sculptor —Roman nationality impressed its stamp on the coins and

gems, reliefs and statues, marbles and bronzes, of the time of the

Emperors. The principal features of Roman art are a somewhat

ponderous dignity,' and a want of poetical inspiration, but withal a

close imitation of native, national truthfulness, and great regard for

individuality; without that Greek freshness, freedom and harmony

which rou^g in the beholder the consciousness of the divine nature

of our soul. The composition of the Roman works of art is heavy

the execution often over-polished and empty. Whilst the Greek

artist selected his subjects from mythology, the Roman liked to represent

sacrifices, triumphal processions, military marches, battles,

and “ allocutions, ’ marriage-feasts and other scenes of domestic life.

The Greek idealized'the features of great men; the Roman did not

ennoble the ugliness of old Tiberius, the idiocy of Domitian and

the ferocious looks of Commodus and Caracalla. The Greek made

scarcely any distinction, in sculpture, between the Greek and the

barbarian—the same idealism surrounds them both, and assimilates

them to one another; the Roman artist made a eharacteristical difference

between enemies of Rome and the civis Romanus. Still, at the

time of the Emperors, the Roman type itself had ceased to be constant

Citizenship having been extended to half a world, barbarians

constituted the bulk of the army, and their equally-barbarian officers

were raised first into the Senate, then to the imperial throne. Accordin

g ly ,^ artists of Rome gave, on the whole, less importance to the

type than to the costume of the foreign hostile nations, by which

alone they differed from the mongrel Romans, who then represented

a cosmopolitan amalgam of all the white races. On the great

cameos of the time of Augustus and Tiberius, at Vienna and Paris

(which, by their dramatic and picturesque composition of the groups

materially differ from Greek reliefs), the Pannonian and Vindelician

prisoners have no individual features; nor is the statue of the “ river

Jordan” on the triumphal arch of the emperor Titus characterized

by a Shemitic physiognomy; but, on the column and arch of Traian

which contains the best of all the Roman works of art, we easily

recognise the Dacian, [70] whose features are perpetuated in the Wal-

lachian of our days. In the dying gladiator of the Capitol, and on

the sarcophagus of the Vigna Ammendola,1® we see the Celtic Gaul

® ^Presented; and Mr. Gottling recognises an ancient German

Rome11 a prisoner which adorned a triumphal arch at

After the eclectic idealism prevalent under the reign of the

Emperor Hadrian, we no longer find any endeavor to fix the

188 Monummti Intditi delV Imlituto Archeologka di Roma, 1, Pi"

national peculiarities of foreign nations on monuments of art. The

Teutonic Markomans on the columns of Antoninus, the Turanian

Parthians on the arch of Septimus Severus, differ only by their costume

from Dacians, and from the Roman soldiers who fight against

them; and we must admit that the pharaonic Egyptian artists

remained unsurpassed, even by Greeks and Romans, in the accuracy

with which they observed and rendered the national lype of all the

tribes with which they happened to come into contact. The Assyrians

and Persians were second in this respect to the Egyptians; still

they were, on the whole, faithful enough, whereas with the Greeks any

national peculiarity merged in the glorification of the human form:

accordingly, Egyptians and Asiatics are by them drawn and sculptured

with Hellenic features. The Roman is by far more truthful,

but his art is short-lived. Before Augustus it is either Etruscan or

Greek; after Septimus Severus it loses its national character, and

step by step transforms itself into the Byzantine Christian. Two

centuries carry us from the beginning of Roman art to its decay;

its full bloom lasted only just for the score of years which embraces

the reign of the emperor Trajan, since under Hadrian it lost its

)Roman features, and was swamped by an elegant and refined imitation

of every style of art. About the same time that the imperial

throne fell into the hands of Asiatic Syrians, of Africans, Arabs, and

northern barbarians, Roman art became barbarous, and revived'only

when, about the time of Justinian and his successors, a new nationality,—

the Graeco-Byzantine— consolidated and crystallized itself

under the influences of Christianity out of the mixture of all the

races in the Roman empire.

