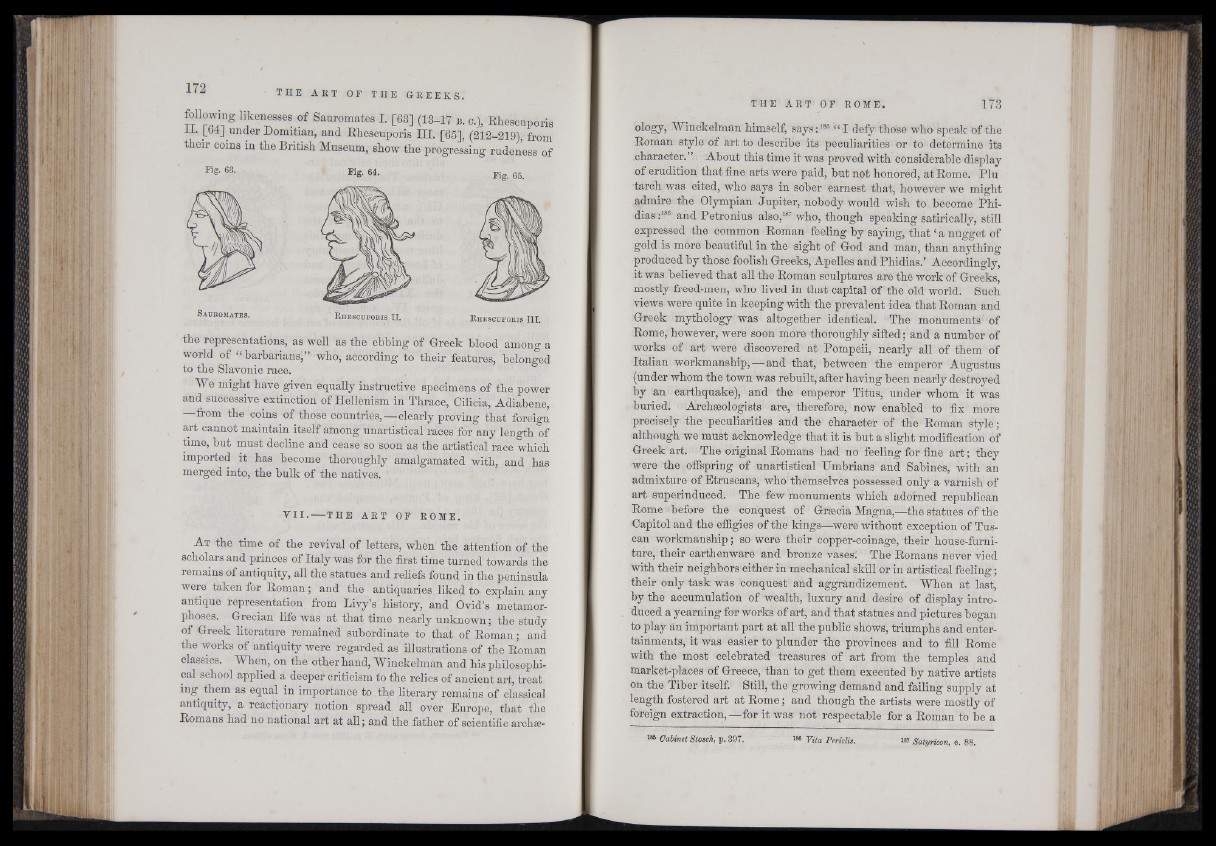

foliowing likenesses of Sauromates I. [63] (13-17 b. c.), Rhescuporis

U. [64] under Domitian, and Rhescuporis III. [65], (212-219) from

their coins in the British Museum, show the progressing rudeness of

K e - 63- Kg. 64. Fig. 65

S a u r om a t e s . R h e s c u p o r is I I . . R h e s c u p o r is I I L

the representations, as well as the ebbing of Greek blood among a

world of “ harhariansj” who, according to their features, belonged

to the Slavonic race.

We might have given equally instructive specimens of the power

and successive extinction of Hellenism in Thrace, Cilicia, Adiabene,

from the coins of those countries, — clearly proving that foreign

art cannot maintain itself among unartistical races for any length of

time, hut must decline and cease so soon as the artistical race which

imported it has become thoroughly amalgamated with, and has

merged into, the hulk of the natives. '

V I I . — THE ART OF ROME.

A t the time of the revival of letters, when the attention of the

scholars and princes of Italy was for the first time turned towards the

remains of antiquity, all the statues and reliefs found in the peninsula

were tkken for Roman ; and the antiquaries liked to explain any

antique representation from Livy’s history, and Ovid’s metamorphoses.

Grecian life was at that time nearly unknown; the study

of Greek literature remained subordinate to that of Roman ; and

the works of antiquity were regarded as illustrations of the Roman

classics. When, on the other hand, Winckelman and his philosophical

school applied a deeper criticism to the relics of ancient art, treat

ing^ them as equal in importance to th,e literary remains of classical

antiquity, a reactionary notion spread all over Europe, that the

Romans had no national art at all ; and the father of scientific archæol°

gy, Winckelman himself, says:185 “ I defy those who speak of the

Roman style of art to describe its peculiarities or to determine its

character.”:: About this time it was proved with considerable display

of erudition that fine arts were paid, but not honored, at Rome. Plu

tarch was cited, who says in sober earnest that, however we might

admire the Olympian Jupiter, nobody would wish to become Phidias:

186 and Petronius also,187 who, though speaking satirically, still

expressed the common Roman feeling by saying, that ‘ a nugget of

gold is more beautiful in the sight of God and man, than anything

produced by those foolish Greeks, Apelles and Phidias.’ Accordingly,

it was believed that all the Roman sculptures are the work of Greeks,

mostly freed-men, who lived in that capital of the old world. Such

views were quite in keeping with the prevalent idea that Roman and

Greek mythology was altogether identical. The monuments of

Rome, however, were soon more thoroughly sifted; and a number of

works of art were discovered at Pompeii; nearly all of them of

Italian workmanship,—and that, between the emperor Augustus

(under whom the town was rebuilt, after having been nearly destroyed

by an earthquake), and the emperor Titus, under whom it was

buried. Archaeologists are, therefore, now enabled to fix more

precisely the peculiarities and the character of the Roman style;

although we must acknowledge that it is hut a slight modification of

Greek art. The original Romans had no feeling for fine art; they

were the offspring of unartistical Umbrians and Sabines, with an

admixture of Etruscans, who themselves possessed only a varnish of

art superinduced; The few monuments which adorned republican

Rome before the conquest of Grsecia Magna,—the statues of the

Capitol and the effigies of the kings—were without exception of Tuscan

workmanship ; so were their copper-coinage, their house-furni-

ture, their earthenware and bronze vases: The Romans never vied

with their neighbors either in mechanical skill or in artistical feeling;

their only task was conquest and aggrandizement. When at last,

by the accumulation of wealth, luxury and desire of display introduced

a yearning for works of art, and that statues and pictures began

to play an important part at all the public shows, triumphs and entertainments,

it was easier to plunder the provinces and to fill Rome

with the most celebrated treasures of art from the temples and

market-places of Greece, than to get them executed by native artists

on the Tiber itself.1 Still, the growing demand and failing supply at

length fostered art at Rome; and though the artists were mostly of

foreign extraction,—for it was not respectable for a Roman to he a

185 Cabinet Stosch, p. 397. 186 Vita Periclis. 18T Satyricon, c. 88.