waterfall at a small rental and for a long period of time, which contract

was only to come into force in case the Crown was awarded the proprietary

rights. In this manner the present proprietor would _be secured in the

right to use the water-power for a considerable time to come, even if the

finding of the court went against him. However, in actual practice these

“waterfall rights” have not hitherto been made use of, the reason apparently

being the novelty of the legal form, and the fact that lenders prefer

to take an ordinary mortgage on real property.

One way o f encouraging the conveyance of waterfalls with such rights

would be, obviously, that the State itself should step forward as a lender.

In fact, in the Riksdag of 1912 a bill was introduced to investigate the

question of the creation of a loan fund for users of State waterfalls with

waterfall rights, and the Riksdag passed the bill. In the fo llow in g year,

a supplementary bill was brought forward proposing that the investigation

thus called for might likewise be extended to a loan fund for the users

of waterfalls in private hands.

In conclusion, as a step in the waterfall policy- of the State, it may be

pointed out that the Crown has purchased several large waterfalls from

private persons and concerns, partly in order to hold them in reserve for

a future electrification of the State railways, partly in order to complete

its property in certain river areas. Among the latter purchases are to be

noted those in virtue of which the State has acquired practically sole

ownership of all the water-power in the River Gota alv between Lake

Vanern and the Sea.

But the State can and should encourage the utilization of water-power

even in other ways than those just indicated, namely by framing its legislation

in such a spirit that the least possible obstacles shall be encountered

and the greatest possible promptitude effected in the legal treatment

of questions relating to the construction of power works and dams. In

this respect much remains to be done.

True, Sweden posses a Water Act of such a recent date as the Royal

Ordinance “ concerning the landowner’s right to the water on his land”, of

December 30, 1880, supplemented by Royal Proclamation of October 20,

1899 “ concerning regulations to be observed by those desirous of acquiring

a license from the King to build on a Crown water-course (kungsadra1) ”.

But the regulations of that act do not by any means satisfy the legitimate

demands of the modern water-power industry. Not only is the legal and

administrative procedure far too cumbrous and slow and leaves too little

scope for expert knowledge, but the law actually place's obstacles in the

way of a rational utilization of water power, and in many cases renders

it impossible. In the last respect it is specially to be noted that the law

does not concede the right of expropriating ground for the actual power

1 The purpose and definition of the term “K.ungs&dra” (“Kings artery”) will he found in

the second section of paragraph 7 of the said Royal Proclamation. Cf. also the article on

Fishing.

station, and that it does not provide facilities for a water-power user to

effectuate the regulation of a lake or the damming up of water, supposing

damage thereby to be caused to a building, waterfall, or the like, belonging

to another, no matter how great the public benefit accuring from the

enterprise. On the other hand, by the Electric Installations Act of June

27, 1902, the water power industry has been tolerably well provided for,

with reference to the right to carry over another ground the electric power

lines often imperatively necessary for modern power works.

A revision of the Water Act was set on foot in 1906, when the Government

appointed a committee to draft proposals for new legislation

with regard to a landowner’s rights over the water in his ground. That

committee, jointly with another committee of same year appointed to draw

up proposals for amendments in the law relating to the drainage of ground,

brought forward on the December 17, 1910, a scheme for an amended

Water Act. This extensive scheme, which contains many new and remarkable

suggestions, is at present being considered by the authorities. Furthermore,

of late a scheme for a new floating law, as well as a new bill providing

for greater security with regard to agreements for delivery of electrical

energy, etc,, have been worked out. It is to be hoped that the Riksdag

will soon see its way to decide this very important question, and that the

new law will be framed in such a spirit that it will not impede, but facilitate

and encourage the speedy and scientific exploitation of Sweden’s

water power.

The formal stumbling-blocks once removed, there is no doubt whatever

that the people of Sweden will contrive, within a not too far distant future,

to turn to account the national wealth which lies in her magnificent supplies

of water-power, and which, utilized in the right way, should give her

an extremeley favourable position in the competition going on between

the nations.