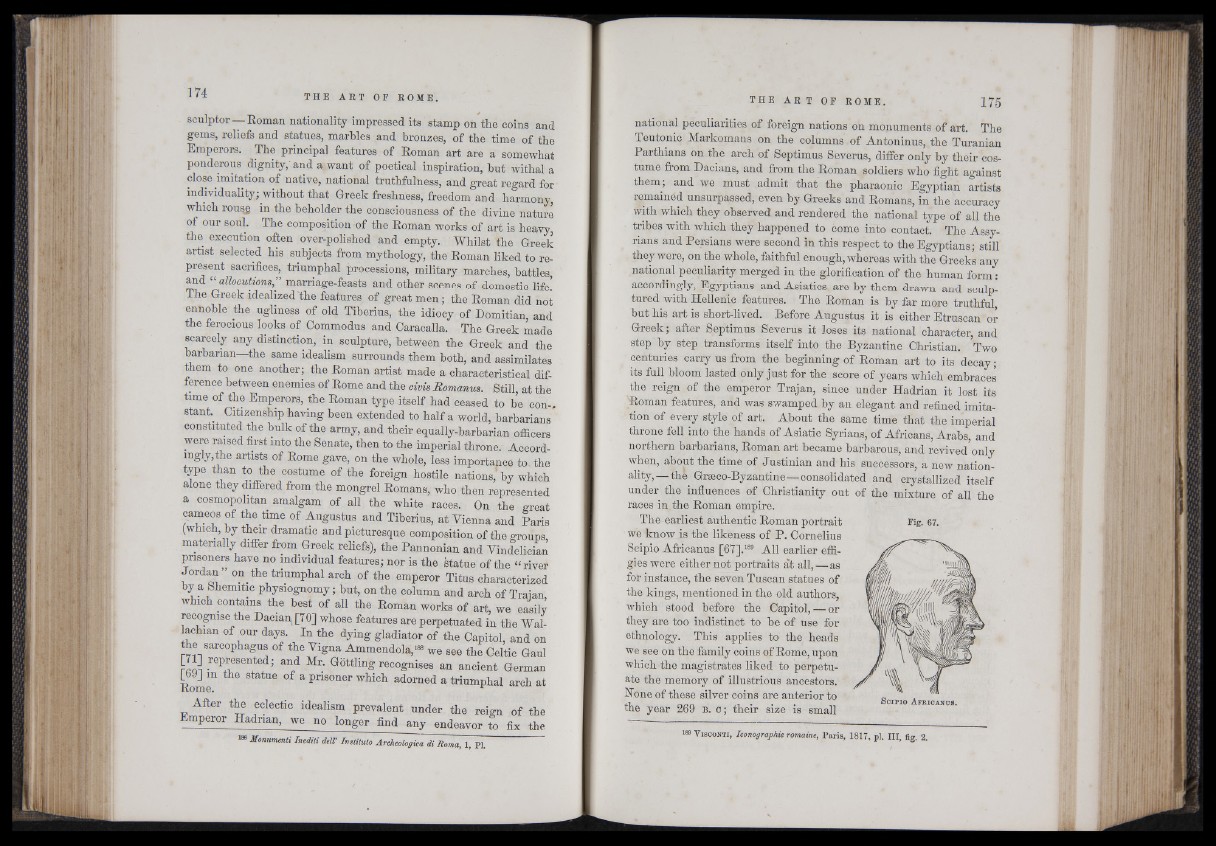

The earliest authentic Roman portrait Fig. 67.

we know is the likeness of P. Cornelius

Scipio Africanus [67].189 All earlier effigies

were either not portraits at all,—as

for instance, the seven Tuscan statues of

the kings, mentioned in the old authors,

which stood before the Capitol, — or

they are too indistinct to be of use for

ethnology. This applies to the heads

we see on the family coins of Rome, upon

which the magistrates liked to perpetuate

the memory of illustrious ancestors.

Hone of these silver coins are anterior to D x r . . . I S c i i i o A f r ic a n u s . tne year 269 b . c ; their size is small

189 Visconti, Iconographie romaine, Paris, 1817, pl. Ill, fig. 2.