I • í r é :

■ r é

: ' IÏ .

must be cut so as to leave a little of the skin to each piece, for by that alone they germinate ; the roots

having no apparent buds or eyes, but casting out their weakly stems from every part of th e surface alike.

They are planted commonly m August, and are ripe in November or December following.”

49G.5. The Sp a n ish , or Stveet Potato, is th e Convdlvulus Batatas L . {Ilheed. M a i. 7. t. 50.); P e n t.

Monog. L. and Gonuolvuldceis B. P . 849.). It is an herbaceous perennial, with a round stem,

hispid, prostrate, creeping, o f a whitish green, putting out scattered, oblong, acuminated tubers, purple

or pale, on the outsides. The leaves are angular, on long petioles ; the flowers purple on upright peduncles.

It is a native of hoth the Indies, and was introduced here, and cultivated by Gerard in 1597.

He calls the roots potatus, potades, or potatoes, and says, that theya re by some named skirrets of P eru .

They flourished in his garden till winter, when they perished and rotted. Batatas were then sold at th e

exchange in London, and are still annually imported into England from Spain and P ortugal. They

were, as already observed (3598.), the common potatoes of our old English writers ; the Solànum tube-

ròsum being then little known. The tubers o f the batatas are sweet, sapid, and nourishing. They arc

very commonly cultivated in all the tropical climates, where they eat not only the roots, but tho young

leaves and tender shoots boiled, There are several varieties, if not distinct species, differing in th e size,

figure, and taste of th e roots.

49G6. Pro p a g a tio n a n d c u ltu r e . In warm climates this plant is cultivated in the same manner as our

Eotato, hut requires much more room, for the trailing stalks extend 4 ft. or 5 ft. every way, sending out

irge tubers, forty or fifty to aplant. In the gardens at Paris, th ep lan tsa re propagated by cuttings struck

in a hotbed, and about the middle of May transplanted into th e open ground, where they are earthed up,

and otherwise treated like the potato.

49G7. The O'xalis c r e n a ta J ac. { S w .f i . ga n \ 9. s. 125. De cá n . P e n ta g . L. and Oxalidece J . ) was introduced

into England from Lima in 1829. It grows freely in the open air in the .summer season, but is

easily destroyed by frost. In autumn, when the weather begins to grow cold, the points of its underground

stolones form themselves into tubers, which are edible, and contain a good deal o f saccharine

matter. It has been proposed to use these tubers like the potato ; the foliage in salad ; and the stems in

tarts. The whole of th e herbage, some propose to be used as fodder for cattle, and the tubers as an

auxiliary to the potato and turnip in the feeding of live stock. There is abundance of room for experiments

850

on this plant.

