kronor, distributed over 10 978 pass-books. Tbe average balance per passbook

was 196-88 kronor.

Also a number of those smaller cooperative societies which are in Sweden

called konsumtionsfôreningar have savings-funds. Their balance at

the end of 1913 was about 100 000 kronor.

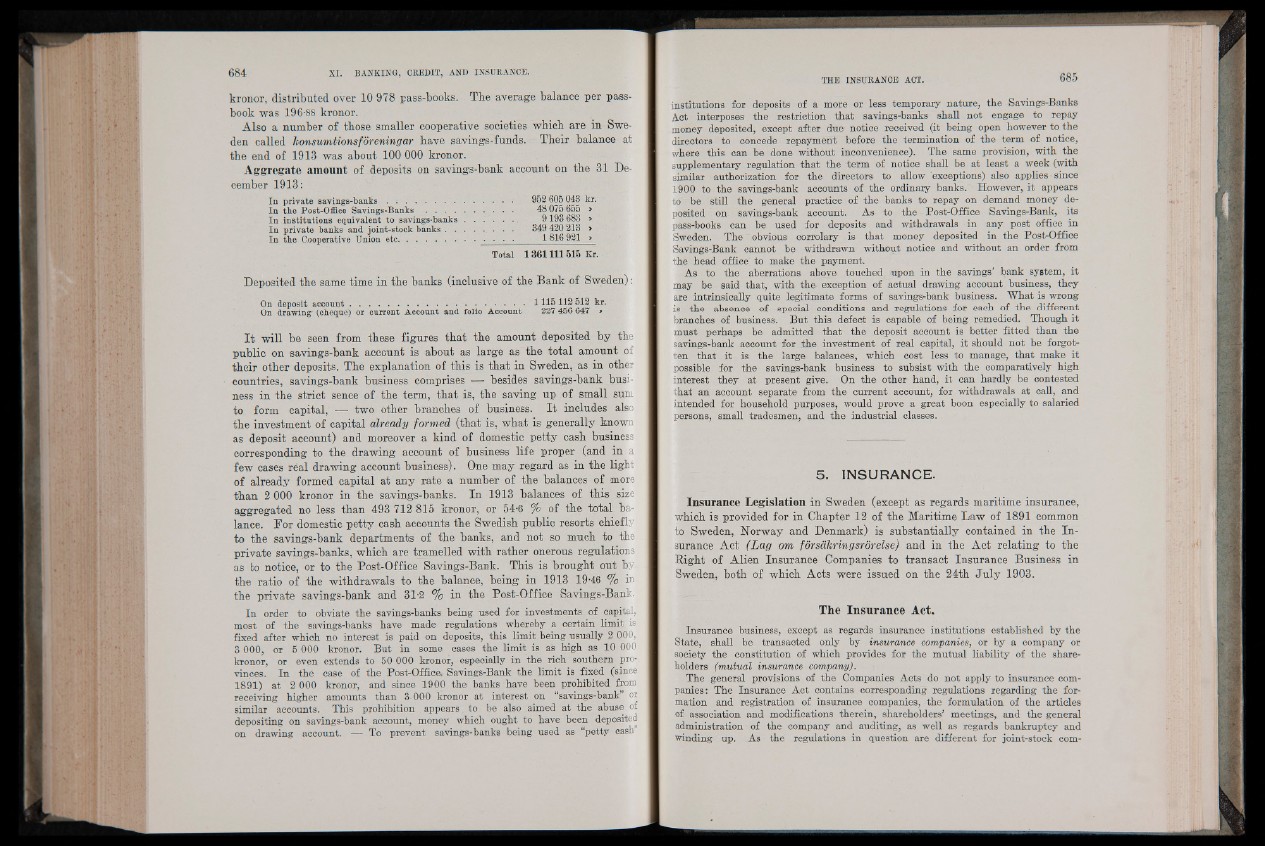

Aggregate amount of deposits on savings-bank account on the 31 December

1913:

In private savings-banks . ; 952 605 043 kr.

In tbe Post-Office Sav in g s-Ban k s.................................... 48 075 655 »

In institutions equivalent to savings-banks..................... 9193 683 »

In private banks and joint-stock banks.................... 349 420 213 >

In tbe Cooperative Union etc............... ... . .* . : ^ ^ ^46 921 >

Total 1361 111 515 Kr.

Deposited the same time in the banks (inclusive of the Bank of Sweden) :

On deposit account........................................................................1115112 512 kr.

