Ita I

i Li

calls the old method, the general shape of the

plant when pruned and trained being like

th a t of a trained peach ; th e second he agrees

with Abercrombie in calling spur-pruning,

or spurring in ; and the third he calls the

long or new method {fig. 770.) ; “ though,”

he adds, “ I understand by books {Switxer,

and The Retired Gardener,) that it was in

practice nearly one hundred years ago, and

I saw it in practice forty years since.” It

is singular that this old inethod of M‘Phail

should have been described and figured by

a German horticulturist, as a new and “ experimentally

proved superior method of vine

culture Versuch einer durch Erfahrung

erprubten methode den Weinbau zu verbessern,

von J . C. Kecht, Berlin, %vo. 1813.

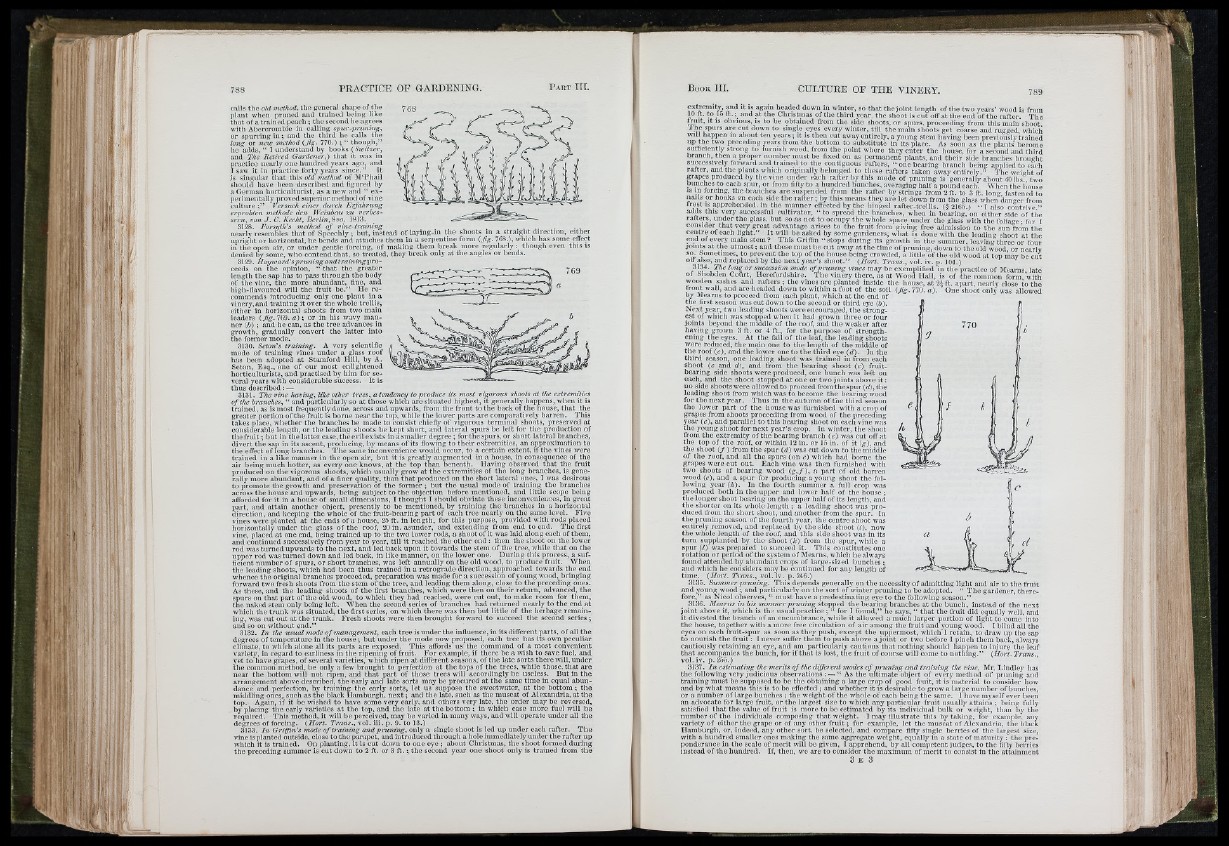

3128. Forsyth's method of vine-training _ . a • w ,. a- -au

nearly resembles that of ^Speechly ; but, instead oflaying-in th e shoots m a straight direction, either

upright or horizontal, he bends and attaches them in a serpentine form {fig. 7G8.), which has some eliect

in the open air, or under gentle forcing, of making them break more re g u la rly : though even this is

denied by some, who contend that, so treated, they break only a t th e angles or bends.

