V '.- l »

! • -Mi

•i!

„ 1 ?

/ / ¡ • r é

i r é

ré"? '!/

ré'ii'jiréré

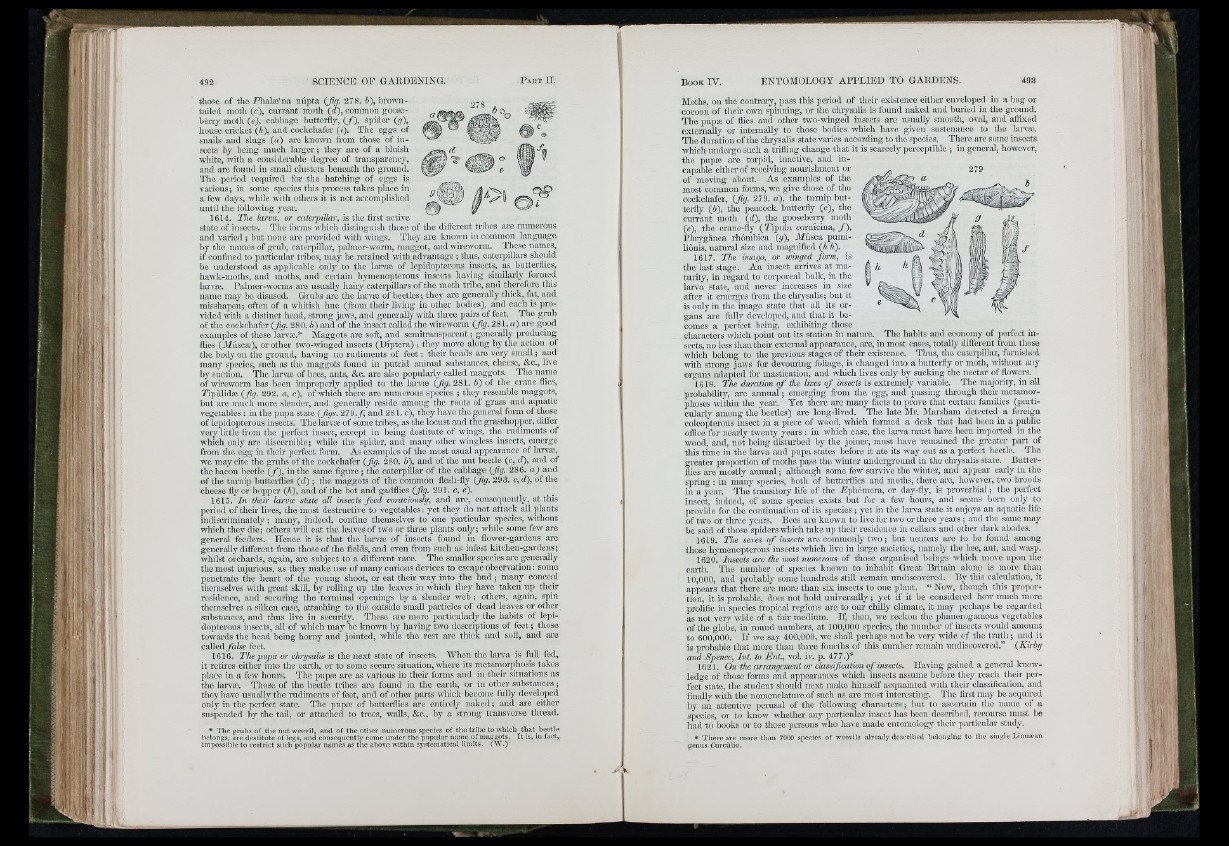

those of the Phaloe'na niipta (Jîg. 278. ¿»), broAvn-

tailecl motil (c), currant moth (¿ ), common gooscb

en y moth (e), cabbage butterfly, ( / ) , spider (g),

house cricket (/¿), and cockchafer (/). Tlic eggs of

snails and slugs (a ) arc knoAvn from those of insects

by being much la rg er; they are of a bluish

white, Avith a considerable degree of transparency,

and are found in small clusters beneath the ground.

The period required for the hatching of eggs is

various; in some species this process takes place in

a fcAv days, Avhile Avitli others it is not accomphslicd

until the folloAving year.