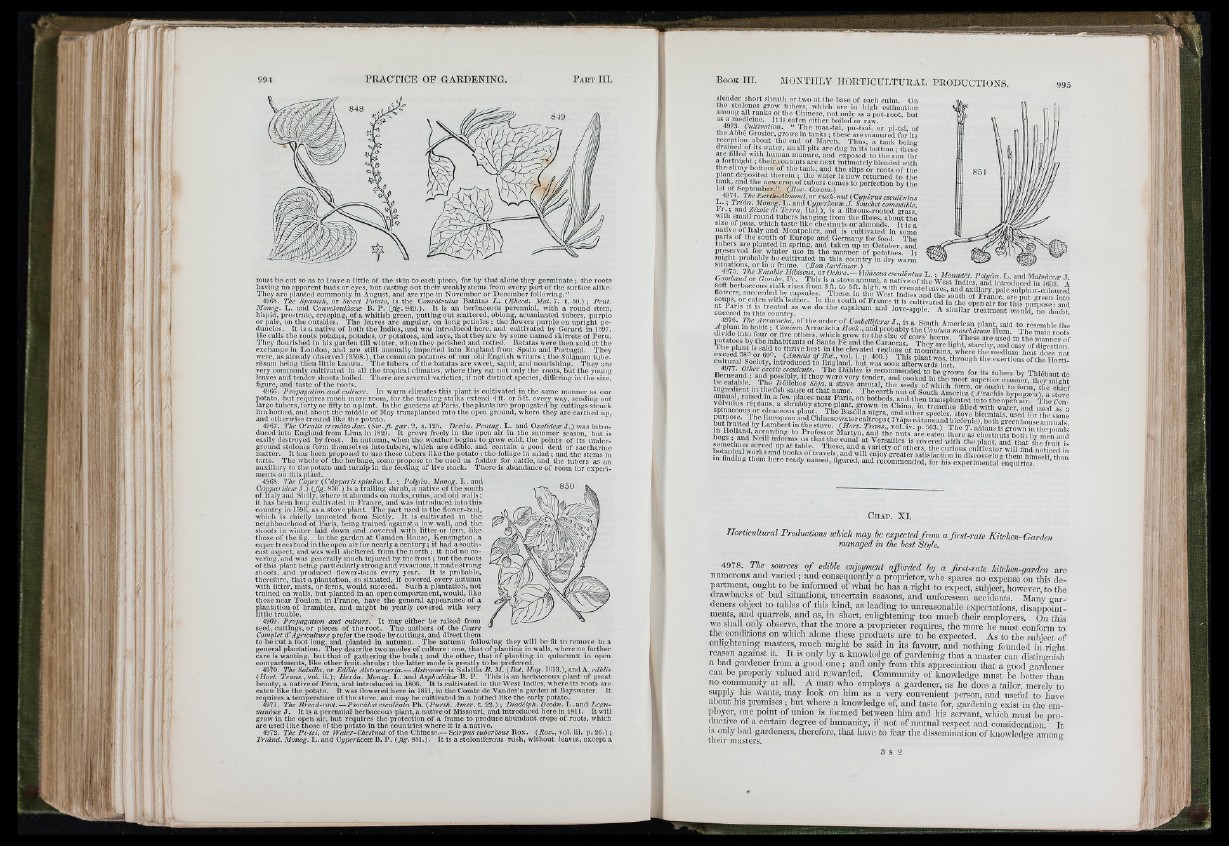

4968. The Caper {C á p p a r is sp inósa L . ; P o lyá n . Monog. L . and

Cnpparuh'cE J .) {fig. 850.) is a trailing shrub, a native of the south

of Italy and Sicily, where it abounds on rocks, ruins, and old walls :

it has been long cultivated in France, and was introduced into this

country in 1.596, as a stove plant. The part used is the flower-bud,

which is chiefly imported from Sicily. It is cultivated in th e

neighbourhood of Paris, being trained against a low wall, and the

shoots in winter laid down and covered with litte r or fern, like

those of the fig. In the gai'den a t Camden House, Kensington, a

caper trees tood in the open air for nearly a century ; it had a southeast

aspect, and was well sheltered from the north ; it had no covering,

and was generally much injured by the frost ; but the roots

of this plant being particularly strong and vivacious,it made strong

shoots, and produced flower-buds every year. It is probable,

therefore, th a t a plantation, so situated, if covered every autumn

with litter, mats, or ferns, would succeed. Such a plantation, not

trained on walls, but planted in an open compartment, would, like

those near Toulon, in France, have the general appearance of a

plantation of brambles, and might be yearly covered with very

little trouble.

4969. Pro p a g a tio n a n d cuUure. It may either be raised from

seed, cuttings, or pieces of th e root. T h e authors of the Cours

Coynplct d 'A g r icu ltu r e prefer the mode by cuttings, and direct them

to be cut a foot long, and planted in autumn. The autumn following they will be fit to remove to a

general plantation. They describe two modes of culture : one, th a t of planting in walls, where no farther

care is wanting, but th at of gathering th e buds ; and the other, that of planting in quincunx in open

compartments, I'ke other fruit-shrubs : the latter mode is greatly to be preferred.

