m m ^ '

tribes gi-eater tban tbat of .listrilrating among them the seeds of good fmits and enlmary

vcgetkbles, and teaehing them is eondneive to the health both of

The pleasure attending f “ f g ‘ tpe eujoymcut of gardens is so natural to

the body and of the mmd ; and ^ endearing and most saered associations,

man, as to be ahnost universal. Om h'8 ^ and most refined

Mrs. Hofland observes, ai'o connected w g ^ condition of our be ng

perceptions of beauty are thA pleasures attached to them (Wto®

compels us to the cares and "A '¡y (i„gs, and the choice of philosophers,

Kni^hty.) Gardening has been the ^ iig „ e , after sixty yearn’ experi-

Siv William Temple has passion which augments with ago :—

enoe, affirms, that the love of Y oe mon goût pour les jai-dms. U me

r - ’¿ y , or at least more excusable,

Ä Z t Ä : p o Ä S c r b ’etter who has“a garden of his own, than a neh

man who has none. j n ,„ ™ r i e tv of garden productions, now plants have

To add to the value and extend the va y ^ g the indigenous fruits an d o u lin a^

been iiitrodueed from every by various processes of culture. To

vegetables have been ™ P * '° y s of botany and gardening, numerous books have been

diffuse instruction on the . J premiums held out for rewarding “ dividual

merit; and where professorships 01 imaieooiiv j .=

a part of public instruction. Vunwlcdffe has thus accumulated on die subject

A vmied and voluminous mass of knowledge » acquainted vyrth

of gardening, which must be when it is weU practised for him

who would practise the m’t with j , this knowledge, and to an-ange

by others. To combine as far reference, is theobject of the present

it in a systematic form, adapted »»‘Ij ™ j J j ^ jt a i 'e principally the works of modern

work. The sources ^ d “ sometiiLs recundng to ancient or oon-

British authors . ¿ f "“P Y Y ou^ r“ rely to our own observation and experieiiee ;

tinental a u t h o r s , and occa^iionally, thong J . Britain, but partly also on

a « ^ d u r¡n g ^ e a rly forty years’ practice as a landscape

I * -

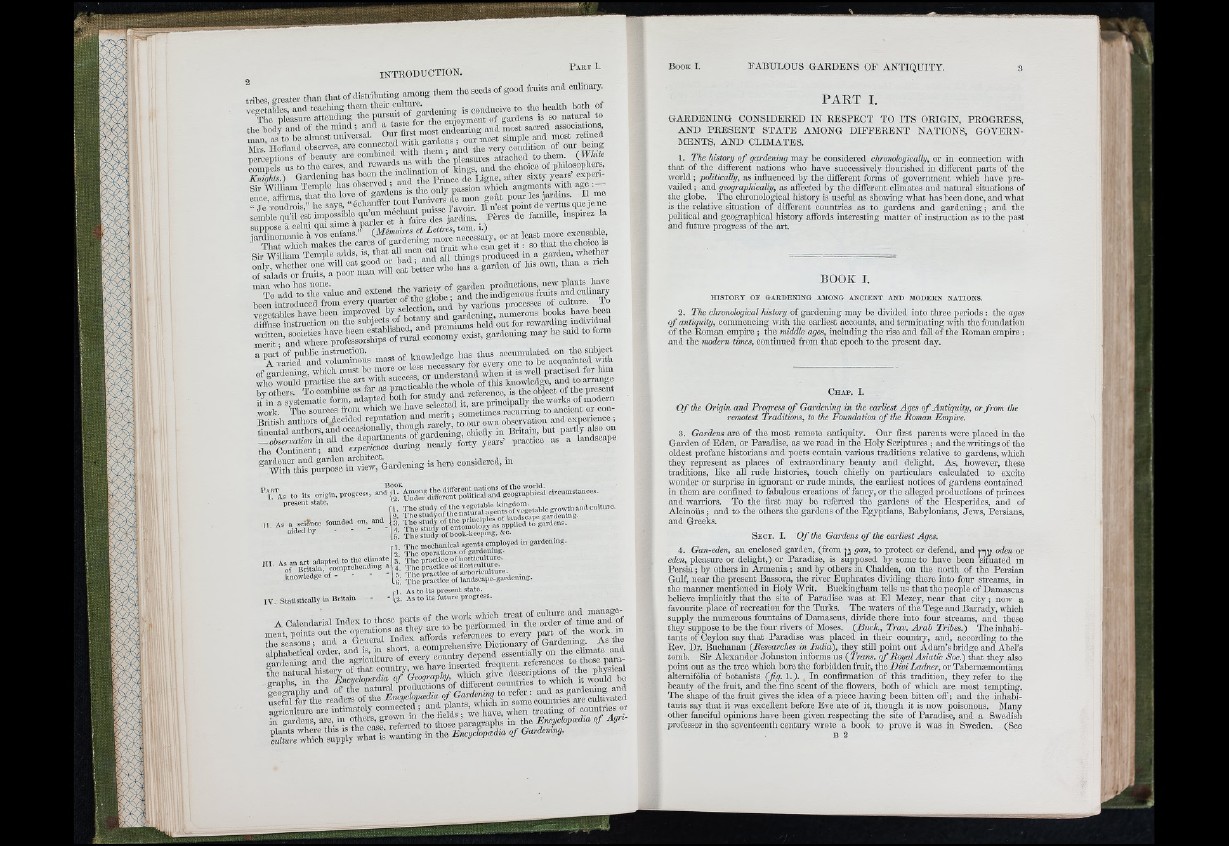

’■‘Y as to its origin, progress, a n il.V o n g y h e ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