1614. The larva, or caterpillar, is the first active

state of insects. The forms Avhich distinguish those of the different tribes are numerous

and varied ; but none are provided Avith Avings. They ai*e knoAvn in common language

by the names of grub, caterpillar, palmer-Avorm, maggot, and AvircAvorm. Tliese names,

if confined to particular tribes, may be retained with advantage ; thus, caterpillars sliould

be understood as applicable only to the laiwæ of Icpidopterous insects, as butterflies,

haAvk-moths, aud moths, and certain hymenopterous insects liaAung similarly formed

larvæ. Palracr-Avorms are usually hairy caterpillai’s of the moth tribe, and therefore this

name may bo disused. Grubs are the lai-A^æ of beetles; they are generally thick, fat, and

misshapen; often of a Avliitish hue (from their living in other bodies), and each is provided

Avith a distinct head, strong jaAvs, and generally with tlii’ec pairs of feet. Tlie grub

of the cockchafer (fig. 280. b) and of the insect called the Avircworm {fig. 281. a) are good

examples of these larvæ.* Maggots are soft, and seraitranspiu-cnt ; generally producing

flics (iUùscæ), or other tAvo-Avingcd insects (Díptera) ; they move along b y th e action of

the body on the ground, having no mdiments of feet : their heads are very small ; and

many species, such as the maggots found in putrid animal substances, cheese, &c., live

by suction. The lai*væ of bees, ants, &c. arc also popularly called maggots. The name

of AvircAvorm has been improperly applied to the larvæ {fig. 281. 6) of the crane flies,

Tipùlidæ {fig. 292. a, c), of Avhich there are numerous species ; they resemble maggots,

but are much more slender, and generally reside among the roots of gvass and aquatic

vegetables ; in the pupa state {figs. 219. f , and 281. c), they have the general form of tliose

of lepidopterous insects. The lai-A'oe of some tribes, as the locust and the grasshopper, differ

very little from the perfect insect, except in being destitute of Avings, the rudiments of

which only arc discernible ; Avhüe the spider, aud many other Avinglcss insects, emerge

from tho egg in their perfect form. A s examples of the most usual appearance of larvæ,

we may cite the grubs of the cockchafer {fig. 280. b), and of the nut beetle (c, d), and of

the bacon beetle ( / ) , in the same figure ; the caterpülai- of the cabbage {fig. 286. a ) aud

of the turnip butterflies {d) ; the maggots of the common flesh-fly (Jig. 293. c, d), of the

cheese fly or hopper (A), and of the bot and gadflies {fig. 291. c, é).

1615. In their larvæ state all insects feed voi-aciously, and ai'e, consequently, at this

period of their lives, the most destmctiAx to vegetables: yet they do not attack all plants

indiscriminately ; many, indeed, confine themselves to one pai-ticular species, without

which they die; others wiU eat the leaves of two or thi-ce plants only; Avhile some few are

general feeders. Hence it is that the larvæ of insects found in floAver-gardens are

generally different from those of the fields, and even from such as infest kitchen-gardens;

whilst orchards, again, are subject to a different race. The smaller species arc generally

the most injuiious, as they make use of many curious devices to escape observation : some

penetrate the heai-t of the young shoot, or eat thefr way into the bud ; many conceal

themselves with great skill, by roiling up the leaves in which they have taken up their

residence, and seeming the terminal openings by a slender Aveb j others, again, spin

themselves a sUken case, attaching to the outside small particles of dead leaves or other

substances, and thus live in security. These are more particularly the habits of Icpidopterous

insects^ all of which may be knoAvn by having two descriptions of feet ; those

toAvards the head being horny and jointed, while the rest are thick and soft, and are

called false feet.

1616. The pupa or chrysalis is the next state of insects. When the laiwa is full fed,

it retires either into the earth, or to some secure situation, Avhere its metamorphosis takes

place in-a feiv hours. The pupæ are as various in their forms and in thefr situations as

the larvæ. Those of the beetle tribes are found in tlie eai'th, or in other substances ;

they lia,VO usually the rudiments of feet, and of other parts which become fully developed

only in the perfect state. The pupæ of butterflies are entfrely naked ; and are either

suspended by the tail, or attached to trees. Avails, &c., by a strong transverse thread.

* The grubs of th e nut weevil, and of the other numerous species of th e tribe to which that beetle

belongs, are destitute of legs, and consequently come under the popular name of maggots. It is, m fact,

impossible to restrict such popular names as the above within systematical limits. (W.)

Moths, on the contraiy, pass this period of thefr existence either enveloped in a bag or

cocoon of tlieir OAvn spinning, or the clirysalis is found naked and buried in the ground.

The pupæ of flies and other two-winged insects are usually smooth, oval, aud affixed

externally or internally to those bodies which have given sustenance to the laiwæ.

The duration of the chrysalis state varies according to the species. There are some insects

Avhich undergo such a trifling chango that it is scarcely perceptible ; in general, however,

the pupæ ai'e torpid, inactive, and incapable

either of receiving nom-ishmcnt or ^ 279

of moving about. As examples of the

most common forms, we give those of the

cockchafer, (fig. 219. d), the turnip butterfly

(Ô), the peacock buttei-fly (c), the

currant moth (d), the gooseberry moth

(e), the crane-fly (Típ u la cornicina, / ) ,

Pln-ygaiiea rhombica {g), J fú sc a punii-

lionis, natural size and magnified (A A).

