fourteen inches across and twelve inches deep ; quite perpendicular, with shai-p cutting

edges and a hilt or piece of iron (a) riveted on for the feet. F o r the stubbing of

hedges, taking the top sods off drains, and various uses where strength is wanted, this

spade will be tbund a most powei-ful instrument.

i 696. The tu r f spade {fig. 328. p. 518.) consists of a cordate or scutiform blade, joined to

a handle by a kneed or bent iron shank. It is used for cutting tu rf from old sheep-

pasturcs, with a view to its being employed either for tui-fing garden-grounds, or bcuig

thrown together in heaps to rot into mould. I t is also used in removing ant-hills and

^ other inequalities in sheep-pastiu-cs, in parks,

rough lawns. A thin section often is first

removed, then the protuberance of eai’th be-

neath it is taken out, and the section is re-

V“ placed, which, having been cut thin, espe-

^ ^ 5 = ^ cially on the edges, readily refits; and the

operation is finished by a gentle pressure by the foot, back of the spade, beetle, or roller.

Cue vai’iety of the turf-spade {fig. 316.) has one edge turned up, and made quite shai-p :

this spade is preferable where the tui-ves are to be cut square-edged, and somewhat thick.

1697. The shovel {fig. 307.) consists of two pai’ts, the handle and the b la d e ; the latter

of platc-iron, and the former of ash timher. There are several varieties : such as ai’e

tm’ned up on the edges, and are used for shovelling mud, or, when formed of wood (generally

of beech), for turning grain, seeds, or potatoes; squai’e-mouthed shovels, for

gathering up dung in stables, and used by gardeners in the melon-ground; heart-

shaped or pointed-mouthed shovels, used for lifting eai’th out of trenches, in ditch-making,

trenching, or in other excavations; and long naiTOw-mouthed shovels, for cleaning out

drains, &c.

1698. The fo rk {figs. 308, 309, and 310.). Of this tool there arc three principal

species:— The first ( /p . 308.), for workmg -with litter, haulm, or stable-dung; the

second {fig. 309.), for stin-ing the earth among numerous roots, as in fruit trees and

flower-borders, or for taking up roots; and the third {fig. 310.), for plunging pots in

bark-pits, or for taking up aspai’agus or other roots. The prongs of the last ai’e small

and round, and should be kept clear or polished hy use, or by friction with sand. In

adhesive soils, a strong two-pronged fork {fig. 309.) is one of the most useful of garden-

tools, and is advantageously used on most occasions where the spade or even the hoe

W'ould he resorted to in free soils, but especially in stirring between crops.

1699. The dibher (Jigs. 311, and 312.) is a short piece of cylindrical wood, obtusely

pointed, and sometimes shod with fron on the one end, and formed into a convenient

spade-like handle in the other. There are three species. The common garden-dibber

(fig. 311.), the potato dibber (fig. 312.), and the forester’s or planter’s dibber. The

forester’s dibber has a wedge-shaped blade, forked at the extremity, for the purpose of

can-ying down with it the tap-root of seedling trees, aud has been much used in planting

extensive tracts. There are also dibbers that make two holes at once, sometimes used

in planting leeks or other ai’ticles that are placed within a few inches of each o th e r;

dibbers which make several holes for planting beans and other seeds; and wedge-shaped

dibbers which in soft sandy soils are easily worked, and admit of spreading the roots

better than the round kind. These wedge-shaped tools also admit of putting two plants

in a hole, one at each extremity.

1700. The perforator {fig. 317.) is tried as a substitute for the spade, in planting

young tap-rooted trees in rough ground. I t was invented by Mr. Munro, formerly of

the Bristol Nursery, and costs in that part of the country about 8s. In using it, one

man employs the instrument, while another man or boy holds a bundle of plants. The

man first inserts the instrument in the soil, holding it up for the reception of the p la n t;

round which, whan introduced, he inserts the iron three times, in order to loosen the

soil about the ro o ts; then treads down the tuif, and the plant becomes as fimily set in

the ground as if it had been long planted. Two men will set in one day from 500 to

600 plants with this instromcnt, at Is. per h u n d red ; whereas, by digging holes, the

expense would be 3s. per hundred, and the planting not done so well. {Gard. Mag.,

vol. iii. p. 215.)

1701. The tree-planter's hack, or double mattock, is used for the same purpose

as the forester’s dibber, and is much to be prefen-ed. (See Pontey's Profitable

Planter.)

1702. The tree-planter’s trowel i s a t r i a n g u l a r b l a d e o f i r o n j o i n e d t o a s h o r t h a n d l e ,

u s e d f o r p l a n t i n g y o u n g t r e e s i n f r e e b u t u n p r e p a r e d s o ils , a s h e a t h s , m o o r s , & c . {Sang's

Planter's Kalendar.)

