l i

' I

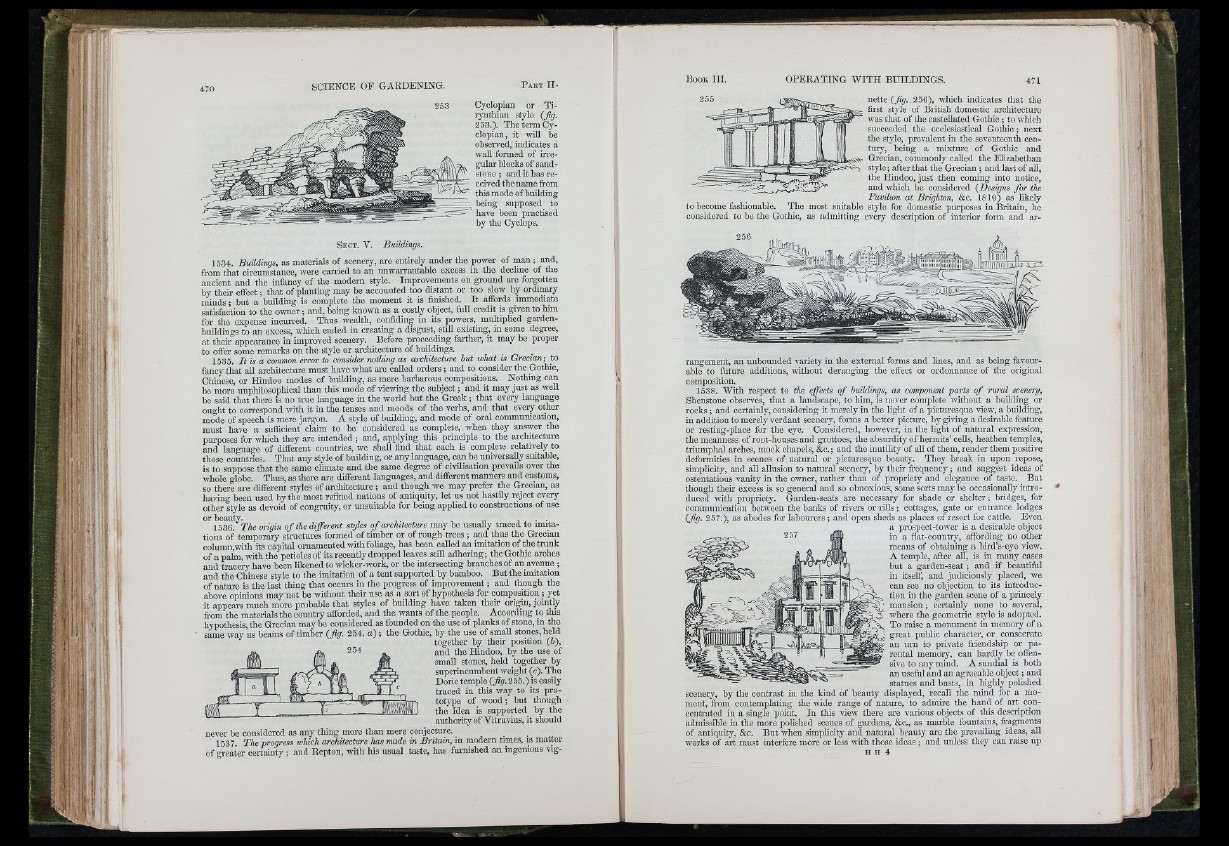

253 Cyclopian or Ti-

rynthian style (fig.

253.). The term Cyclopian;

it wiU be

observed, indicates a

wall formed of irregular

blocks of sandstone

; and it has received

the name from

this mode of building

:___ being supposed to

have been practised

hy the Cyclops.

S e c t . V . Buildings.

1534. Buildings, as materials of sceneiy, ai*e entirely under the power of man ; and,

from that circumstance, were carried to an unwarrantable excess in the decline of the

ancient and the infancy of the modern style. Improvements on ground arc forgotten

by their effect; that of planting may be accounted too distant or too slow hy ordinary

min d s; hut a building is complete the moment it is finished. I t affords immediate

satisfaction to the owner; and, being known as a costly object, full credit is given to him

for the expense incurred. Thus wealth, confiding in its powers, multiplied garden-

buildings to an excess, which ended in creating a disgust, still existmg, in some degree,

at their appearance in improved scenery. Before proceeding farther, it may he proper

to offer some remarks on the style or architecture of buildings.

