r ' ■ 1 ■ 1

: :

Ll'

monarch has made some additions to it. Oi' tho garden, however, we hear nothing till the time of

Henry V„ when it was celebrated by James I. of Scotland in a poem he wrote wliilc he was a prisoner

in th e castle. (See §551.) In the time of Queen Elizabeth the principal terrace was formed on the

north side of th e castle; and in tho time of Charles II. this terrace was carried round to the east and

p art of th e south front. In tlie time of William and Mary tho L ittle Park was enclosed by a brick

w a ll; and in the time of this monarch and his successor, Queen Anne, various avenues of elms and

clumps of forest trees were p lan ted ; but though these monarchs improved the parks they do not appear

to have paid any attention to the gardens. Various plans, however, were suggested from time to time

for furnishing Windsor with gardens and pleasure-grounds worthy of the magnificence of th e castle ;

and amongst otliers Whately, the weU-known author of the Obsei'vations on Modern Gardening, loft a

manuscript, written in 1772, and which was many years afterwards published in th e Gardener's Magn-

xinc by pennission of his family, in which he gave a detailed account of a plan which he had conceived

of rendering th e grounds around the castle some of the most magnificent in Europe. “ A more magnificent

and delightful royal residence,” he observes, “ can hardly be imagined than th a t of Windsor

Castle. The eminence on which th e castle stands is detached from every other, and advanced into the

plain which it commands ; it falls in a bold slope on one side, while it is easy of access on th e other ; and

as the palace occupies almost all the brow, the whole hill seems but a base to the building. It rises in

th e midst of an enchanting country, and it is there th e m ost distinguished s p o t; but though the situation

is singular, it is not ex trav ag an t; it is great, but not wild. It is in itself noble, and all around it

is beautiful. The view from the terrace is not the most picturesque, but it is th e gayest th at can be

conceived. The Thames diffuses a cheerfulness through all th e counties where it flows, and this is in

itself peculiarly cheerful. It is luxuriantly fe rtile ; it is highly cu ltiv a ted ; it is full of villas and

villages; and they are scattered all over it, not crowded together : no hurry of business appears ; and

no dreary waste is in s ig h t; country churches and gentlemen’s seats are every where intermixed with

th e fields and the trees. Every spot seems improved, but improved for the purposes of pleasure: all

are r u r a l ; none are so lita ry ; and tho amenity of th e plain is at tho same time contrasted with the ricii

woods in the Great P ark , their height, th eir shade, and th e ir verdure.” (See Gard. Mag., vol. vii.

p. 146.) The Great P ark is eighteen miles in circumference, and both it and th e L ittle P ark are full of

large trees, m ost of which are arranged in avenues. The space these avenues enclose, W hately observes,

may be divided into three parts. “ The declivities of the hill towards Frogmore and Datchct are comprehended

within one of these divisions; th e level from th e foot of the hill towards Datchet constitutes

the second; and all the plain which borders on th e Thames from Datchet to Eton bridge is

included in th e th ird .” In the first of these divisions th e ground varies considerably. Ancient oaks

and lofty elms are scattered about, sometimes crowning th e brow of the descemt, and a t others giving

richness to th e valleys. Among these trees appear different views of the towers of th e castle, and

from some points two fronts may be seen a t once in perspective. T h e beauties in the second di-

vison are of a tamer c h a ra c te r: the castle is entirely hid, and th e principal point of importance is a

little watercourse which might be easily converted into a rivulet. T h e plain between the castle and

th e Thames is remarkably rich ; and it is on this side th a t th e slopes are situated, which, in the latter

p art of the reign of George II I., were converted into a garden. On th e other side of the Great Park

is Windsor Forest, a vast tra c t of land which exhibits almost every possible variety of scenery; and, in

fact, th e whole of th e domain exhibits a scene of elegance and grandeur probably unequalled in any

other part of Great Britain.

The slopes which form the declivity of the hill, forming the north terrace, were first enclosed in the

reign of George I I I . ; b u t pleasure-grounds, about eighteen acres in extent, have been recently laid out

adjoining them.