1703. The forester's pickaxe is tbe tool of that name {fig. 302.) inminiatm-e ; or sometimes

merely a small mattock (fig. 303.J) used for planting in stony uncultivated soils.

1704. The gardm-trowel is a tongue-shaped piece of iron, Avith a handle attached;

the blade or tongue being semicylindrical {fig. 313.), or merely turned up on the sides.

It is used to plant, or to take up for transplanting, herbaceous plants and small trees.

Trowels are also used for loosening the roots of weeds, and are then called Aveediug-

irons. Sometimes they are used for stirring tbe soil among tender plants in confined

situations. Wooden troAvcls, or spatula), ai’e sometimes used in potting plants to fill

in the e a rth ; but the gai’den-troAvel Avith the edges turned up is the best for tliis

purpose.

1705. The flower transplanter {fig. 314.) c o n s i s t s o f tw o s e m i c y l i n d r i c a l p i e c e s o f i r o n

AAUth h a n d l e s , a n d Avhich a r e s o i n s e r t e d i n t h e g r o u n d a s t o e n c lo s e a p l a n t Avith a b a l l

o f e a i’t h b e tw e e n t h e m . In t h i s s t a t e t h e y a r e a t t a c h e d t o e a c h o t h e r b y tw o i r o n p in s ,

a n d , b e i n g p u l l e d u p , b r i n g Avith t h e m t h e p l a n t t o b e r e m o v e d , s u r r o u n d e d b y a b a l l o f

e a i t l i . T h i s b e i n g s e t i u a p r e p a r e d e x c a v a t i o n s u n - o u n d e d b y lo o s e e a r t h , t h e t r a n s p

l a n t e r i s t h e n s e p a r a t e d a s a t f i r s t , a n d , b e i n g AvithdraAvn, o n e h a l f a t a t im e , t h e e a r t l i

i s g e n t l y p r e s s e d t o t h e b a l l c o n t a i n i n g t h e p l a n t , a n d t h e Avhole Avell w a t e r e d . T e n d e r

p l a n t s t h u s t r a n s p l a n t e d r e c e iv e u o c h e c k , e v e n i f i n f lo w e r . O n e o f t h e b e s t o f t h e s e i n s