On drawing (cbeque) or current Account and folio Account 227 456 647 >

It will be seen from these figures that the amount deposited by the

public on savings-bank account is about as large as the total amount of

their other deposits. The explanation of this is that in Sweden, as in other

countries, savings-bank business comprises — besides savings-bank business

in the strict sence of the term, that is, the saving up of small sum

to form capital, — two other branches of business. It includes also

the investment of capital already formed (that is, what is generally known

as deposit account) and moreover a kind of domestic petty cash business

corresponding to the drawing account of business life proper (and in a

few cases real drawing account business). One may regard as in the light

of already formed capital at any rate a number of the balances of more

than 2 000 kronor in the savings-banks. In 1913 balances of this size

aggregated no less than 493 712 815 kronor, or 54-6 % of the total balance.

Dor domestic petty cash accounts the Swedish public resorts chiefly

to the savings-bank departments of the banks, and not so much to the

private savings-banks, which are tramelled with rather onerous regulations

as to notice, or to the Post-Office Savings-Bank. This is brought out by-

the ratio of the withdrawals to the balance, being in 1913 19-46 % in

the private savings-bank and 31-2 % in the Post-Office Savings-Bank.

In order to obviate the savings-banks being used for investments of capital,

most of the savings-banks have made regulations whereby a certain limit is

fixed after which no interest is paid on deposits, this limit being usually 2 000,

3 000, or 5 000 kronor. But in some cases the limit is as high as 10 000

kronor, or even extends to 50 000 kronor, especially in the rich southern provinces.

In thé case of the Post-Office, Savings-Bank the limit is fixed (since

1891) at 2 000 kronor, and since 1900 the banks have been prohibited from

receiving higher amounts than 3 000 kronor at interest on “savings-bank” or

similar accounts. This prohibition appears to be also aimed at the abuse of

depositing on savings-bank account, money which ought to have been deposited

on drawing account. A- To prevent savings-banks being used as “petty cash

institutions for deposits of a more or less temporary nature, the Savings-Banks

Act interposes the restriction that savings-banks shall not engage to repay

money deposited, except after due notice received (it being open however to the

directors to concede repayment before the termination of the term of notice,

where this can be done without inconvenience). The same provision, with the

supplementary regulation that the term of notice shall be at least a week (with

similar authorization for the directors to allow exceptions) also applies - since

1900 to the savings-bank accounts of-the ordinary banks. However, it appears

to" be still the general practice of the banks to repay on demand money deposited

on savings-bank account. As to the Post-Office Savings-Bank, its

pass-books can .be used for deposits and withdrawals in any post office in

Sweden. The ~ obvious eorrolary is that money deposited in the Post-Office

Savings-Bank cannot be withdrawn without notice and without an order from

the head office to make the payment.

As -to the aberrations above touched upon in the savings’ bank system, it

may be said that, with the- exception of actual drawing account business, they

are intrinsically quite legitimate forms of savings-bank business. What is wrong

is the absence of special conditions and regulations for each of the different

branches of business. But this defect is capable of being remedied. Though it

must perhaps be admitted that the deposit account is better fitted than the

savings-bank account for the investment of real capital, it should not be forgotten

that it is the large balances, which cost less to manage, that make it

possible for the savings-bank business to subsist with the comparatively high

interest they at present give. On the other hand, it can hardly be contested

that an account separate from the current account, for withdrawals at call, and

intended for household purposes, would prove a great boon especially to salaried

persons, small tradesmen, and the industrial classes.

5. INSURANCE.

Insurance Legislation in Sweden (except as regards maritime insurance,

which is provided for in Chapter 12 of the Maritime Law of 1891 common

to Sweden, Norway and Denmark) is substantially contained in the In surance

Act (Lag om fôrsakringsrôrelse) and in the Act relating to the

Right of Alien Insurance Companies to transact Insurance Business in

Sweden, both of which Acts were issued on the 24th July 1903.

The Insurance Act.

Insurance business, except as regards insurance institutions established by the

State, shall be transacted only by insurance companies, or by a company or

society the constitution of which provides for the mutual liability of the shareholders

(mutual insurance company).

The general provisions of the Companies Acts do not apply to insurance companies:

The Insurance Act contains corresponding regulations regarding the formation

and registration of insurance companies, the formulation of the articles

of association and modifications therein, shareholders’ meetings, and the general

administration of the company and auditing, as well as regards bankruptcy and

winding up. As the regulations in question are different for joint-stock com