4970. Tk e Salsilla, or E dible A lstrc eme ria.—Alstrcemèr\& Salsilla J i. M . {B o t. Mag. 1613.), and A. cdhlis

{H o rt. T ra n s ., vol. ii.); He xán. Monog. L . and Ksphodèlcce B. P . This is an herbaceous plant of great

beauty, a native of P eru, and introduced in 1806. It is cultivated in the W est Inclies, where its roots are

eaten like the potato. It was flowered here in 1811, in the Comte de Vaiides’s garden at Bayswater. It

requires a temperature of th e stove, and may be cultivated in a hotbed like the early potato.

4971. The B r ca d -ro o t— P so rà lca e sculènta Ph. {P u r sh . A m e r . t. 22.) ; Diadé lph. D e cá n . L . and I .c g u -

minòsce J . It is a perennial herbaceous plant, a native of Missouri, and introduced here in 1811. It will

grow in the open air, but requires the protection of a frame to produce abundant crops of roots, which

are used like those of the potato in the countries where it is a native.

4972. The P i- ts i, or Wate r-C h e stììu t of the Chinese.— S c trp u s tube rbsus Rox. {B o x ., vol. iii. p. 26.) ;

T r iá n d . Monog. L . and Cype ràc e si B. P . {fig . 851.). It is a stoloniferous rush, without leaves, except a

slender short sheath or two a t the base of each culm. On

the stolones grow tubers, which are in high estimation

among all ranks o fth e Chinese, not only as a pot-root, but

as a medicine. It is eaten either boiled or raw.

4973. CuUivation. “ The maa-tai, pu-tsai, or pi-tsi, of

the Abbe Grosier, grows in tanks ; these are m anured for its

reception about the end of March. Thus, a tank beinir

drained of its water, small pits arc dug in its bottom ; these

are lilled with human manure, and exposed to the sun for

a forfoight ; their contents arc next intimately blended with

th e slimy bcittom of th e tank, and th e slips or roots of the

plant deposited therein ; the water is now returned to the

tank and the new crop of tubers comes to perfection by thé

1st of September.” {B o x . Corom..)

4974. The Earth-Almond,OT rush-nut{Cypcrusesculcntus

L . ; T r ia n . Monog. L . and Cype rk c eæ J . Soucbet cotnestible,

r r . ; ana. Z izo le d i T e r ra , Ital.), is a fibrous-rooted grass

with small round tubers hanging from the fibres, about the

size of peas, which taste like chestnuts or almonds. It is a

native of Italy and Montpelier, and is cultivated in some

parts of th e south of Europe and Germany for food. The

tubers are planted in spring, and taken up in October, and

preserved for winter use in th e manner of potatoes. It

might probably be cuitivatcd in this country in dry warm

situations, or in a frame. {B o n J a rd in ie r .)

c u ltu r a l|„ cT e ,T inÆ fe d g f f e f e :

CnAr. XI,

H o rtic u ltu ra l P rod uctions w hich m ay be expected fr o m a firs t-ra te K itch e n- Garden

managed in the best Style.

4978. Th e sources o f edible enjoyment afford ed by a firs t-ra te hitchen-qarden arc

numerous and varied; and consequently a proprietor, who spares no expense on this de-

partment, ought to be informed of what he has a riglit to expect, subject, however to the

drawbacks of bad situations, uncertain seasons, and unforeseen accidents Many aar-

deners object to tables of this kind, as leading to unreasonable expectations, disappointments,

and quarrels, and as, in short, enlightening too much their employers. On this

wc shall only observe, tbat the more a proprieter requires, the more he must conform to

the conditions on which alone these products are to be expected. As to the subiect of

enlightening masters, much might be said in its favour, and nothing founded in right

reason against it. It is only by a knowledge of gardening that a master can distinguish

a bad gardener from a good one; aud only from tliis appreciation that a good gai-dener

can be properly valued and rewarded. Community of knowledge must be better tliaii

no community at all. A man who employs a gardener, as he does a tailor, merely to

supply Ins wants, may look on him as a very convenient person, and useful to have

about his premises; but where a knowledge of, and taste for, gardening exist in the employer,

one point of union is formed between him and his seiwant, which must be productive

of a certain degree of humanity, if not of mutual respect and consideration It

IS only bad gardeners, therefore, that have to fear the dissemination of knoivledge amone-

their masters. ^ ^

»! ,