r>

bery, pleasure-ground, &c. (when there are plaut-stoves and collections of florists’ flowers,

these departments sliould be divided), and one to the woods and plantations, unless there

is a reguhir forester dfrectly under tho control of the master. To each of these foremen a

limited number of permanent men should be assigned, and, when occasion requfres, assistance

should be allowed them, either by common labourei*s or women, or hy a tempora

iy transfer of hands from any of the other departments from which they can be

spai-ed.

1670. Economical arrangements. The next thing is to fix on the hours of labour and

of rest, the amount of wages, and regulations as to lodging, &c. The hours of labour

ought to be at least one hour per day less than those for field labourers (who requfre

compai-atively no mind), in order to allow time for studying the science of the art to be

practised. The amount of fines should also be fixed on at the same time : as for absence

a t the hoiu-s of going to labour; for defects in the performance of duty of various sorts,

as putting by a tool without cleaning it, being found without a knife or an apron, or not

knowing the name of a plant, &c. A set of maxims and rules of conduct should bo

di-awn up by the master, and printed, with the amount of fine specified at the end of each

rule. The fines levied may either be applied to some general pui-pose, or returned by

equal distribution quarterly.

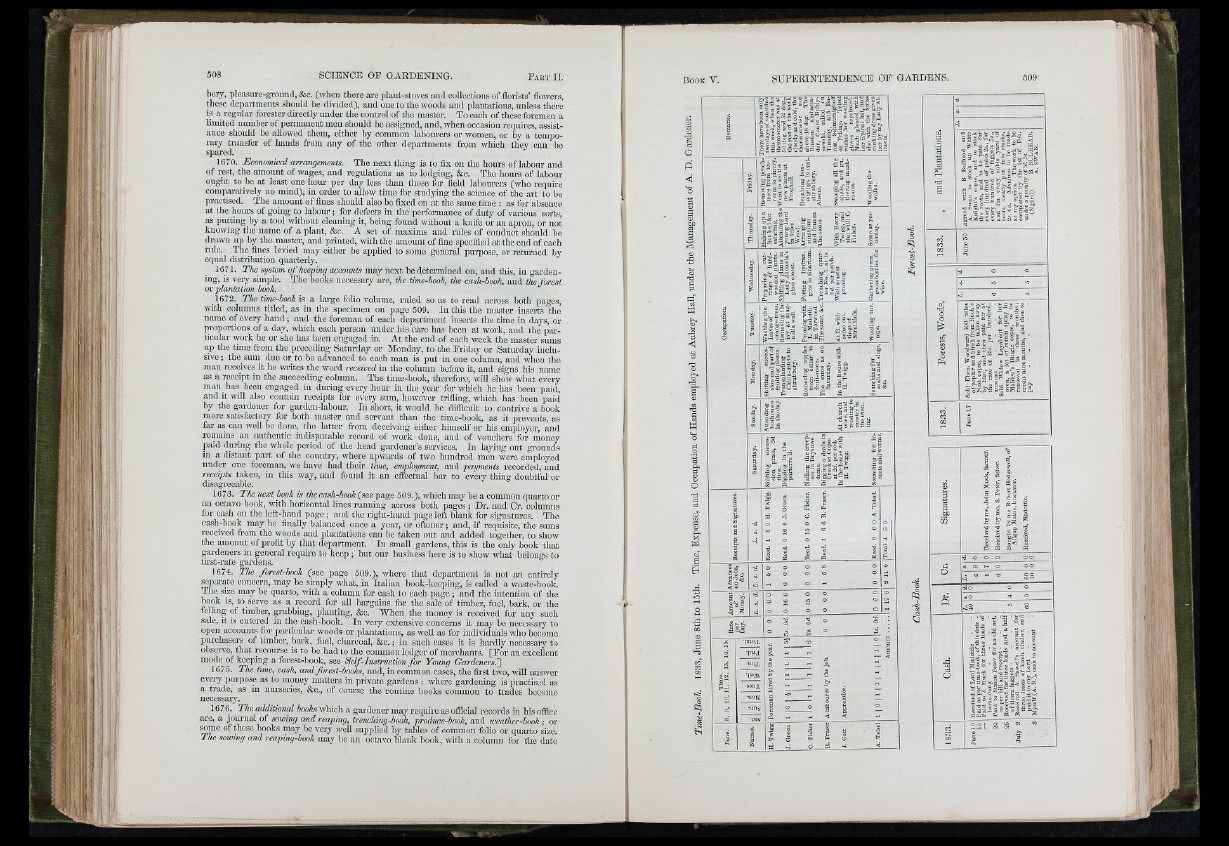

1671. The system o f keeping accounts may next be determined on, and this, in gardening,

is very simple. The books necessaiy are, the time-book, the cash-book, aud the forest

or plantation book.