3129. flayward'spruningandtrainingx>ro-

ceeds on th e opinion, “ th a t th e greater

length th e sap has to pass through th e body

of the vine, the more abundant, fine, and

high-flavoured will th e fruit b e.” He recommends

introducing only one plant in a

vinery.and training it over the whole treUis,

either in horizontal shoots from two main

leaders 7G9. a ) ; or in his wavy mann

er (J) ; and he can, as th e tree advances in

growth, gradually convert th e latte r into

the former mode.

3130. Seton's training. A very scientific

mode of training vines under a glass roof

has been adopted a t Stamford Hill, by A.

Seton, Esq., one of our most enlightened

horticulturists, and practised by him for several

years with considerable success. It is

thus described: —

3131. The vine

line having, like other trees, a tendency to produce its most vigorous shoots at the extremities

ofthe branches, “ and particularly so at those which are situated highest, it generally happens, when it is

trained, as is most fi

frequently done, across and upwards, from th e front to the back of the house, that the

greater portion of the fruit is borne near the top, while the lower parts are comparatively barren. This

takes place, whether the branches be made to consist chiefly of vigorous terminal shoots, preserved a t

considerable length, or the leading shoots be kept short, and lateral spurs be left for the production of

the f r u it; but in the latter case, theevil exists in a smaller degree; for the spurs, or short lateral branches,

divert the sap in its ascent, producing, by m eans of its flowing to thoir extremities, an approximation to

the effect of long branches. T h e same inconvenience would occur, to a certain extent, if the vines were

trained in a like manner in th e open air, but it is greatly augmented in a house, in consequence of the

air being much hotter, as every one knows, a t the top than beneath. Having observed th at th e fruit

produced on th e vigorous shoots, which usually grow a t th e extremities of th e long branches, is generally

more abundant, and of a finer quality, than that produced on the short lateral ones, I was desirous

to promote the growth and preservation of the former ; but the usual mode of training th e branches

across the house and upwards, being subject to th e objection before mentioned, and little scope being

afforded for it in a house of small dimensions, I thought I should obviate these inconveniences, fn great

part, and attain another object, presently to be mentioned, by training th e branches in a horizontal

direction, and keeping the whole of th e fruit-bearing part of each tree nearly on the same level. Five

vines were planted a t th e ends of a house, 2h ft. in length, for this purpose, provided with rods placed

horizontally under th e glass o f th e roof, 20 in. asunder, and extending from end to end. The first

vine, placed a t one end, being trained up to the two lower rods, a shoot of it was laid along each of them,

and continued successively from year to year, till it reached th e other end : then the shoot on th e lower

rod was turned upwards to the next, and led back upon it towards the stem of the tree, while th a t on the

upper rod was turned down and led back, in like manner, on the lower one. During this process, a sufficient

number of spurs, or short branches, was left annually on the old wood, to produce fruit. When

the leading shoots, which had been thus trained in a retrograde direction, approached towards the end

whence the original branches proceeded, preparation was made for a succession ofyoungwood, bringing

forward two fresh shoots from the stem of the tree, and leading them along, close to the preceding ones.

As these, and th e leading shoots of the first branches, which were then on their re turn, advanced, the

spurs on th a t part of the old wood, to which they had reached, were cut out, to make room for them,

the naked stem only being left. When the second series of branches had returned nearly to the end at

which the tru n k was situated, th e first series, on which there was then but little of the herbage remaining,

was cut out a t the tru n k . Fresh shoots were then brought forward to succeed the second series ;

and so on without end.”