present state, '■ ;S ® 'f,* lY S ? « io ta b le groivthand enlture,

^ As a y e i& 11- c e tomided on, and_ aided by

III As an a rt a d ap ted to th e climate

of Britain, comprehending a

knowledge of - -

IV . Statistically in Britain

[r>. The s tu d y of book-keeping, &c.

I T h e mechanical agents employed in gardening.

2' The operations of gardening.

3. The practice of horticulture.

4 The practice of floriculture.

a' The practice of arboriculture.

-6. T h e practice of landscape-gardening,

f] As to its present state.

■ \2 . As to its future progress.

Zo gm p h y and of the natural ^ „ f e r ; and as gardening and

useful for the readers o fth e Enajebpcedta / gome countries are cultivated

• n - r

PART I.

GARDENING CONSIDERED IN RESPECT TO IT S ORIGIN, PROGRESS,

AND PRESENT STA TE AMONG D IF F ER E N T NATIONS, GOVERN-

jVCENTS, a n d CLIMATES.

1. The history o f gardening may be considered chronologically, or in connection with

that of the different nations who have successively flourished in different parts of the

world; politically, as influenced by the different fonns of government which have prevailed

; and geographically, as affected by the different climates and natural situations of

the globe. The chronological Iiistory is useful as showing what has been done, and what

is the relative situation of different countries as to gardens and g ardening; and the

political and geographical history affords interesting matter of instmction as to the past

and futm-e progress of the art.

B O O K I .

HISTORY o r GARDENING A5IONG ANCIENT AND MODERN NATIONS.

2. The chronological history of gardening may be divided into three periods : the ages

o f antiquity, commencing with the earliest accounts, and terminating with the foundation

of the Roman empire ; the middle ages, including the rise and fall of the Roman empire;

and the modern times, continued from that epoch to the present day.

C h a j . I .

O fth e Origin and Progress o f Gardening in the earliest Ages o f Antiquity, or f rm . the

remotest Traditioiis, to the Foundation o f the Roman Empire.

3. Gardens are of the most remote antiquity. Our first pai*ents were placed in the

Garden of Eden, or Pai'adise, as we read in the Holy Scriptures ; and the wi-itings of the

oldest profane historians and poets contain various traditions relative to gai'dens, which

they represent as places of extraordinary beauty and delight. As, however, these

traditions, like all rude histories, touch chiefly on particulars calculated to excite

wonder or sm*prise in ignorant or mdc minds, the earliest notices of gardens contained

in them are confined to fabulous creations of fancy, or the alleged productions of princes

and warriors. To the first may be referred the gai'dens of the Hesperides, and of

Alcinoiis; and to the others the gai'dens of the Egyptians, Babylonians, Jews, Persians,

and Greeks.

S e c t . I. O f the Gardens o f the t

4. Gan-eden, au enclosed garden, (from p gan, to protect or defend, and p y oden or

eden, pleasure or delight,) or Paradise, is supposed by some to have been situated in

P e rs ia ; by others in Armen ia; and by others in Chaldea, on the north of the Persian

Gulf, near the present Bassora, the river Euphrates dividing there into four streams, in

the manner mentioned in Holy Writ. Buclangham tells us that the people of Damascus

believe implicitly that the site of Paradise was at E l Mezey, near that c ity ; now a

favourite place of recreation for the Turks. The waters of the Tege and Barrady, which

supply the numerous fountains of Damascus, divide there into four streams, and these

they suppose to be the four rivers of Moses. {Bu c k, Trav. Arab Tribes.) The inhabitants

of Ceylon say that Paradise was placed in their country, and, according to the

Rev. Dr. Buchanan {Researches in India), they still point out Adam’s bridge and Abel’s

tomb. Sir Alexander Johnston informs us {Trans, o f Royal Asiatic Soc.) that they also

point out as the tree which bore the forbidden fruit, the D iv i Ladner, or TabermEmontkia

alternifdlia of botanists (fig. I.). In confirmation of this tradition, they refer to the

beauty of the fruit, and the fine scent of the flowers, both of which are most tempting.

The shape of the fruit gives the idea of a piece having been bitten o ff; and the inhabitants

say that it was excellent before Eve ate of it, though it is now poisonous. Many

other fanciful opinions have been given respecting the site of Pai'adise, and a Swedish

professor in the seventeenth century wrote a book to prove it was in Sweden. (See

t : : k-U