1672. The time-book is a large folio volume, ruled so as to read across both pages,

with columns titled, as in the specimen on page 509. lu this the master inserts the

name of every hand ; and the foreman of each department inserts the time in days, or

pi-oportions of a day, which each person under his care has been at work, and the particular

work he or she has been engaged in. A t the end of each week the master sums

up the time from the preceding Saturday or Monday, to the Friday or Saturday inclusive

; the sum due or to be advanced to each man is put in one column, and when the

man receives it he wi-ites the word received in the column before it, and signs his name

as a receipt in the succeeding column. The time-book, therefore, will show what every

man has been engaged in during every hour in the yeai- for which he has been paid,

and It will also contain receipts for every sum, however trifling, which has been paid

by the gardener for gardon-laboui-. In short, it would be difficult to contrive a book

more satisfactory for both master and servant than the time-book, as it prevents, as

far as can well be done, the latter from deceiving cither himself or his employer, and

remains an authentic indisputable record of work done, and of vouchers for money

paid diiring tho wholc period of the head gai-dener’s services. In laying out grounds

in a distant part of the country, where upwards of two hundred men were employed

under one foreman, we have had thoir time, employment, and payments recorded, and

receipts taken, in this way, and found it an effectual bai- to every thing doubtful or

disagi-eeablc.

1673. Thenext book is /Aeccw/t-Aoo/e (seepage 509.), which may be a common quarto or

an octavo book, with horizontal lines running across both p ag e s; Dr. and Cr. columns

for cash on the left-hand p a g e ; and the right-hand page left blank for signatui-es. The

cash-book may be finally balanced once a year, or oftener; and, if requisite, the sums

received from the woods and plantations can be taken out and added together, to show

the amount of profit by that depaitraent. In small gardens, this is the only hook that

gardeners in general requii-e to keep ; but our business here is to show what belongs to

first-rate gardens.

1674. The forest-book (see page 509.), where that department is not an entirely

sep.ai-atc concern, may be simply what, in Italian book-keeping, is called a wastc-book.

The size may bo quarto, with a column for cash to each p a g e ; and the intention of the

book is, to serve as a record for all bargains for the sale of timber, fuel, hark, or the

felling of timber, grubbing, planting, &c. Wlien the money is received for any such

sale, it is entered in the cash-book. In very extensive concerns it may be neccssai-y to

open accounts for particular woods or plantations, as well as for individuals who become

purchasers of timber, bark, fuel, charcoal, &c.; in such cases it is hardly necessai-y to

observe, that recourse is to be had to the common ledger of merchants. [F o r an excellent

mode of keeping a forest-book, see Self-Instruction fo r Young Gardeners."]

1675. The time, cash, and forest-books, and, in common cases, the first two, will answcr

every purpose as to money matters in private gardens : where gardening is practised as

a trade, as in nurseries, &c., of course the routine books common to trades become

necessary.

1676. The additional AooAs which a gardener may requfre as official records in his office

are, a journal of sowing and reaping, trenching-book, produce-book, and weather-book ; or

some of these books may be very weU supplied by tables of common folio or quarto size.

The sowing and reaping-book may be an octavo blank book, with a column for the date

a l ’g-o'a isäiiiiilisiiiEiyniis

kI

i l l I f ^ ig 5 ^

r y .

i ' ! | | |

n i l 1.1 : “ i s „

I s l i

ill p s r i A iS - §

i 'S I 1

1

Ä 1 ii

M i l l

1 I I |l i I I If 1

o O O o o

Ö

.5 o> C- O o o

.q ^ g s

• eo o o

S

r iO o

. 4S ” 8

A

' i i ' I ' l ' ? ! ?

i f ' i t i i i J

ill

CCOO

00 I 1

t a l i