and acuminated ; tlie palatine arch, level ; the fissure in the floor of

the orbit very large.”

Turning our hacks upon the Frozen Ocean, and tracing to their

sources the three great rivers—the Obi, Yennisei, and Lena—which

drain the slopes of Northern Asia, we gradually exchange the region

of tundras and barren plains, for elevated steppes or table-lands, the

region of the reindeer and dog for that of the horse and sheep, the

region whose history is an utter blank for one which has witnessed

such extensive commotions and displacements of the great nomadic

races, who, probably, in unrecorded times, dwelt upon the central

plateaux of Asia, before these had lost their insular character. Travelling

thus southward, we further remark that a globular conformat!°

n the human sku11 replaces the long, narrow, pyramidal type of

the North. , - - :

In our attempt to exhibit a general view of the cranial forms or

types of Central Asia, I deem it best to direct attention to the region

of country which gives origin to the Yennisei,'about Lake Baikal,

and m the Greater Altai chain, south of the TTriangchai or Southern

bamoiedes. For we here encounter, in the Kalkas and Mongolians

proper of the desert of Shamo, a type of head which is distinct from

that of the Hyperboreans, and to which the other great nomadic races

are related, m a greater or less degree. I have selected, as the most

fitting representative of this Asiatic type or form, the cranium of a

Kalmuck .(Ho. 1553 of the Mortonian Collection), sent to the Aca-

^ A.MEE> H S t Petersburg, shortly after the decease of

‘ Norton. This skull is chosen as a standard for reference on

account of the “ extent to which the Mongolian physiognomy is’the

type and sample of one of the most remarkable divisions of the

human race.”138 ; Moreover, the Mongols possess the physical chap

t e r s of their race m the most eminent degree,139 they are the most

decidedly nomadic, and their history, under the guidance, of Tchengiz-

Khan and his immediate successors, constitutes a highly-important

chapter m the history of the world ; and, finally, because they occupy

the centre of a well-characterized and peculiar'floral and fauna! region,

extending from Japan on the east to the Caspian on the west

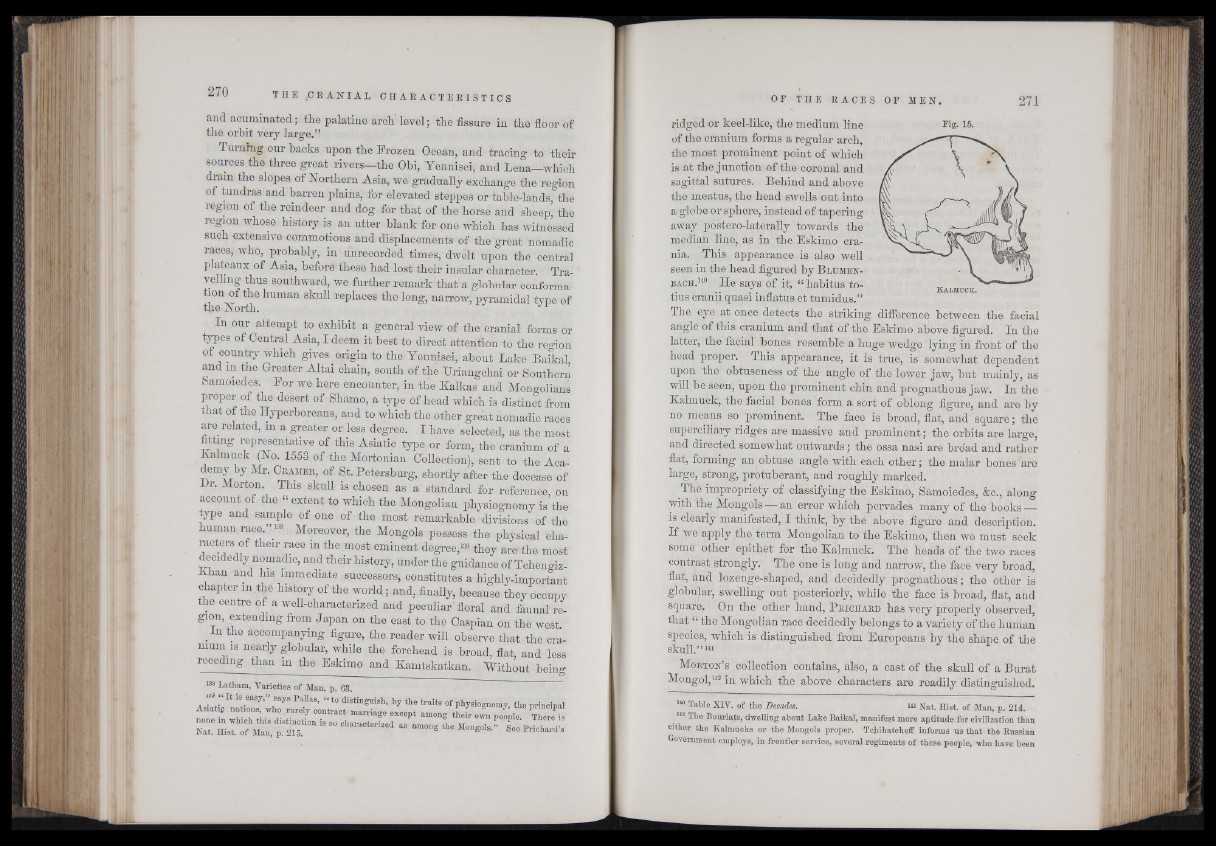

In the accompanying figure, the reader will observe that thé cra-

mum is nearly globular, while the forehead is broad, flat, and less

receding than m the Eskimo and Kamtskatkan. Without being

138 Latham, Varieties of Man, p. 63.

^ “ It is easy,” says Pallas, “ to distinguish, by the traits of physiognomy, the principal

