i ï

I i. ;

t i H i

i !

m

r , I !

>1

ii'î

!ré

L ■ I

i< i ■

• i

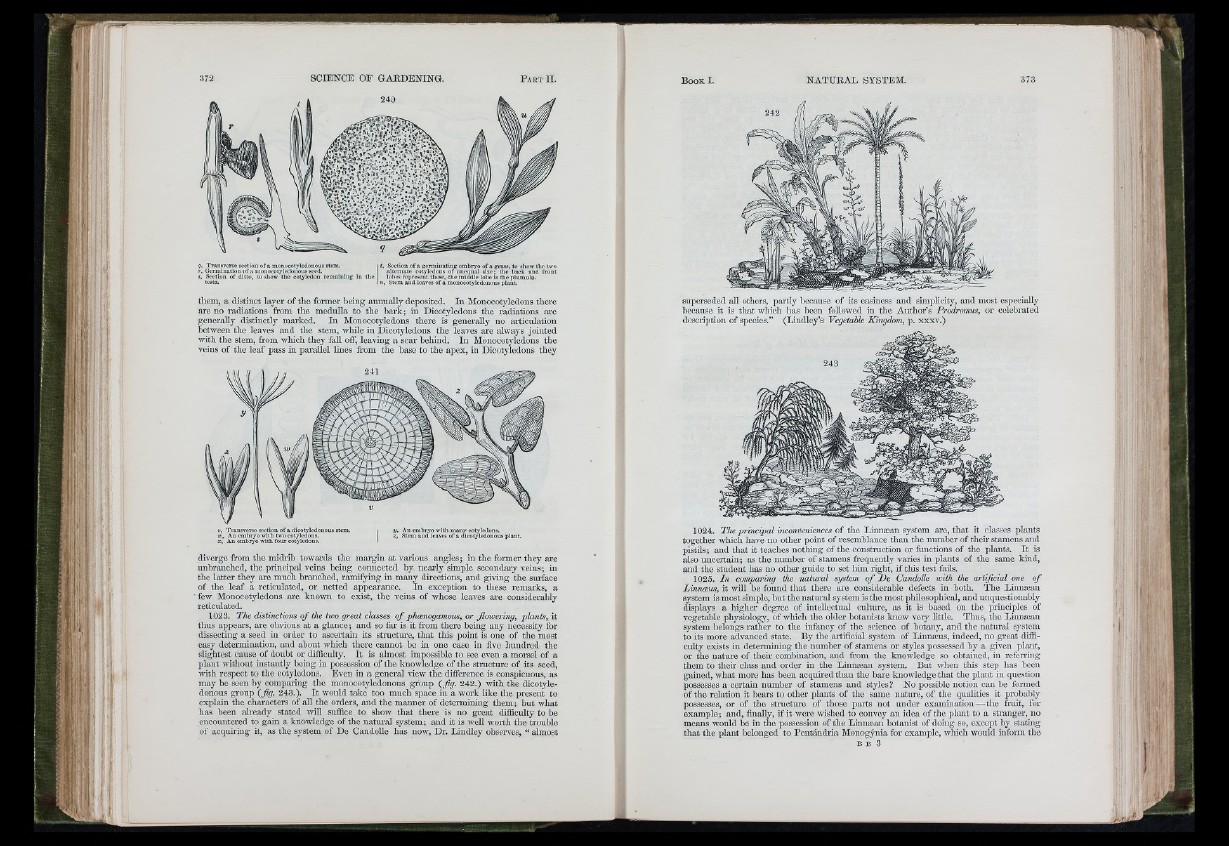

g. Transverse section of a monocotyledonous stem. t, Section of a g erm in atin g embryo o f a grass, to show th e two

>•, Germination of a monocotyledonous soc<l. alUTnatc cotyledons of u n equal size; th e back an d fro n t

, Section o f ditto, to show th e cotyledon rem a in in g in the lolies represent these, the mid<llc lobe is th e plumula.

testa. K, Stem a n d leaves o f a monocotyledonous plant.

them, a distinct layer of the former being annually deposited. In Monocotyledons there

are no radiations from the medulla to the hark; in Dicotyledons the radiations ai'c

generally distinctly marked. In Monocotyledons there is generaUy no articulation

between the leaves and the stem, wliile in Dicotyledons the leaves are always jointed

with the stem, from which they fall off, leaving a scar behind. In Monocotyledons the

veins of the leaf pass in pai-allel lines from the base to the apex, in Dicotyledons they

acotyledons.

cotyledonous plant.

diverge from the midiib towards the margin at various angles; in the foimer they are

unbrauched, the principal veins being connected by neaily simple secondaiy veins; in

the latter they ai-e much branched, ramifying in many directions, and giving the surface

of the leaf a reticulated, or netted appearance. In exception to these remarks, a

few Monocotyledons are known to exist, the veins of whose leaves ai-e considerably

reticulated.

1023. The distinctions o fth e two great classes o f phcenogamous, or flowering, plants, it

thus appears, are obrious at a glance; and so far is it from there being any necessity for

dissecting a seed in order to ascertain its structure, that this point is one of the most

easy determination, and about which there cannot be in one case in five hundred the

slightest cause of doubt or difficulty. I t is almost impossible to see even a morsel of a

plant without instantly being in possession of the knowledge of the structure of its seed,

with respect to the cotyledons. Even in a general view the difference is conspicuous, as

may be seen by compaiing the monocotyledonous group (fig. 242.) with the dicotyledonous

gi’oup (fig. 243.). It would take too much space in a work like the present to

explain the characters of all the orders, and the manner of dctennining them; but what

has been already stated will suffice to show that there is no great difficulty to be

encountered to gain a knowledge of the natural system; and it is well worth the trouble

of acquiring it, as the system of Dc Candolle has now, Dr. Lindley observes, “ almost

supei-seded all others, partly because of its easiness and simplicity, and most especially

because it is that which has been followed in the Author’s Prodromus, or celebrated

description of species.” (Lindley’s Vegetable Kingdom, p. xxxv.)

1024. The principal inconveniences oi the Linnæan system ai'c, that it classes plants

together which have no otlier point of resemblance than the number of their stamens and

pistils ; and that it teaches nothing of the constmction or functions of the plants. I t is

also uncertain ; as the number of stamens frequently varies in plants of the same kind,

and the student has no other guide to set him right, if this test fails.

1025. In comparing the natural system o f De Candolle with the artificial one o f

Linnæus, it will be found that there are considerable defects in both. The Linnæan

system is most simple, but the natm-al system is the most philosophical, and unquestionably

displays a higher degi-ee of intellectual culture, as it is based on the principles of

vegetable physiology, of which the older botanists knew vei-y little. Thus, the Linnæan

system belongs rather to the infancy of the science of hotany, and the natural system

to its more advanced state. By the artificial system of Linnæus, indeed, no gi-cat difficulty

exists in detei-mining the number of stamens or styles possessed by a given plant,

or the nature of their combination, and from the knowledge so obtained, in refening

them to their class and order in the Linnæan system. But when tliis step has been

gained, what more has been acquired than the bai-e knowledge that the plant in question

possesses a certain number of stamens and styles? No possible notion can be foi-med

of the relation it bears to other plants of the same nature, of the qualities it probably

possesses, or of the stmcture of those parts not under examination—the fmit, for

example; and, finally, if it were wished to convey an idea of the plant to a stranger, no

means would be in the possession of the Linnæan botanist of doing so, except by stating

that the plant belonged to Pentandi-ia Monogÿnia for example, which would inform the

B B 3

tall I