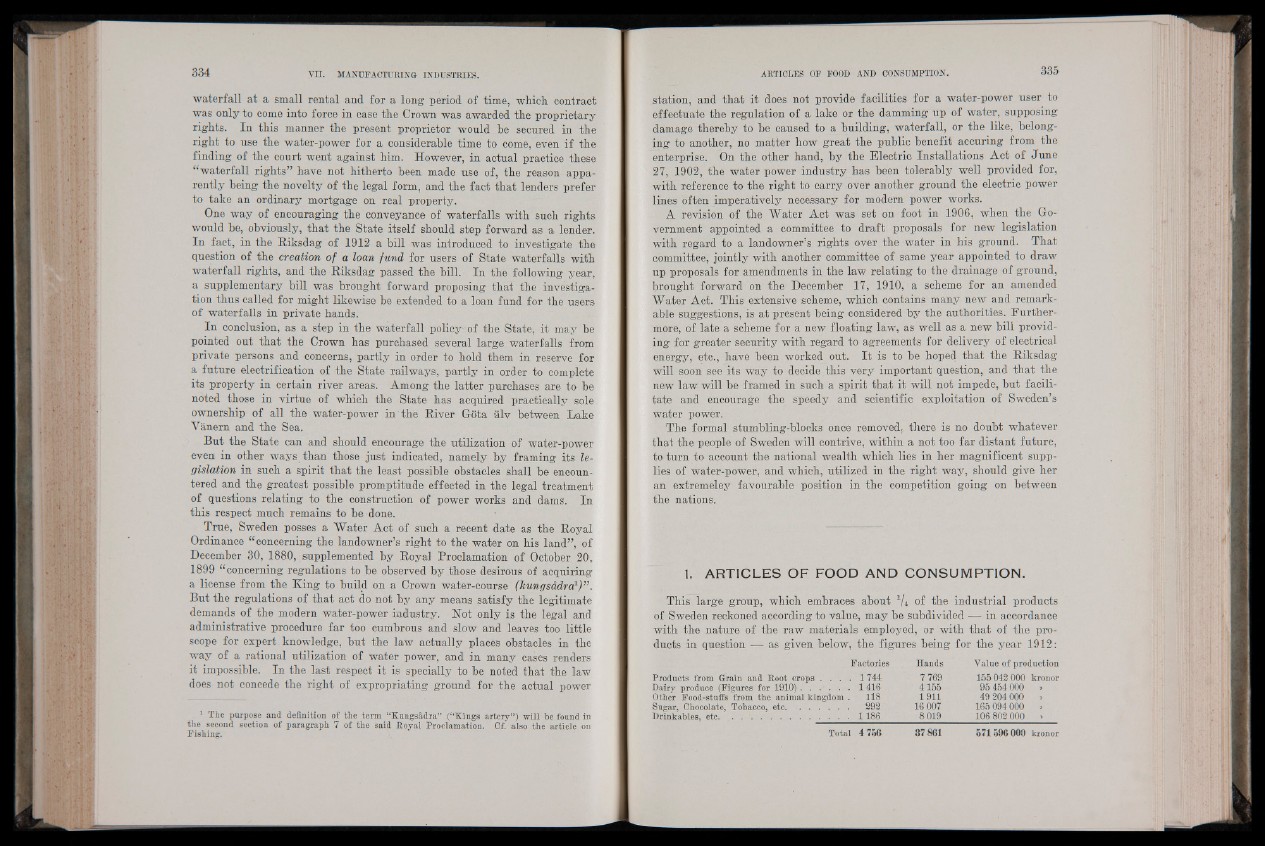

1. ARTICLES OF FOOD AND CONSUMPTION.

This large group, which embraces about 1/4 of the industrial products

of Sweden reckoned according to value, may be subdivided — in accordance

with the nature of the raw materials employed, or with that of the products

in question — as given below, the figures being for the year 1912:

Factories Hands Value of production

Products from Grain and Root crops . . . . 1744 7 769 155 042 000 kronor

Dairy produce (Figures for 1910) . . . . . . 1 416 4155 95 454 000 >

Other Food-stuffs from the animal kingdom . 118 1911 49 204 000 >

Sugar, Chocolate, Tobacco, e t c . 292 16 007 165 094 000 >

Drinkables, e t c . ................................................ 1186 8 0i9 106 802 000 >

Total 4 756 37 861 571596 000 kronor