tional types of the inhabitants of the Persian empire; as we see

plainly on the reliefs of the tomb of king Darius Hystaspes, which

he had excavated in the mountain Eachmend, near Persepolis. The

king is represented here in royal attire before the fire-altar, over

which hovers his guardian angel, in the form of a human half-figure

rising from a winged disc. This group, grand in its simplicity, is

placed on a beautifully decorated platform, supported by two rows

of Caryatides, sixteen in each row, representing the four different

nationalities subject to this king,-,—besides the ruling Persians, who

occupy a more distinguished position, flanking the composition on

both sides, and typified by three spearsmen of the royal guard, and

by three courtiers who raise their hands in adoration.

This relief of the sepulchre of Darius in Persia, is one of the most

valuable documents of ethnology, second in importance only to king

M e n e ph t h a h s (S e t i I.) celebrated tomb at Thebes recording four

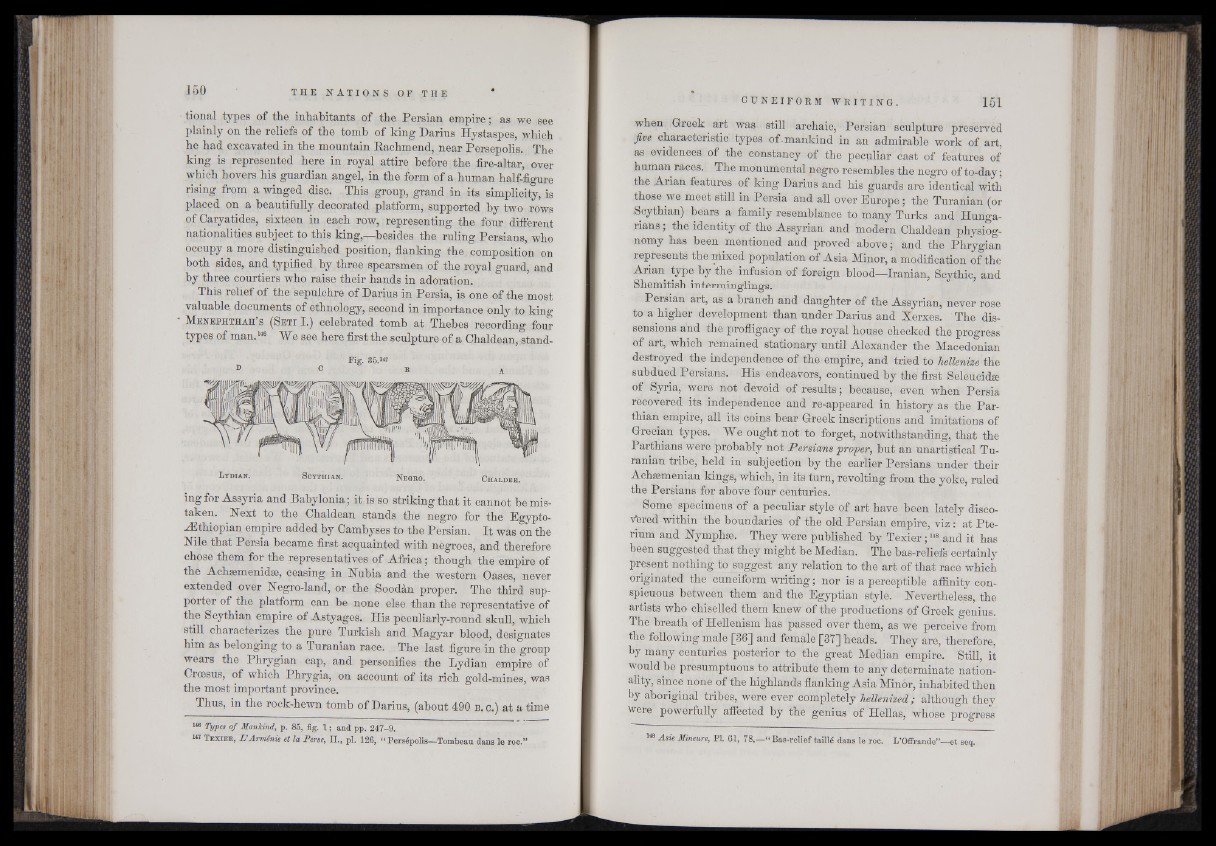

types of man.146 We see here first the sculpture of a Chaldean, stand-

Fig. 85A« n c B a

Lydian. Scythian. Negeo. Chaldee.

ing for Assyria and Babylonia; it is so striking that it cannot be mistaken.

