The value of Swedish Water-Power. It would seem to be a very delicate

matter to estimate aright the value represented by Swedish water-power. However,

in “Sveriges Nationalformogenhet” an attempt has been made. In this

preliminary estimate the basis for calculation has been partly the prices actually

paid on the sale of certain waterfalls, partly statements as to the profit

made by certain water-power enterprises which may be assumed to have come

into normal working order. The results yielded by this estimate are a capital

value for the north of Sweden of, on an average, 75 kronor, and for the south

of Sweden of, on an average, 90 kronor per turbine horse-power for the waterfalls

which in 1908 had been equipped or were in process of equipment. Further,

the estimate has been extended to the corresponding value of the water7

falls which it may be assumed will be equipped in the course of the next fifty

years, distributed in different groups, and this value has been reduced to the

year 1908 at Q% interest for private enterprises and 4'e % for State enterprises.

The outcome of this preliminary computation is that Sweden’s water-power

“fit to be equipped” may be assumed to represent in 1908 a total value, of

138‘6 million kronor, out of which 21 % fall to State enterprises, and 7 9 ^ to

private enterprises.

This figure is surprisingly low. But, in the first place, the rate at which

the utilization of water-power is assumed to take place during the term of 50

years in question seems to have been rather cautiously estimated, since the basis

of calculation has been that 3 million horse-power would be equipped during

this period of fifty years, that is, on an average, 60 000 horse-power per: annum,

or about the same amount of power as was added in each of the years

1912 and 1913. However, as far as can be judged at present, the immediate

The Porjus Falls.

P h o to . L . We s t f e l t , P o rju s .

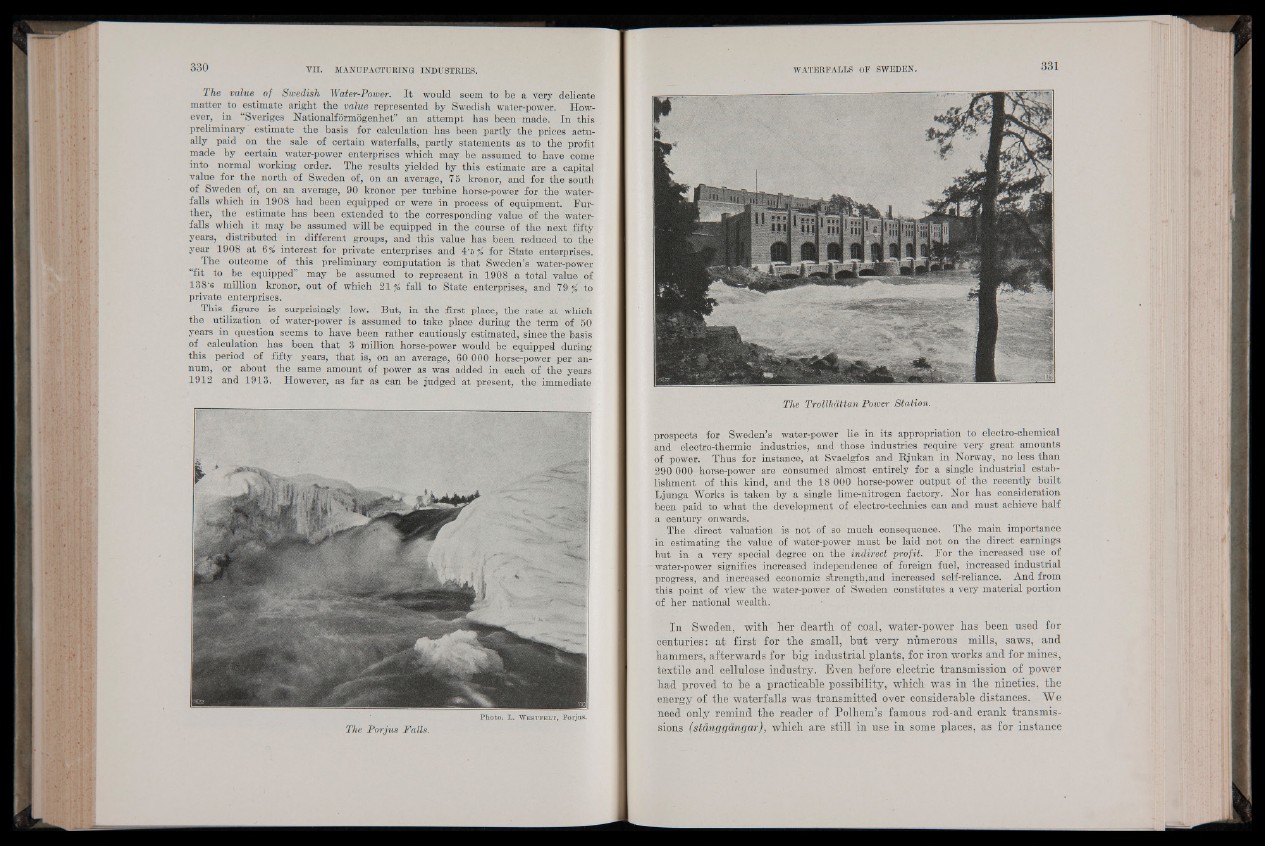

The Trollhättan Power Station.

prospects for Sweden’s water-power lie in its appropriation to electro-chemical

and electro-thermic industries, and those industries require very great amounts

of power. Thus for instance, at Svaelgfos and Bjukan in Norway, no less than

290 000 horse-power are consumed almost entirely for a single industrial establishment

of this kind, and the 18 000 horse-power output of the recently built

Ljunga Works is taken by a single lime-nitrogen factory. Nor has consideration

been paid to what the development of electro-technics can and must achieve half

a century onwards.

The direct valuation is not of so much consequence. The main importance

in estimating the value of water-power must be laid not on the direct earnings

but in a very special degree on the indirect profit. For the increased use of

water-power signifies increased independence of foreign fuel, increased industrial

progress, and increased economic strength,and increased self-reliance. And from

this point of view the water-power of Sweden constitutes a very material portion

of her national wealth.

In Sweden, with her dearth of coal, water-power has been used for

centuries: at first for the small, but very numerous mills, saws, and

hammers, afterwards for big industrial plants, for iron works and for mines,

textile and cellulose industry. Even before electric transmission of power

had proved to be a practicable possibility, which was in the nineties, the

energy of the waterfalls was transmitted over considerable distances. We

need only remind the reader of Polhem’s famous rod-and crank transmissions

(stanggangar), which are still in use in some places, as for instance