iI. I i

1

ré*

j 1' fr'- I

2110 B ro a d and deep flu e s , agreeably to the Dutch practice, have been

recommended by Stevenson {C a le d . Mem.); that of making J»'-

row and deep, agreeably to the practice in Russia, is recommondod by

Oldacro, gardener to Sir Joseph Banks ; and that of u^ng thin bricks (fig .

614.) with tliiek edges, by J. R. Gowen, Esq. (H o rt. T ra n s ., m.) In Mi.

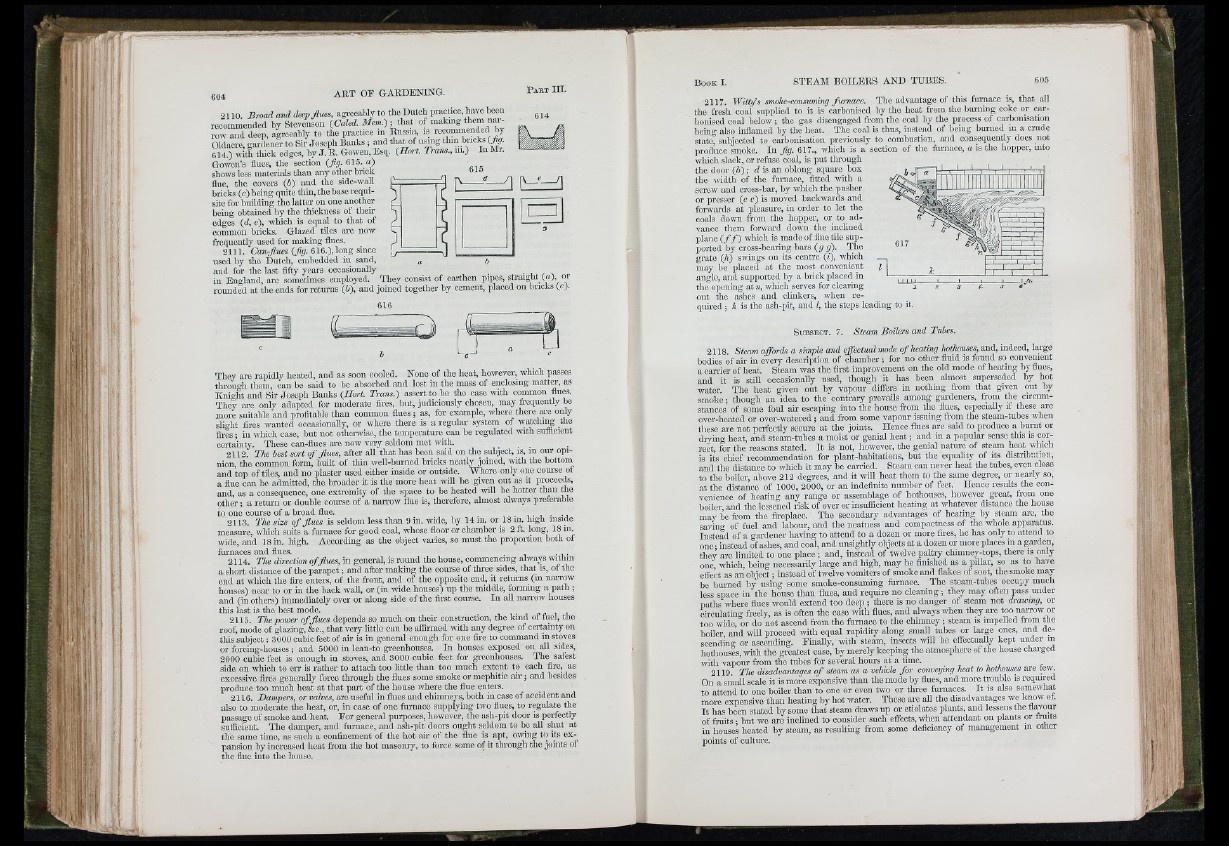

Gowen’s flues, the section (fig . 615. a)

shows less materials than any other brick

flue, the covers (b ) and the sidc-wall

bricks (c) being quite thin, the base requisite

for building the latter on one another

i l

being obtained by the thickness of their

edges (d, e), which is equal to that of

common bricks. Glazed tiles are now

frequently used for making flues.