Asiatip nations who rarely contact marriage except among their oZ p o o l H I is

Nat^ Hist I i l l M S 18 S° °ha“ Zed “ am°“S g See Prichard's

ridged or keel-like, the medium line Fig-15.

of the cranium forms a regular arch,

the most prominent point of which

is at the junction of the coronal and

sagittal sutures. Behind and above

the meatus, the head swells out into

a globe or sphere, instead of tapering

away poStero-laterally towards the

median line, as in the Eskimo crania.

This appearance .is also well

seen in the head figured by B ltjmen-

bach.140 He says of it, “ habitus to-

tius Cranii quasi inflatus et tumidus.”

The eye at once detects the striking difference between the facial

angle of this cranium and that of the Eskimo above figured. In the

latter, the facial bones resemble a huge wedge lying in front of the

head proper. This appearance, it is true, is somewhat dependent

upon the obtuseness of thé angle of the lower jaw, but mainly, as

will be seen, upon the prominent chin and prognathous jaw. In the

Kalmuck, the facial bones form a sort of oblong figure, and are by

no means so prominent. The face is broad, flat, and square ; the

superciliary ridges are massive and prominent; the orbits are large,

and directed somewhat outwards ; the ossa nasi are broad and rather

flat, forming an obtuse angle with each other ; the malar bones are

large, strong, protuberant, and roughly marked.

The impropriety of classifying the Eskimo, Samoiedes, &c., along

ydth the Mongols — an error which pervades many of the books —

is clearly manifested, I think, by the above figure and description.

If we apply the term Mongolian to the Eskimo, then we must seek

some other epithet for the Kalmuck. The heads of the two races

contrast, strongly. The one is long and narrow, the face very broad,

flat, and lozenge-shaped, and decidedly prognathous; the other is

globular, swelling out . posteriorly, while the face is broad, flat, and

square. On the other hand, P richard has very properly observed,

that “ the Mongolian race decidedly belongs to a variety of the human

species, which is distinguished from Europeans by the shape of the

skull.” 141

M orton’s collection contains, also, a cast of the skull of a Burat

Mongol,142 in which the above characters are readily distinguished.

140 Table XIV. of the Decades. w Nat. Hist, of Man, p. 214.

142 The Bouriats, dwelling about Lake Baikal, manifest more aptitude for civilization than

either the Kalmucks or the Mongols proper. Tcjiihatcheff informs us that the Russian

Government employs, in frontier service, several regiments of these people, who have been