A. d . 50, had his name inscribed in Greek characters, on his coin,

now in the British Museum; hut the shape of his skull is Turanian,

and the die-sinker must have been a half-civilized and probably

half-bred Baetrian.

The series of the Arsacide coins is equally instructive, and leads

to the same result. The Macedonian conquest destroyed at once

the old Persian institutions and civilization; for, although Alexander

assumed the royal insignia and maintained the court etiquette

and provincial administration of Persia, yet both he and his courtiers

remained Greeks, and could not transform themselves into

Asiatics. His successors in Asia, the Seleucidse, were still more

averse to the old customs of the empire. They therefore removed

their residence and the capital of the empire from Babylon, which

at that time was still highly flourishing, so far west as Antioch; and

tried to introduce Greek manners and despotic centralized-eiviliza-

tion, into the provinces adjoining the seat of dominion. The out-

lying Satrapies could not long he kept in subjection: and during the

war between Antiochus Theos and Ptolemy Philadelphus of Egypt,

Arsaces the Satrap stirred up the Parthians (256 B.C.), and at the

head of his Scythian horsemen established the Parthian empire in

opposition to the Greek Seleucidse, who could not hold the country

beyond the Tigris. But Arsaces did not go back to the Achfeme-

nian institutions: he kept the Arian Persians in subjection, who from

the time of Cyrus to Alexander had been the rulers of the Empire:

his realm might easier be characterized as the revival of the Scythian

empire of Astyages. The Parthians had no indigenous art of their

own: according to Lucian, they were ou <piXoxaXoi, not friends of art,183

and they had to borrow their artisfie forms from their neighbors,

just as the Shemitic nations had done before them.

While assuming the empire, they copied the Greek language and

the Greek types of the Seleucidse

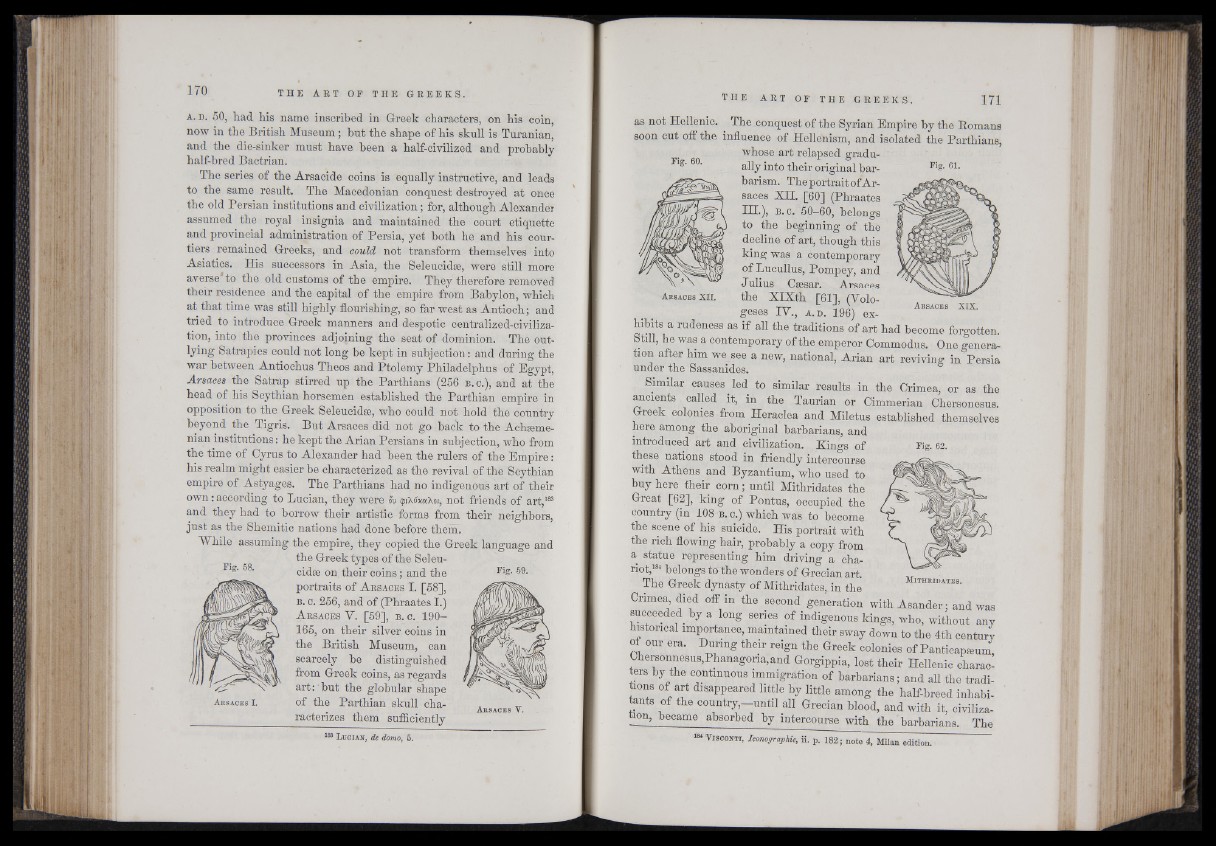

Fig. 58. Fig. 59.

on. their coins; and the

portraits of A rsaces I. [58],

b . c. 256, and of (Phraates I.)

A rsaces Y . [59], b . c. 190-

165, on their silver coins in

the British Museum, can

scarcely be distinguished

from Greek coins, as regards

art: but the globular shape

of the Parthian skull characterizes

them sufficiently

Arsaces V.

183 Lucian, de domo, 5.

,V U U t [U .G O l / v i L i l t / , / ---------------------- , - v v w I i / I i i i i m i m

soon cut off the influence of Hellenism, and isolated the Parthians,

whose art relapsed gradually

Fig. 60. Fig. 61.

into their original barbarism.

The portrait of Arsaces

XH. [60] (Phraates

Hi.), B. c. 50—60, belongs

to the beginning of the

decline of art, though this

king was a contemporary

of Lucullus, Pompey, and

J ulius Cæsar. Arsaces

the X lXth [61], (Volo-

geses IY , a . d . 196) exhibits

A rsaces XII.

a rudeness as if all the traditions of art had become forgotten.

Still, he was a contemporary of the emperor Commodus. One generation

after him we see a new, national, Arian art reviving in Persia

under the Sassanides.

Similar causes led to similar results in the Crimea, or as the

ancients called it, in the Taurian or Cimmerian Chersonesus.

Greek colonies from Heraclea and Miletus established themselves

here among the aboriginal barbarians, and

introduced art and civilization, fvi i igs of

Fig. 62.

these nations stood in friendly intercourse

with Athens and Byzantium, who used to

buy here their corn ; until Mithridates the

Great [62], king of Pontus, occupied the

country (in 108 b . c.) which was to become

the scene of his suicide. His portrait with

the rich flowing hair, probably a copy from

a statue representing him driving a chariot,

184 belongs to the wonders of Grecian art.

The Greek dynasty of Mithridates, in the

Crimea, died off m the second generation withAsander; and was

succeeded by a long series of indigenous kings, who, without any

historical importance, maintained their sway down to the 4th centurv

of our era. During their reign the Greek colonies of Panticapæum,

Chersonnesus,Phanagoria, and Gorgippia, lost their Hellenic characters

by the continuous immigration of barbarians; and all the traditions

of art disappeared little by little among the half-breed inhabitants

of the country,-until all Grecian blood, and with it, civiliza,

tion, became absorbed by intercourse with the barbarians. The

184 Visconti, Iconographie, n. p. 182; note 4, Milan edition.