albin-num or soft wood is not left for the ascent of the sap, and the shoot dies. In delicate

sorts, it is not sufficient to cut a notch merely, because in that case the descending

sap, instead of throwing out granulated matter in the upper side of the wound, would

descend by the entire side of tlie shoot ; therefore, besides a notch formed by cutting out

a portion of baik and wood, the notched side is slit up at least one inch, scpai-ating it by

a bit of twig, or small splinter of stone or potsherd.

2424. M a n ip u la tio n . Shoots, when layered, ai-e often cut and mangled at random, or

buried sufficiently or so deep in the soil that they throw out but few roots ; or not placed

upright, hy which they make unsightly plants. In order to give some sort of principle

to go upon, it should be remembered, that tlic use of the notch is to prevent the heel, or

part intended to throw out granulons matter, from being braised, which it generally is

hy the common practice of performing this operation hy one cut sloping upwards ; and

that the use of the slit is to render it more difficult for the descending sap to return from

the extremity of the heel. In conformity with this idea, Knight recommends taking up

the shoot after it has grown some time, and cutting off a ring of bark below the notch

and slit, so as completely to hinder the retura of the sap, and thereby force the shoot to

employ it in forming roots. (H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. i. p. 256.) In burying an entire branch

or shoot, with a view to induce shoots to rise from every bud, notches alone are sufficient,

without either slitting or ringing. The use of the splinter of wood, or hit of tile or potsherd,

is pai’tly to prevent the union of the parts when the bent position of the shoot is

not sufficient for that purpose ; and partly, and in some cases principally, to act as a

stimulus like tlie bottom and sides of pots. On what principle it acts as a stimulus has

not, we think, been yet determined ; but, its effects have long been very well known to

gardeners. In all cases the layer must he held firmly in its place by hooked pegs. The

operation of layering is performed on herbaceous plants, as well as trees ; and the part to

become the future plant is covered with soil about a third of its length.

2425. L a y e rin g by tw isting , ring ing , piercing , and w irin g the shoot intended for tho

future plant, is also occasionally practised.

2426. P ie rc in g is performed with an awl, nail, or penknife, thrast through two or

three times in opposite directions at a joint ; from which wounds first gi-anulated matter

oozes, and finally fibres are emitted.

2427. R in g in g is cuttmg off a small ring of bark, by which, the return of the sap being

prevented, it is, as it were, compelled to form roots. Caro must be taken, however, that

the ring does not penetrate fai* into tlie wood, otherwise the sap will be prevented from

ascending in the first instance, and the shoot killed.

2428. W irin g is performed by twisting a piece of wire round the shoot at a joint, and

pricking it at the same time witli an awl on both sides of the wire. It is evident that

all these methods depend on the same general principle ; viz. that of permitting the

ascent of the sap through the wood, and checking its descent by cutting off, or closing,

the vessels of tlie bark.

2429. L a y e rs which are d iffic u lt to strike may be accelerated by ringing. Ringing is

an excellent method for making layers of hard-wooded plants strike root with greater

certainty, and in a smaller space of time than is attained in any other way. The accumulated

vegetable matter in the callus, which is formed on the upper edge of the ring,

when brought into contact with the soil, or any material calculated to excite vegetation,

readily breaks into fibres and roots. (H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. iv. p. 558.)

2430. I n layering trees in the open garden, whatever mode be adopted, the ground

round each plant intended for laying must be dug for the reception of the layers ; then,

making excavations in the eaith, lay down all the shoots or branches properly situated

for this purpose, pegging each down with a peg or hooked stick, laying also all the

proper young shoots on each branch or main shoot, fixing each layer fi-om about 3 or

4 to 6 inches deep, according as they admit, and moulding them in at that depth, leaving

the tops of every layer out of the ground, from about 2 or 3 to 5 or 6 inches, according

to their length, though some shorten their tops down to one or two eyes. Observe

also to raise the top of each layer somewhat upright, especially tongue or slit layers, in

order to keep the slit open. As the layering is completed, level in all the mould finely

and equally in every part close about every layer, leaving an even, smooth surface,

presenting only the tops of each layer in the circumference of a circle, and the stems or

stools in the centre. Sometimes the branches of trees are so inflexible as not to be easily

brouglit down for laying ; in which case they must be plashed, making the gash or cut

on the upper side ; and when they are grown too large for plashing, or that the nature

of the wood wül not bear that operation, the trees may be thrown on their sides, by

opening the earth about their roots, and loosening or cutting all those on one side, that

tlie plant may be brought to the ground to admit of laying the branches.

2431. L a y e rin g p la n ts in pots. When layers are to he made from greenhouse shrubs,

or other p la n ts in pots, the operation should generally be performed either in their own

pots, or in others placed near that of the stool to receive the layer.

2432. G e ne ral treatment. After laying in either of the above methods, there is no

particular culture requisite, except that of keeping the earth as much as possible

of uniform moisture, especially in pots ; and watering the layers in the open air in dry

weather.

2433. M anag em ent o f stools. When the layers are rooted, which will generally he the

case hy the autumn after the operation is performed, they are ah cleared from the stools

or main plants, and the head of each stool, if to he continued for furnishing layers,

should be dressed; cutting off all decayed and scraggy parts, and digging the ground

round each plant. Some iresh rich mould should also he worked in, in order to encourage

the production of the annual supply of shoots for layering.

2434. Chinese laying . The Chinese method of propagating trees, hy first ringing, or

nearly so, a shoot, and then covering the ringed part with a ball of clay and earth

covered with moss or straw, is obviously on the same general principle as layering; and

is better effected in this country by drawing the shoot through a hole in a pot; ringing

it to the extent of three fourths of its circumference, near the bottom or side of the pot,

and then, the pot being supported in a proper position, and filled with eai'th, it may he

watered in the usual way. Some plants difficult to strike, and for which proper stocks

for inarching are not conveniently procvu-ed, are thus pro]5agated in the nursery hothouses.

