style, has failed to reproduce the harmonious delicacy of the originals.

They can he consulted in the Denkmäler.71

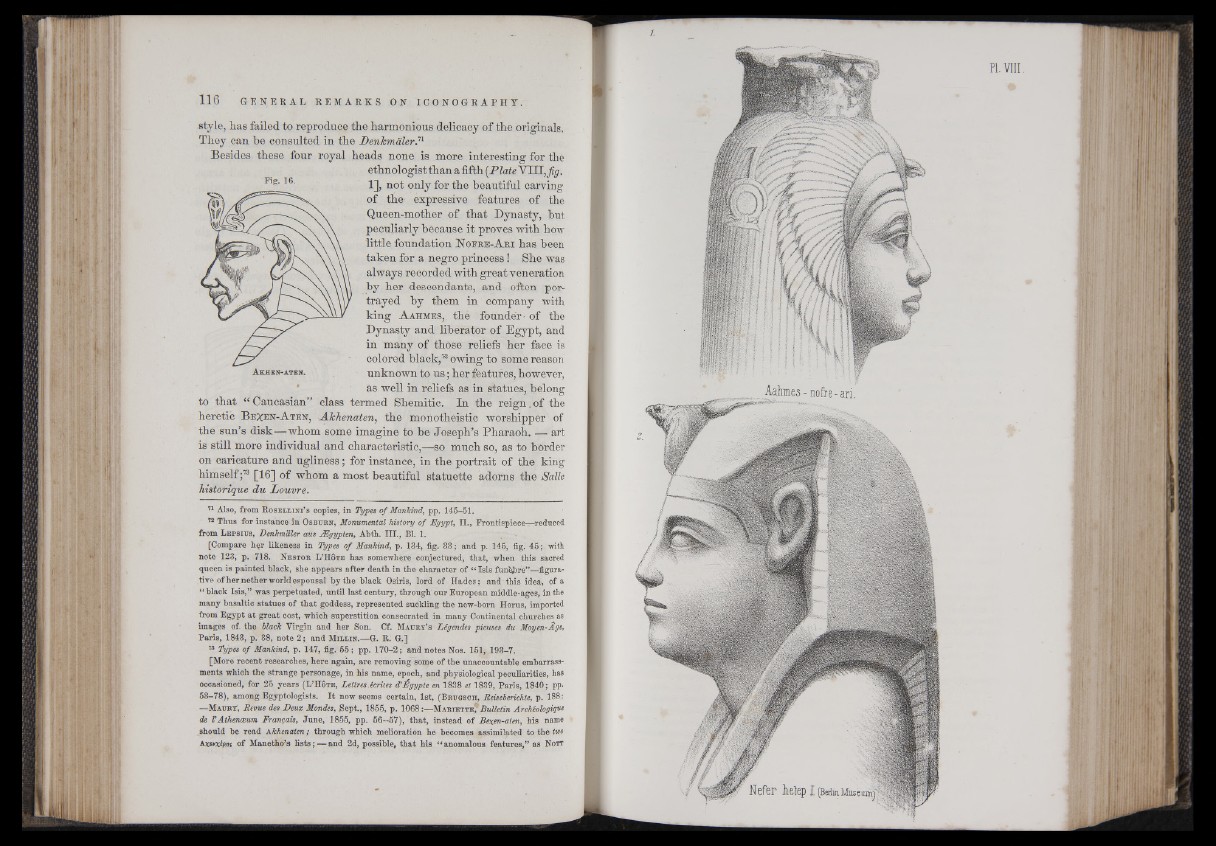

Besides these four royal heads none is more interesting for the

ethnologist than a fifth (Plate ~\iA±,fig.

1], not only for the beautiful carving

of the- expressive features of the

Queen-mother of that Dynasty, hut

peculiarly because it proves with how

little foundation Noere-Ari has been

taken for a negro princess ! She was

always recorded with great veneration

by her descendants, and often portrayed

by them in company with

king Aahmès, the founder - of the

Dynasty and liberator of Egypt, and

in many of those reliefs her face is

colored black,78 owing to some reason

Fig. 16.

A k h e n -a ten . unknown to us ; her features, however,

as well in reliefs as in statues, belong

to that “ Caucasian” class termed Shemitie. In the re ign. of the

heretic Bexen-Aten, Akhenaten, the monotheistic worshipper of

the sun’s disk—whom some imagine to be Joseph’s Pharaoh. — art

is still more individual and characteristic,—so much so, as to border

on caricature and ugliness ; for instance, in the portrait of the king

himself ;73 [16] of whom a most beautiful statuette adorns the Salle

historique du Louvre.

71 Also, from R o s e l l i n i ’s copies, in Types of Mankind, pp. 145-51.

72 Thus for instance in O s b u r n , Monumental history of Egypt, II., Frontispiece—reduced

from L e p s iu s , Denkmäler aus Ægypten, Abth. III., Bl. 1.

[Compare hçr likeness in Types of Mankind, p. 134, fig. 33 ; and p. 145, fig. 45 ; | with

note 123, p. 718. N e s t o r L ’H ô t e has somewhere conjectured, that, when this sacred

queen is painted black, she appears after death in the character of “ Isis funèbre”—figurative

of her nether world espousal by the black Osiris, lord of Hades; and this idea, of a

“ black Isis,” was perpetuated, until last century, through our European middle-ages, in the

many basaltic statues of that goddess, represented suckling the new-born Horus, imported

from Egypt at great cost, which superstition consecrated in many Continental churches as

images of. the black Virgin and her Son. Cf. M a u r y ’s Légendes pieuses du Moyen-Âge,

Paris, 1843, p. 38, note 2; and M i l l i n .—G. R. G.]

73 Types of Mankind, p. 147, fig. 55; pp. 170-2; and notes Nos. 151, 193-7.

[More recent researches, here again, are removing some of the unaccountable embarrassments

which the strange personage, in his name, epoch, and physiological peculiarities, has

occasioned, for 25 years (L ’H ô t e , Lettres .écrites d'Êgypte en 1838 et 1839, Paris, 1840; pp*

53-78), among Egyptologists. It now seems certain, 1st, ( B r u g s c h , Reiseberichte, p. 188:

—Maury', Revue des Deux Mondes, Sept., 1855, p. 1068 :—M a r ie t t e ? 1 Bulletin Archéologique

de VAthenoeum Français, June, 1855, pp. 56—57), that, instead of Bexen-aten, his name

should be read Akhenaten ; through which melioration he becomes assimilated to the two

hxfivxlpK of Manetho’s lists; — and 2d, possible, that his “ anomalous features,” as N o t t

Pl. VIII

Aahmes-nofre-ari.