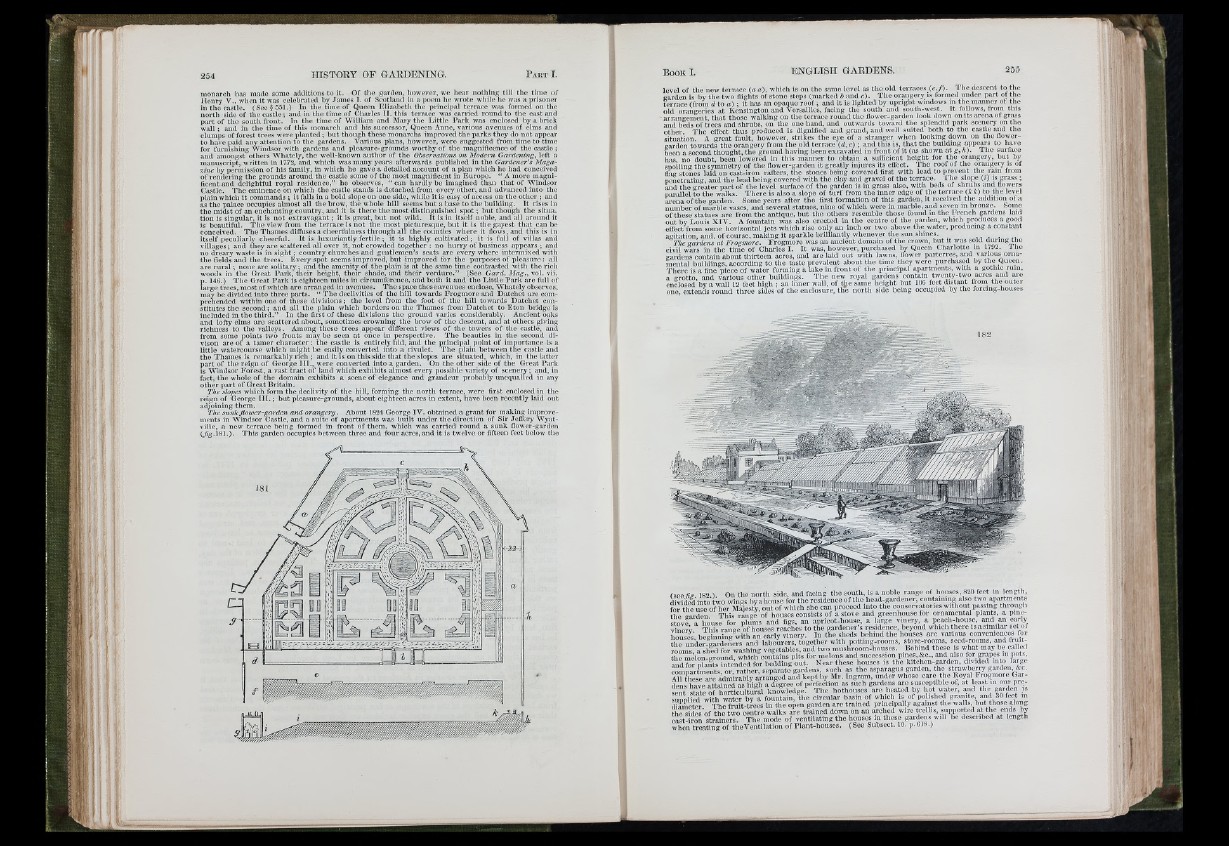

The sunk flouiei'-garden and orangery. About 1824 George IV. obtained a grant for making improvements

in Windsor Castle, and a suite of apartments was built under the direction of Sir Jellery Wyat-

villc, a new terrace being formed in front of them, which was carried round a sunk flower-garden