2435. R em oval o f the rooted layer o r p la n tle t. Though layers of trees completed early

in spring, and of lierbaceous plants after the season of tlicir flowering, are g en e ra lly to

remove from the parent plant the end of the succeeding autumn; yet many sorts of

American trees require two years to complete their roots. Ou the other hand, some sorts

of roses and deciduous shrubs, if their present year’s wood be laid down when about half

grown, or about the middle of August, will produce roots, and be fit to sepai-ate, the

succeeding autumn.

S u b se c t. 3. P ro p ag atio n hy In a rc h in g .

2436. In a rc h in g . This is probably the most ancient of all kinds of grafting, and,

indeed, the natural inosculation of trees in forests probably gave mankind the idea

of practising grafting as an art of ciiltui-e. In a state of nature, two branches, rubbed

together by the wind become bruised, and if they aftenvards remain quietly resting on

each other during the groiving season, their inner barks easily unite, and inosculation or

natural inarching takes place. It is evident that in a state of natm-e these examples

cannot he of very frequent occiin-ence, as they require certain conditions which can only

happen under peculiai* circumstances; but wlien these circumstances and thcir effects had

been once observed, nothing could be more easy than for man to imitate them exactly.

Thus, all that is necessary to perform the operation of inarching is to deprive the two

branches which are to be united of theii* outer bark, and to unite the liber of the two

as exactly as possible, afterwards binding the two branches together in such a manner

as to prevent them from moving till they become united. As tlie art continued to be

practised, greater neatness would be attempted by cutting the two branches so that they

might unite exactly with each other without fonning any knot or excrescence, and, in

fact, to look as though the stock and scion were only one tree. There are several

different modes of perfoi-ming the operation, but they may be all reduced to four. The

different modes of inarcliing are thus enumerated in Du Brcuil’s C ours E 'lem e n ta ire

d 'A rb o ric u ltu re (1846).

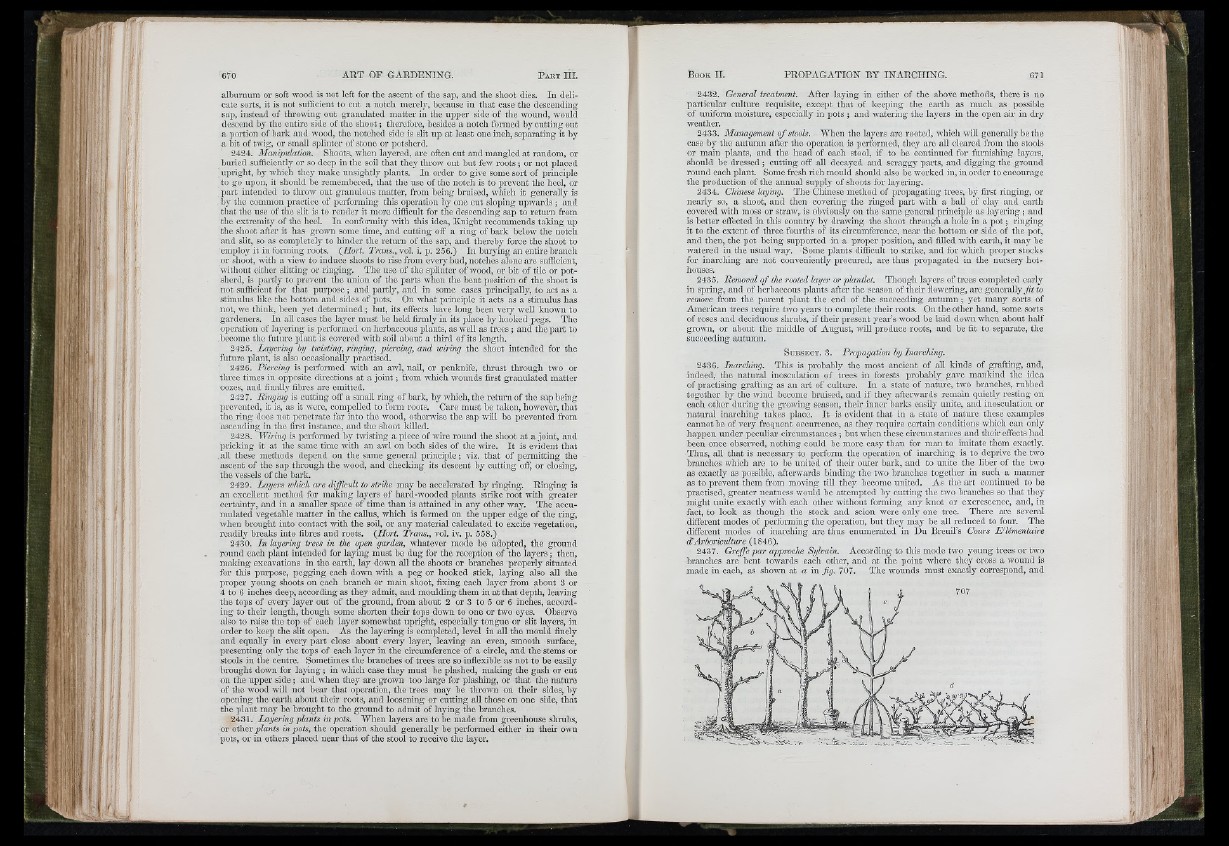

2437. G re ffe p a r approche S y lv a in . According to this mode two young trees or two

branches are bent towards each other, and at the point where they cross a wound is

made in each, as shown at a in fig . 707. Tho wounds must exactly correspond, and

’’ k|