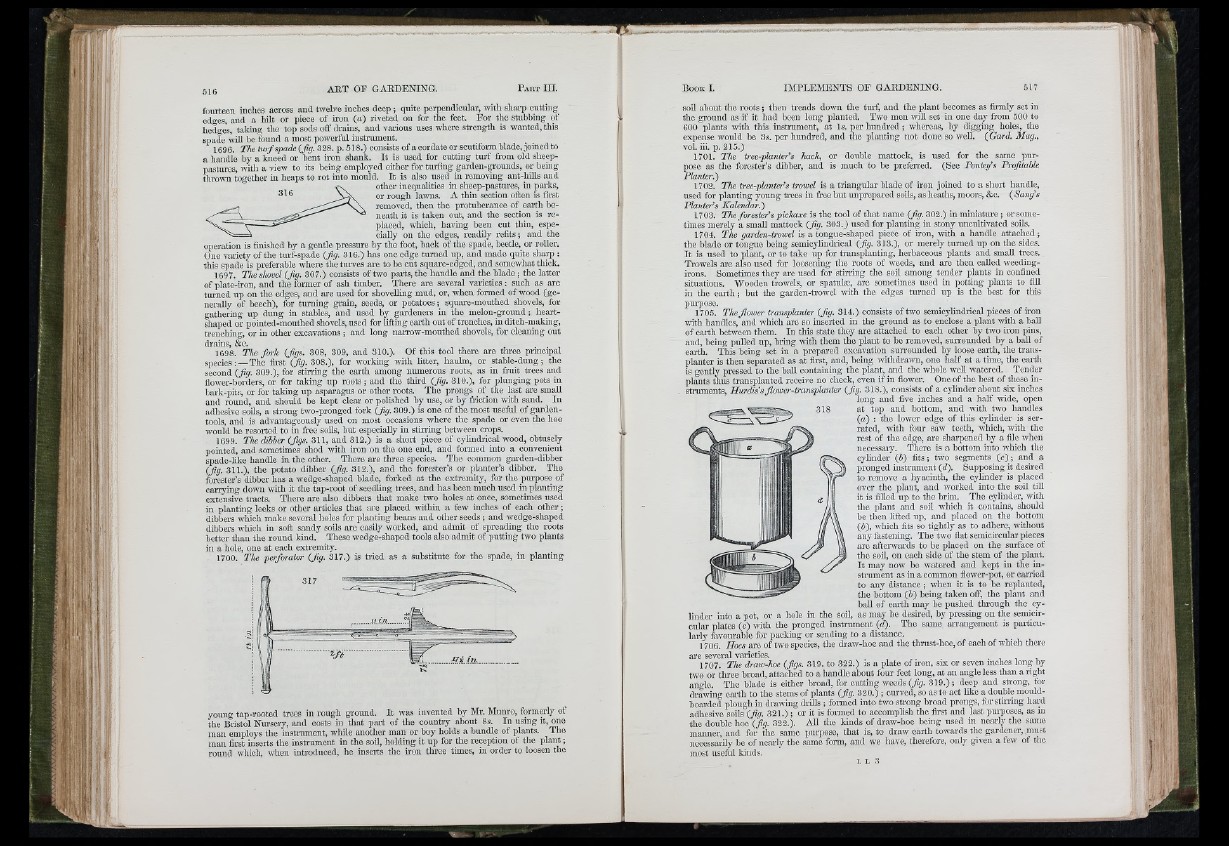

t r u m e n t s , Hurdis's Jiower-transplanter {fig. 318.), c o n s i s t s o f a c y l i n d e r a b o u t s i x in c h e s

l o n g a n d f iv e i n c h e s a n d a h a l f w id e , o p e n

a t t o p a n d b o t t o m , a n d w i t b tw o h a n d l e s

( a ) : t h e loAvcr e d g e o f t h i s c y l i n d e r i s s e r r

a t e d , w i t h f o u r saAv t e e t h , w h i c h , Avith t h e

r e s t o f t h e e d g e , a r e s h a i - p e n e d b y a f i le w h e n

n e c e s s a i-y . T h e r e i s a b o t t o m i n t o w l i i c h t h e

c y l i n d e r ( 6 ) f i t s ; tAvo s e g m e n t s ( c ) ; a n d a

p r o n g e d i n s t n im e n t {d). S u p p o s i n g i t d e s i r e d

t o r e m o v e a h y a c i n t h , t h e c y l i n d e r i s p l a c e d

o v e r t h e p l a n t , a n d A v o rk e d i n t o t h e s o i l t i l l

i t is f i l l e d u p t o t h e b r im . T h e c y l i n d e r , w i t h

t h e p l a n t a n d s o i l w l i i c h i t c o n t a in s , s h o u l d

b e t h e n l i f t e d u p , a n d p l a c e d o n t h e b o t t o m

{b), AA'hich f i t s s o t i g h t l y a s t o a d h e r e , w i t h o u t

a n y f a s t e n i n g . T h e tAvo f l a t s e m i c i r c u l a r p i e c e s

a r e a f t c n v a i ’d s t o b e p l a c e d o n t h e s u r f a c e o f

t h e s o d , o n e a c h s i d e o f t h e s t e m o f t h e p l a n t .

I t m a y n o w b e w a t e r e d a n d k e p t i n t b e i n s

t r u m e n t a s i n a c o m m o n floA v e r -p o t, o r c a r r i e d

t o a n y d i s t a n c e ; Avhen i t is t o b e r e p l a n t e d ,

t h e b o t t o m {b) b e i n g t a k e n o ff, t h e p l a n t a n d

b a l l o f e a i ’t h m a y b e p u s h e d t h r o u g h t h e c y l

i n d e r i n t o a p o t , o r a h o l e i n t h e s o i l , a s m a y b e d e s i r e d , b y p r e s s i n g o n t h e s e m i c i r c

u l a r p l a t e s ( c ) Avith t h e p r o n g e d i n s t r u m e n t { d ) . T h e s a m e a i - r a n g e m e n t i s p a r t i c u l

a r l y f a v o u r a b l e f o r p a c k i n g o r s e n d i n g t o a d i s t a n c e .

1706. Hoes a r e o f two s p e c ie s , the draw-hoe and the thrust-hoc, o f each o f Avhich there

a i ’e s e v e r a l v a r i e t i e s . _ . , , ,

1707. The draw-hoe {figs. 319. to 322.) is a plate of iron, six or seven mches long by

two or three broad, attached to a handle about four feet long, at an angle less than a right

angle. Tho blade is either broad, for cutting weeds ( fg . 319.) ; deep and strong, for

drawing eai-th to the stems of plants ( fg . 320.) ; curved, so as to act like a double mould-

boarded plough in drawing drills ; formed into two strong broad prongs, for stin-ing hard

adhesive soils (fig. 321.); or it is fomed to accomplish the first and last pui-poses, as m

the double hoe (fig. 322.). All tho kinds of draw-hoe being used in neai-ly the same

manner, and for the same purpose, that is, to draw earth towards tho gardener, must

necessarily be of nearly tbe same form, and we have, therefore, only given a few of tbe

most useful kinds.