(y?g.l81.). This garden occupies between three and four acres,and it is twelve or fifteen feet below the

level of th e new terrace (a a), which is on the same level as th e old terraces ( c ,f ) . The descent to the

garden is by th e two flights of stone steps (marked b and c). T h e orangery is lormed under part of the

terrace (from d to o) ; it has an opaque ro o f; and it is lighted by upright windows m the manner ot the

old orangeries a t Kensington and Versailles, facing the south and south-west. It Iqllows, from this

arrangement, th a t thoso walking on the terrace round the flower-garden look down on its arena of grass

and beds of trees and shrubs, on th e one hand, and outwards toward th e splendid park scenery on tlie

other The effect thus produced is dignified and grand, and well suited both to the castle and the

situation. A great fault, however, strikes th e eye of a stranger when looking down on the flower-

garden towards the orangery from the old terrace (d, e) ; and this is, th at the building appcars to have

been a second thought, th e ground having been excavated in front of it (as shown at g ,h ). The surface

has no doubt been lowered in this manner to obtain a sufficient height for th e orangery, but by

snoiling th e symmetry of th e flower-garden it greatly injures its effect. T h e roof of the orangery is of

flag stones laid on cast-iron rafters, the stones being covered first with lead to prevent the ram from

nenetrating, and th e lead being covered with th e clay and gravel of th e terrace. T he slope (0 is grass ;

mid the greater part of the level surface of th e garden is in grass also, with beds of s h r ^ s and flowers

parallel to the walks. T h ere is also a slope of tu rf from the inner edge of the terrace (,/ck) to th e level

arena o fth e garden. Some years after the first formation of this garden, it received the addition of a

number of marble vases, and several statues, nine of which were in marble, and seven in bronze, some

of these statues are from th e antique, but th e others resemble those found m the I rench p rd e n s laid

out bv Louis X IV. A fountain was also erected in the centre of the garden, which produces a good

effect from some horizontal jets which rise only an inch or two above the water, producing a constant

agitation, and. of course, making it sparkle brilliantly whenever the sun shines.

The sardens at Frogmore. Frogmore was an ancient domain of the crown, but it was sold during the

civil wars in th e time of Charles I. It was, however, purchased by Queen Charlotte m 1792. I h e

gardens contain about thirteen acres, and arc laid out with lawns, flower parterres, and various ornamental

buildings, according to the taste prevalent about th e time they were purchased by the Queen.

T h ere is a fine piece of water forming a lake in front of the principal apartments, with a gothic rum,

a grotto, and various other buildings. The new royal gardens contain twenty-two acres and are

enclosed by a wall 12 feet high ; an inner wall, of the same height but 106 feet distant from_ the outer

one extends round three sides of the enclosure, th e north side being occupied by the forcmg-liouses

isPP/i-r 182 ) On tho north side, and facing the south, is a noble range of houses, 820 feet m length,

dWidcdintotWo wings byahouse for the residence of the head-gardener, containing also two, apartments

f / r t h e u ^ oHier Mrijesty, out of which she can proceed into th e conservatories without passing through

th e g / r d S ™ r r a i ! g e of houses consists of a stove and greenhouse for ornamental plants, a pine-

s t o v f a h /u se for phfms and figs, an apricot-house, a large vinery, a peato-house, an d .a n early

I S v This range of houses reaches to the gardener’s residence, beyond which there is a similar set ol

houses' beginmng with an early vinery. In the sheds behind th e houses arc various conveniences for

tlm u /d e r-g a rd e /c rs and labourers, together with potting-rooms, store-rooms, seed-rooms, and fruic-

ro?ms a /h /d for washing vegetables, and two mushroom-houses. Behind those is what may be callod

the melon-ground which contains pits for melons and succession pines, &c., and also for grapes m pots,

a n d f o rX / t s S n d e d for bedding out. Near these houses is the kitchen-garden, divided into large

X m p a r t m e n t s s e p a r a t e gardens, such as the asparagus garden, the strawbeiry garden, &c.

A lU h e s 3 ? e admirably arranged and kept by Mr. Ingram, under whose care the Royal Frogmore Gardens

have atta"^^^^ a degree of perfection as such gardens are susceptible of, a t ^ s t m our pro-

S t state of horticultufal knowledge. The hothouses are heated by hot water, and the g a r ^ n is

supplied with water by a fountain, the circular basm of which is of polished granite, and 30 feet in

diameter T h e fruit-trees in the open garden are trained principally against the walls, but those along

the sides'of the two centre walks are trained down on an arched wire trellis, supported a t ^ ^ s by

cast-iron strainers. T h e mode of v e n til^ n g the ^ u s e s in these gardens will be described a t length

when treating of the Ventilation of P lant-houses. (See Subsect. 10. p. 618.)

li