening a lawn with a declining surface, or of

concealing a near valley, Tbe safest mode in doubtful cases is, not to form this appendage

till after tbe principal floor is laid, and then to determine the detaUs of tbe ten-ace

by trial and correction.

1561. Narrow terraces are entirely occupied as promenades, and may be either gravelled

or paved ; and different levels, when they exist, connected by inclined planes or

flights of steps. Where tbe breadth is more tban is requisite for walks, the borders may

be kept in turf with groups or marginal strips of flowers and low shrubs. In some cases,

the terrace-walls may be so extended as to enclose ground sufficient for a level plot to

be used as a bowling-green or a flower-garden. Tbese ai-e generally connected with one

of tbe living-rooms, or the conservatory,

and to tbe latter is frequently

joined an ariaiy and tlie entire range

of botanic stoves. Or, the aviai-y may

be made an elegant detached building,

so placed as to group witb the bouse

and other surrounding objects. A

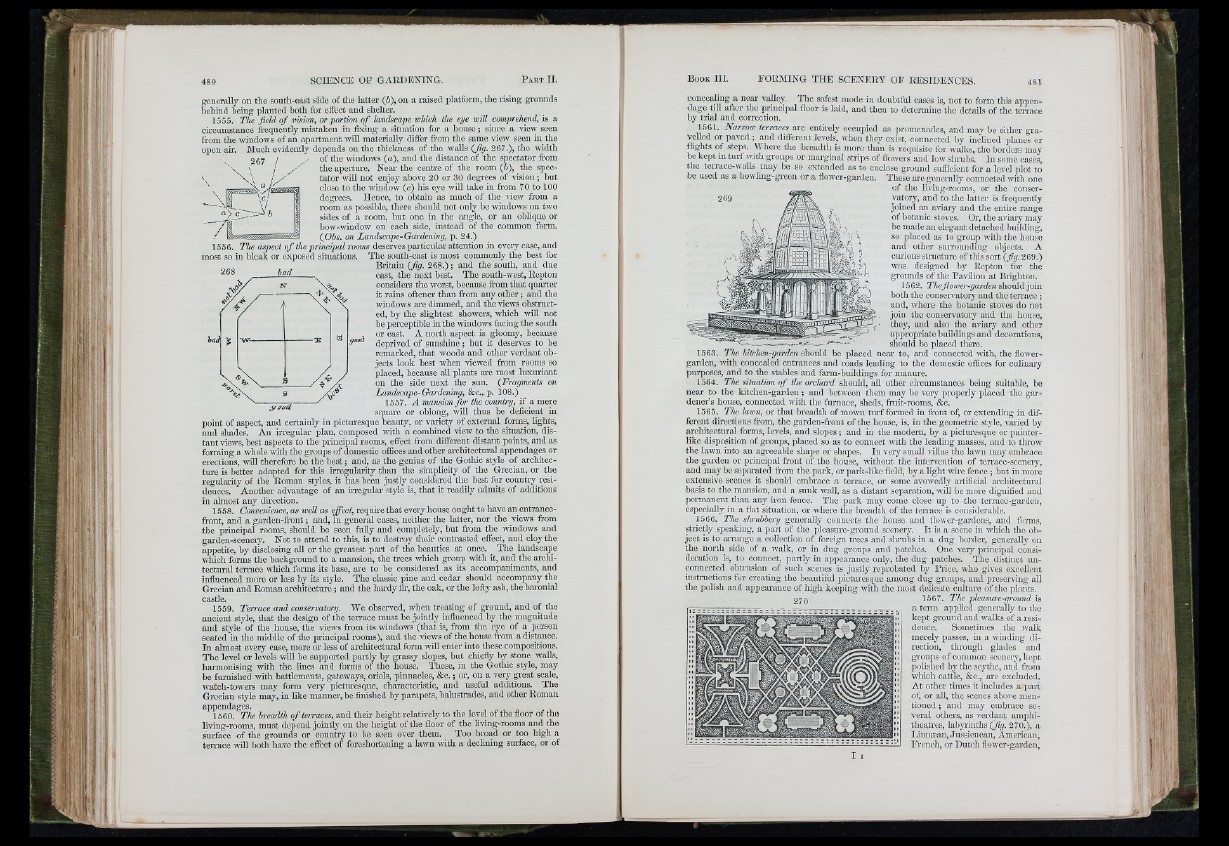

curious sti-ucture of this sort (Jig.269.')

was. designed by Repton for the

grounds of the Pavilion at Brighton.

1562. Thejlower-garden should join

botb the conservatory and the terrace ;

and, where the botanic stoves do not

join the conservatoi-y and tbe house,

they, and also tbe aviai-y and other

appropriate buildings and decorations,

should be placed there.

1563. The Jiitchen-garden sh.o\\\A be placed neai- to, and connected witb, tbe flower-

garden, with concealed entrances and roads leading to tbe domestic offices for culinary

purposes, and to the stables and farm-buildings for manure.

1564. The situation o f die orchard should, all other circumstances being suitable, be

near to the kitchen-garden ; and between them may be vei-y properly placed the gardener’s

bouse, connected with tbe fui-nace, sheds, fmit-rooms, &c.

1565. The lawn, or that breadth of mown tu rf formed in front of, or extending in different

directions fi-om, the garden-front of tbe house, is, in the geometric style, varied by

architectural forms, levels, and slopes; and in tbe modem, by a picturesque or painter-

like disposition of groups, placed so as to connect witb tbe leading masses, and to throw

the lawn into an agreeable shape or shapes. In very small villas the lawn may embrace

tbe garden or principal front of the house, without the intervention of terrace-scenery,

and may be separated from the park, or park-like field, by a light wire fence ; but in more

extensive scenes it should embrace a terrace, or some avowedly artificial architectural

basis to tbe mansion, and a sunk wall, as a distant separation, will be more dignified and

permanent tban any iron fence. Tbe park may come close np to tlie tcrrace-gai’deu,

especially in a flat situation, or where the breadth of tbe ten-ace is considerable.

1566. The shrubbery gcneraliy connects the house aud flower-gardens, and fonns,

strictly speaking, a part of tbe pleasure-ground scenery. I t is a scene iu wliich the object

is to an-angc a collection of foreign trees and shrubs in a dug border, generally on

the north side of a walk, or in dug groups and patches. One very principal consideration

is, to connect, partly in appearance only, tbe dug patches. Tbe distinct unconnected

obtrusion of such scenes is justly reprobated by Price, who gives excellent

instractions for creating the beautiful picturesque among dug groups, and preserving all

tbe polish and appcai-ance of high keeping with the most delicate culture of tbe plants.

1567. The pleasure-ground is

a term applied generally to tbe

kept ground and walks of a residence.

Sometimes the walk

merely passes, in a winding direction,

tbrough glades and

gi-oups of common scenery, kept

polished by the scythe, and from

which cattle, &c., ai-e excluded.

A t other times it includes a part

of, or aU, tbe scenes aboi-e mentioned

; and may embrace scr

veral others, as verdant ampbi-

tbeatrcs, labyrinths (fig. 270.), a

Linuican, Jussieuean, American,

Fi-cnch, or Dutch flower-gai-dcn,

270