2111. Can-Jlues (fig . 616.),long since

used by the Dutch, embedded iu sand,

and for the last fifty years occasionally . , , n

in England, are sometimes employed. They consist of earthen pipes, straight (a ), oi

rounded at the ends for returns (b ), and joined together by cement, placed on bricks (c).

They are rapidly heated, and as soon cooled. None of the heat, however, which passes

through them, can be said to be absorbed and lost in the mass of enclosing matter, as

Knight and Sir Joseph Banks (H o rt. T ra n s .) assert to be the case with common flues.

They are only adapted for moderate fires, but, judiciously chosen, may frequently be

more suitable and profitable than commou flues; as, for example, where there arc only

slight fires wanted occasionally, or where there is a regular system of watchi^ the

fires; in which case, but not otherwise, the temperature can be regulated with sufficient

certainty. These can-flues are now very seldom met with.

2112. T h e best sort o f fin e s , after all that has been said on the subject, is, in our opinion,

the common form, huilt of thin well-bm-ned bricks neatly joined, with the bottoni

and top of tiles, and no plaster used either inside or outside. Where only one course of

a flue can be admitted, the broader it is the more heat will he given out as it proceeds,

and, as a consequence, one extremity of the space_ to be heated will be hotter than ffie

other ; a return or double coui'se of a narrow flue is, therefore, almost always preferable

to one course of a broad flue. _ . , . , • -j

2113. T he size o f fin e s is seldom less than 9 in. wide, by 14 in. or 18 in. high mside

measure, which suits a furnace for good coal, whose floor or chamber is 2 ft. long, 18 in.

wide, and 18 in. liigh. According as the object vaiics, so must the proportion both of

furnaces and flues. .

2114. Th e d irection o f flu e s , in general, is round the house, commencing always withm

a short distance of the parapet; and after making the com-se of three sides, that is, of the

end at wliich the fire enters, of the front, and of the opposite end, it rctiu-ns (in narrow

houses) near to or in the back waU, or (in -wide houses) up the middle, fonnmg a path;

and (in others) immediately over or along side of the first com-se. In all narrow houses

this last is the best mode.

2115. T he pow er o f fin e s depends so much on their construction, the kind of fuel, the

roof, mode of glazing, &c., that very little can be affii-med with any degree of certainty on

this subject: 3000 cubic feet of air is in general enough for one fire to command in stoves

or forcing-houscs; and 5000 in lean-to greenhouses. In houses exposed on all sides,

2000 cubic feet is enough in stoves, and 3000 cubic feet for greenhouses. Tlie safest

side on which to err is rather to attach too little than too much extent to each fire, as

excessive fires generally force through the flues some smoke or mephitic air; and besides

produce too much heat at that pait of the house where the flue enfyrs.

2116. D am p ers, or w/aes, are useful in flues and chimneys, both in case of accident and

also to moderate the heat, or, in case of one furnace supplying two flues, to regulate the

f smoke and heat. Eor general purposes, however, the ash-pit door is perfectly

sufficient. The damper, and furnace, and ash-pit doors ought seldom to be all shut at

the same time, as such a confinement of the hot air of the flue is apt, owing to its expansion

by increased heat from tlic hot masonry, to force some of it through the joints of

the flue into the house.

Book I.