1617. The imago, or winged form, is

the last stage. An insect arrives at maturity,

in regard to coi-poreal bulk, in the

larva state, and never increases in size

after it emerges from the chrysalis; but it

is only in the imago state that all its organs

ai-e fully developed, and that it becomes

a perfect being, exliibiting those

c h a r a c te r s Avhich p o in t o u t its s ta tio n in n a tu r e . T h e h a b its a n d e c o n om y o f p e r fe c t i n se

c ts , n o less th a n th c i r e x t e r n a l a p p e ax a n co , a r e , in m o s t ca se s, to ta lly d iffé re n t from th o s e

Avhich b e lo n g to t h e p re v io u s s ta g e s o f th e i r e x is te n c e . T h u s , th e c a te rp illa i-, fu rn is h e d

Avith s tro n g jaAvs fo r d e v o iu -in g fo lia g e , is c h a n g e d in to a buttei-fly o r m o th , Avithout a n y

o rg a n s a d a p t e d fo r m a s tic a tio n , a n d w h ic h liv e s o n ly b y s u c k in g th e n cc tai- o f floAvers.

1618. The duration o f die lives o f insects is extremely vai'iablc. The majority, in aU

probability, are annua l; emerging from the egg, and passing through their metamorphoses

within the year. Yet there are many facts to prove that certain families (particularly

among the beetles) are long-lived. The late Mi'. Marsham detected a foreign

coleopterous insect in a piece of wood, Avhich formed a desk that had been in a public

office for nearly tAventy years : in which case, the lai'va must have been imported iu the

wood, ancl, not being disturbed by the joiner, must have remained the greater part of

this time in the larva and pupa states before it ate its way out as a perfect beetle. The

greater proportion of moths pass the winter underground in the chrysalis state. Butterflies

are mostly annual ; although some fcAv survive the Avinter, and appeal- early in the

spring : in many species, hoth of butterflies and moths, there arc, however, tAvo broods

in a year. The transitory life of the ièphémcra, or day-fly, is proverbial ; the perfect

insect, indeed, of some species exists but for a few houi-s, and seems born only to

provide for the continuation of its species ; yet in the lai-Ara state it enjoys an aquatic life

of two or thi-ee years. Bees are known to live for tAvo or three years ; and the same may

be said of those spiders which take up thefr residence in cellars and other dark abodes.

1619. The sexes o f insects a r c c om m o n ly tw o ; b u t n e u te r s a r c to be fo u n d am o n g

th o s e h ym e n o p te ro u s in s e c ts Avhich liv e in l a r g e so c ie tie s, n am e ly th e b ee , ant, and w a sp .

1620. Insects arc the most numerous of those organised beings which move upon the

earth. The number of species known to inhabit Great Britain alone is more than

10,000, and probably some hundreds still remain undiscovered. By this calculation, it

appears that there arc more than six insects to one plant. “ Noav, though this proportion,

it is probable, does not hold universally ; yet if it be considered hoAv much more

prolific in species tropical regions ai-e to our chilly climate, it may perhaps be regarded

as not very wide of a fair medium. If, then, we reckon the phanerogamous vegetables

o fth e globe, in round numbers, at 100,000 species, the number of insects Avould amount

to 600,000. I f AVC say 400,000, we shall perhaps not be very Avidc cf the truth ; and it

is probable that more than tlu-ce fourths of this number remain undiscovered.” {Kirby

and Spence, Int. to E n t , vol. iv. p. 477.)*

1621. On the arrangement or classification o f insects. H a v in g g a in e d a g e n e r a l k n ow le

d g e o f th o s e fo rm s a n d a p p e a ra n c e s w liic h in s e c ts a s sum e b e fo re th e y re a c h th e i r p e r fe

c t s ta te , th e s tu d e n t s h o u ld n e x t m a k e h im s e lf a c q u a in te d w i th th c i r cla ss ific a tio n , a n d

fin a lly Avith th e n om e n c la tu r e o f su c h a s ai-e m o s t in te r e s tin g . T h e firs t m a y b e a c q u ire d

b y a n a t te n tiv e p e r u s a l o f th e fo llow in g c h a r a c te r s ; b u t to a s c e r ta in th e n am e o f a

sp e c ie s , o r to k n ow Avhether a n y p a r ti c u la r in s e c t h a s b e e n d e s c rib e d , re c o u rs e m u s t b e

h a d t o b o o k s o r to th o s e p e r s o n s Avho h a v e m a d e e n tom o lo g y th c i r p a i-tic u la r s tu d y .

* Theve are more than 7000 species of weevils already described belonging to the single Linnæan

genus Curcùlio.

:• 'J :