3132. I n the usual mode o f management, each tree is under th e infiuence, in its different parts, of alUhe

degrees of temperature in the house ; hut under the mode now proposed, each tree has its own peculiar

climate, to which alone all its parts are exposed. This affords us th e command of a most convenient

variety, in regard to earliness in the ripening of fruit. F or example, if th ere be a wish to save fuel, and

yet to have grapcs, of several varieties, which ripen at different seasons, of the late sorts there will, under

tlie common method, be only a few brought to perfection a t the tops of th e trees, while those, th a t are

near th e bottom will not ripen, and th a t part of those trees will accordingly be useless. But in the

arrangement above described, th e early and late sorts may be procured a t the same time in equal abundance

and perfection, by training the early sorts, let us suppose the sweetwater, a t the bottom ; the

middlmg ones, such as the black Hamburgh, n e x t ; and the late, such as th e muscat of Alexandria, at the

top. Again, if it be wished to have some very early, and others very late, the order may be reversed,

by placing th e early varieties at th e top, and th e late a t th e bottom ; in which case more fuel will be

required. This method, it will be perceived, may be varied in many ways, and will operate under all the

degrees of forcing. {Hort. Trans., vol. iii. p. 9. to 13.)

3133. I n Griffin's mode o f training and pruning, only a single shoot is led up under each rafter. The

vine is planted outside, close to the parapet, and introduced through a hole immediately under the rafter up

which I t is trained. On planting, i t is cut down to one eye ; about Christmas, tho shoot formed during

th e preceding summer is cut down to 2 ft. or 3 f t . ; the second year one shoot only is trained from the

extremity and it is again headed down in winter, so that th cjo ln t length o fth e two years’ wood is from

10 ft. to 1.5 ft. 1 and a t the Christmas of the third year, the shoot is cut off a t the end of the rafter. The

truit, It IS obvious, IS to be obtained from the side shoots, or spurs, proceeding from this main shoot

1 he spurs are cut down to single eyes every winter, till the main shoots get coarse and rugged, which

will happen m about ten y ea rs; it is then cut away entirely, a young stem having been previously trained

up the two preceding years from the bottom to substitute in its place. As soon as the nlants

SUlllCieiltly strong to i"TTiicli IVcm fV,« .TrUr,-„ 4.L. A..__, I dj O..OT j.OT.A.v OT i.ijc j'v iiLA_c i Ai_fc -i iu 1_i_iu_u_B_u , lo i « su c^ u iiu, a u u c n i r a

branch, then a proper number must be fixed on as permanent plants, and th e ir side branches broufiht

successively forward and trained to th e contiguous rafters, “ one bearing branch being applied to each

ra lte r, ami the plants which originally belonged to these rafters taken away entirely.” The weicht of

grapes produced by the vine under each rafter by this mode of pruning is generally about 40!bs two

bunches to each spur, or from fifty to a hundred bunches, averaging half a pound each. 11-11611 the house

IS m forcing, the branches are suspended from the rafter by strings from 2 ft. to 3 ft. long, fastened to

nails or hooks on each side the ra lte r; by this means they are let down from the glass when danger from

frost IS apprehended, ill th e manner effected by th e hinged rafter-trellis. (§ 216.5.) “ I also contrive ”

“ to spread^the b rp c h e s , when in bearing, on either side of the

e ; for 1

centre o-t each light.” It will be asked by some gardeners, what is done with the leading shoot*™ the

end of every mam stem? This Griffin “ stops during its growth in the summer, leaving three or four

joinfo a t the u tm o st; and these must be cut away at th e time of pruning, down to the old wood or nearly

so. Sometimes, to prevent the top of the house being crowded, a little of the old wood at too mav be cut

off also, and replaced by the next year’s shoot.” {Hort. Trans., vol. iv. p. 104.)

3134. The long or succession mode o f pruning vines may be exemplified in the practice of Mearns late

o f Shobden Court, Herefordshire. The vinery there, as a t Wood Hall, is of the common form with

wooden sashes and rafters ; the vmes are planted inside the house, a t 2i ft. apart, nearly close to the

front wall, and are headed down to within a foot of the soii {fig. 770. a). One shoot only was allowed

by Mearns to proceed from each plant, which a t the end of

th e flrst season was cut down to th e second or third eye {b).