2117. W itty ’s smoke-consuming fu rn a c e . The advantage of this furnace is, that ail

the fresh coal supplied to it is carbonised hy the heat fr-om the burning coke or carbonised

coal below ; the gas disengaged from the coal by the process of carbonisation

being also inflamed by the heat. The coal is thus, instead of being burned in a crude

state, subjected to carbonisation previously to combustion, and consequently does not

produce smoke. In fig . 617., which is a section of the fm-nace, a is the hopper, mto

which slack, or reliise coal, is put through

the door (b ) ; d is an oblong square box

the ividth of the furnace, fitted with a

screw and cross-bar, by which the pusher

or presser (c c) is moved backwards and

forwards at pleasure, in order to let the

coals down from the hopper, or to advance

them fonvard down the inclined

plane ( / / ) which is made of fine tile supported

by cross-bearing bars (g g ). The

grate (h ) swings on its centre ( i) , which

may be placed at the most convenient

angle, and supported by a brick placed in

the opening atn, which sei-ves for clearing

out the ashes and clinkers, when required

; k is the ash-pit, and I, the steps leading to it.

SuBSECT. 7. Steam B o ile rs and Tabes.

2118 Steam afford s a simple and effectual mode o f heating hothouses, and, indeed, large

bodies of air in eveiy description of chamber ; for no other fluid is found so convenient

a can-ier of heat. Steam was the first improvement on the old mode of heating by flues,

and it is still occasionally used, though it has been almost superseded by hot

water. The heat given out by vapour differs in nothing from that given out by

smoke ; though an idea to the contrary prevails among gardeners, from the cfrcrnn-

stances of some foul air escaping into the house from the flues, especially if these are

over-heated or over-watered ; and from some vapour issuing from the steam-tubes when

these are not perfectly secure at the joints. Hence flues are said to produce a burnt or

drying heat, and steam-tubes a moist or genial heat ; and in a popular sense this is correct,

for the reasons stated. It is not, however, the genial nature of steam heat which

is its chief recommendation for plant-habitations, but the equality of its distribution,

and the distance to which it may be carried. Steam can never heat the tubes, even close

to the boiler, above 212 degrees, and it will heat them to the same degree, or nearly so,

at the distance of 1000, 2000, or an indefinite number of feet. Hence results the convenience

of heating any range or assemblage of hothouses, however gi-eat, from one

boiler, and the lessened risk of over or insufficient heating at whatever distance the house

may be from the fireplace. The secondary advantages of heating by steam are, the

saving of fuel and labour, and the neatness and compactness of the whole apparatus.

Instead of a gardener having to attend to a dozen or more fires, he has only to attend to

one • instead of ashes, and coal, and unsightly objects at a dozen or more places in a garden,

they are limited to one place ; and, instead of twelve paltry chimney-tops, there is only

one which, being necessarily large and high, may be finished as a pillar, so as to have

effect as an object ; instead of twelve vomiters of smoke and flakes of soot, the smoke may

be bm-ned by using some smoke-consuming furnace. The steam-tubes occupy much

less space in the house than flues, and require no cleaning ; they may often pass nnder

paths where flues would extend too deep ; there is no danger of steam not draw ing , or

circulating freely, as is often the case with flues, and always when they are too narrow or

too wide, or do not ascend from the furnace to the chimney ; steam is impelled from the

boiler and wfil proceed with equal rapidity along small tubes or large ones, and descending

or ascending. Finally, with steam, insects will be effectually kept under in

hothouses, with the gi-eatest ease, by merely keeping the atmosphere of the house chai-ged

with vapour from the tubes for several hours at a time.

2119. T h e disadvantages o f steam as a vehicle f o r conveying heat to hothouses are lew.

On a small scale it is more expensive than the mode by flues, and more trouble is required

to attend to one boiler than to one or even two or three fiirnaces. It is also somewhat

more expensive than heating hy hot water. These ai-c all the disadvantages we know ot.

It has been stated by some that steam draws up or etiolates plants, and lessens the tl^our

of fruits ; but we are inclined to consider such effects, when attendant on plants or firaits

in houses heated by steam, as resulting from some deficiency of management in other

points of culture.