A ext to the Chaldean stands the negro for the Egypto-

.Æthiopian empire added by Cambyses to the Persian. It was on the

Nile that Persia became first acquainted with negroes, and therefore

chose them for the representatives of Africa ; though the empire of

the Achæmenidæ, ceasing in Nubia and the western Oases, never

extended over Negro-land, or the Soodàn proper. The third supporter

of the platform can be none else than the representative of

the Scythian empire of Astyages. His peculiarly-round skull, which

still characterizes the pure Turkish and Magyar blood, designates

him as belonging to a Turanian race. The last figure in the group

wears the Phrygian cap, and personifies the Lydian empire of

Croesus, of which Phrygia, on account of its rich gold-mines, was

the most important province.

Thus, in the rock-hewn tomb of Darius, (about 490 b . c.) at a time

1« Types of ManJcind, p. 85, fig. I ; and pp. 247-9.

1« Texiee , L’Arménie et la Perse, II., pl. 126, “ Persépolis—Tombeau dans le roc.”

C U N E I F O R M "WRITING. 151

when Greek art was still archaic, Persian sculpture preserved

five characteristic types of. mankind in an admirable work of art,

as evidencea of the constancy of the peculiar cast of features of

human races. The monumental negro resembles the negro of to-day;

the Arian features of king Darius and his guards are identical with

those we meet still in Persia and all over Europe; the Turanian (or

Scythian) bears a family resemblance to many Turks and Hungarians

; the identity of the Assyrian and modern Chaldean physiognomy

has been mentioned and proved above; and the Phrygian

represents the rriixed population of Asia Minor, a modification of the

Arian type by the infusion of foreign blood—Iranian, Scythic, and

Shemitish interminglings.

Persian art, as a branch and daughter of the Assyrian, never rose

to a higher development than under Darius and Xerxes. The dissensions

and the profligacy of the royal house checked the progress

of art, which remained stationary until Alexander the Macedonian

destroyed the independence of the empire, and tried to Tiellenize the

subdued Persians. His endeavors, continued by the first Seleucidse

of Syria, were not devoid of results; because, even when Persia

recovered its independence and re-appeared in history as the Parthian

empire, all its coins bear Greek inscriptions and imitations of

Grecian types. We ought not to forget, notwithstanding, that the

Parthians were probably not Persians proper, but an unartistical Turanian

tribe, held in subjection by the earlier Persians under their

Achaemenian kings, which, in its turn, revolting from the yoke, ruled

the Persians for above four centuries.

Some specimens of a peculiar style of art have been lately discovered

within the boundaries of the old Persian empire, v iz : at Pte-

rium and Nymphas. They were published by Texier;148 and it has

been suggested that they might be Median. The bas-reliefs certainly

present nothing to suggest any relation to the art of that race which

originated the cuneiform writing; nor is a perceptible affinity conspicuous

between them and the Egyptian style. Nevertheless, the

artists who chiselled them knew of the productions of Greek genius.

The breath of Hellenism has passed over them, as we perceive from

the following male [36] and female [37] heads. They are, therefore,

by many centuries posterior to the great Median empire. Still, it

would be presumptuous to attribute them to any determinate nationality,

since none of the highlands flanking Asia Minor, inhabited then

by aboriginal tribes, were ever completely hellenized; although they

were powerfully affected by the genius of Hellas, whose progress

148 Asie Mineure, Pl. 61, 78,—“ Bas-relief taillé dans le roc. L’Offrande”—et seq.