Next year, two leading shoots were encouraged, the strongest

of which was stopped when it had grown three or four

joints bey<iiid th e middle of the roof, and the weaker after

haying grown 3 ft. or 4 ft., for the purpose of strength,

ening the eyes. At the fall of the leaf, the leading shoots

were reduced, the main one to the length of th e middle of

th e roof (c), and the lower one to th e third eye {d). In the

third season, one leading shoot was trained in from each

shoot (c and d], and from th e bearing shoot (c) fruit-

bearing side shoots were produced, one bunch was left on

each, and the shoot stopped a t one or two joints above i t :

no side shoots were allowed to proceed from thespur(rf), the

leading shoot from which was to become th e bearing wood

for the next year. Thus in the autumn o fth e third season

tho lower part of th e house was furnished with a crop of

grapes from shoots proceeding from wood of the preceding

year {e), and parallel to this bearing shoot on each vine was

th e young shoot for next year’s crop. In winter, the shoot

from the extremity of the bearing branch (e) was cut oif at

th e top of the roof, or within 12 in. or 1.5 in. of it {g). and

th e shoot { f ) from the spur {d) was cut down to the middle

of the roof, and all th e spurs fyn e) which had borne the

grapes were cut out. Each vine was then furnished with

two shoots of bearing wood { g ,f ) , a part of old barren

wood (e), and a spur for producing a young shoot the following

year {k). In th e fourth summer a full crop was

produced both in the upper and lower half of the house ;

the longer shoot bearing on th e upper half of its length, and

th e shorter on its whole length ; a leading shoot was produced

from the short shoot, and another from the spur. In

th e pruning season of the fourth year, th e centre shoot was

entirely removed, and replaced by the side shoot (0, now

th e whole length of the roof, and this side shoot was in its

tu rn supplanted by th e shoot {k) from the spur, while a

spur _(/) was prepared to succeed it. This constitutes one

rotation or period of the system of Mearns, which he always

found attended by abundant crops of large-sized bunches ;

and which he considers may be continued for any length of

time. {Hort. Trans., v o l.iv . p. 246.)

3135. Sujmncr pruning. This depends generally on the necessity of admitting light and air to th e fruit

and young wood ; and particularly ou the sort of winter pruning to be adopted. “ The gardener, th erefore,”

as Nicol observes, “ must nave a predestinating eye to the following season.”

313G. Mearns in his summer pruning siogpiid the bearing branches at the bunch, instead of the next

jo in t above it, which is th,' usual practice ; “ for I found,” he says, “ that the fruit did equally well, and

it divested the branch of an encumbrance, while it allowed a much larger portion of light to come into

the house, together with a m ore free circulation of air among th e fruit and young wood. I blind all the

eyes on each fruit-spur as soon as they push, except th e uppermost, which I retain, to draw up the sap

to nourish the f r u it : I never suffer them to push above a jo in t or two before I pinch them back, ahvays

cautiously retaining an eye, and am particularly cautious th a t nothing should happen to injure the leaf

th a t accompaniefi th e bunch, for if th a t is lost, the fruit of course will come to nothing.” {Hort'.. .TTrans.,

3137. I n estimating the merits o f tke dffci-ent modes of pruning and training the vine, Mr. Ifindley has

the following very judicious observations : — “ As th e ultimate object of every method of pruning and

training m ust be supposed to be the obtaining a large crop of good fruit, it is material to consider how

and by what means this is to be effected ; and whether it is desirable to grow a large number of bunches,

or a number of large bunches ; the weight of the whole of each being the same. 1 have myself ever been

an advocate for large fruit, or the largest size to which any particular fruit usually attains ; being fully

satisfied tb a t the value of fruit is more to be estimated by its i individual bulk or weight, than by the

the

number of the individuals luais composing comnosine that tnat weight.weient. 1 jm may a v ili illustrate ........................... this by taking,’ ’

for example, any

variety of either the grape o r of any , other fruit ;, for example,^ , let the muscat of Alexandria, the black

, ______________ ______________

Hamburgh, or, indeed, any other sort, be selected, and compare fifty single berries of the largest size,

with a hundred smaller ones making th e same ^ weiogt- ht,, eq. ually in a state of maturit^y : the jireponderance

in the scale of merit will be given, I apprehend, by all competent judges, to the fifty berries

instead of the hundred. If, then, we are to consider the maximum of merit to consist in the attainment

*.i

i' '

viVi