1535. I t is a common error to consider nothing as architecture hut what is Grecian; to

fancy that all architecture must have what are called ord ers; and to consider the Gothic,

Chinese, or Hindoo modes of building, as mere barbarous compositions. Nothing can

be more unphilosophical than this mode of viewing the subject; and it may just as well

be said that there is no true language in the world but the G re ek ; that every language

ought to correspond -with it in the tenses and moods of the verbs, and that every other

mode of speech is mere jargon. A style of building, and mode of oral communication,

must have a sufficient claim to be considered as complete, when they answer the

purposes for which they are intended ; and, applying this principle to the architecture

an d language of different countries, we shall find that each is complete relatively to

those countries. Th a t any style of building, or any language, can be universally suitable,

is to suppose that the same climate and the same degree of civilisation prevails over the

whole globe. Thus, as there are different languages, and different manners and customs,

so there are different styles of architecture ; and though we may prefer the Grecian, as

having been used b y th e most refined nations of antiquity, let us not hastily reject every

other style as devoid of congruity, or unsuitable for being applied to constructions of use

1536.* The origin o fth e different styles o f architecture may be usually traced to imitations

of temporary structures formed of timber or of rough trees ; and thus the Grecian

column,with its capital ornamented with foliage, has been called an imitation of the trunk

of a palm, with the petioles of its recently dropped leaves stiU adhering; the Gothic arches

and tracery have been likened to wicker-work, or the intersecting branches of an avenue ;

aud the Chinese style to the imitation of a tent supported hy bamboo. But the imitation

of natm-e is the last thing that occurs in the progress of improvement; and though the

above opinions may not be without their use as a sort of hypothesis for composition; yet

it appears much more probable that styles of building have taken their origin, jointly

from the materials the country afforded, and the wants of the people. According to this

hypothesis, the Grecian may be considered as founded on the use of planks of stone, in the

same way as beams of timber (fig. 254. a ) ; the Gothic, by the use of small stones, held

together by their position (h),

254 _ and the Hindoo, by the use of

small stones, held together by

superincumbent weight (c). The

Doric temple (fig. 255.) is easily

traced in this way to its prototype

of wood; hut though

the idea is supported by the

authority of Vitruvius, it should

never be considered as any thing more than mere conjecture. _

1537. The progress which architecture has made in Britain, in modern times, is matter

of greater ce rtainty; and Repton, with his usual taste, has furnished an ingenious vignette

(fig. 256), which indicates that the

first style of British domestic architecture

was that of the castellated Gothic; to which

succeeded tlie ecclesiastical Gothic; next

the style, prevalent in the seventeenth century,

beiug a mixture of Gothic and

Grecian, commonly called the Elizabethan

style; after that the Grecian ; and last of aU,

the Hindoo, just then coming into notice,

and which he considered (Designs fo r the

Pavilion at Brighton, &c. 1810) as hkely

to become fashionable. The most suitable style for domestic pm-poses in Britain, lie

considered to be the Gothic, as admitting every description of interior form and ai--

rangement, an unbounded vai-iety in the external forms and lines, and as being favourable

to future additions, without deranging the effect or ordonnance of the original

composition.

1538. With respect to the effects o f buildings, as component parts o f rural scenery,

Shenstone observes, that a landscape, to him, is never complete without a building or

ro ck s; and certainly, considering it merely in the light of a picturesque view, a building,

in addition to merely verdant scenei-y, forms a better picture, by giving a desirable featm-e

or resting-place for the eye. Considered, however, in the light of natural expression,

the meanness of root-houses and grottoes, the absurdity of hermits’ cells, heathen temples,

tiiumphal arches, mock chapels, &c.; and the inutOity of all of them, render them positive

deformities in scenes of natural or pictm-esque beauty. They break in upon repose,

simplicity, and all allusion to natm-al scenery, by their frequency; and suggest ideas of

ostentatious vanity in the owner, rather than of propriety and elegance of taste. But

though theu- excess is so general and so obnoxious, some sorts may be occasionally introduced

with propriety. Garden-seats are uecessai-y for shade or shelter; bridges, for

communication between the banks of rivers or rills ; cottages, gate or entrance lodges

(fig. 257.), as abodes for labourers; and open sheds as places of resort for cattle. Even

a prospect-tower is a desirable object

in a flat-country, affording no other

means of obtaining a bird’s-eye view.

A temple, after all, is in many cases

but a garden-seat; and if beautiful

in itself, and judiciously placed, we

can see no objection to its introduction

in the garden scene of a princely

mansion; certainly none to several,

where the geometric style is adopted.

To raise a monument in memory of a

great public character, or consecrate

an um to private friendship or parental

memoi-y, can hardly be offensive

to any mind. A sundial is both

an useful and an agreeable object; and

statues and busts, in liighly polished

scenery, by the contrast in the kind of beauty displayed, recall the mind for a moment,

from contemplating the wide range of nature, to admire the hand of art concentrated

in a single point. In this view there are various objects of this description

admissible in the more polished scenes of gardens, &c., as mai-blc fountains, fragments

of antiquity, &c. But when simplicity and natural beauty are the prevailing ideas, all

works of art must interfere more or less with those id e as; aud unless they can raise up

H H 4